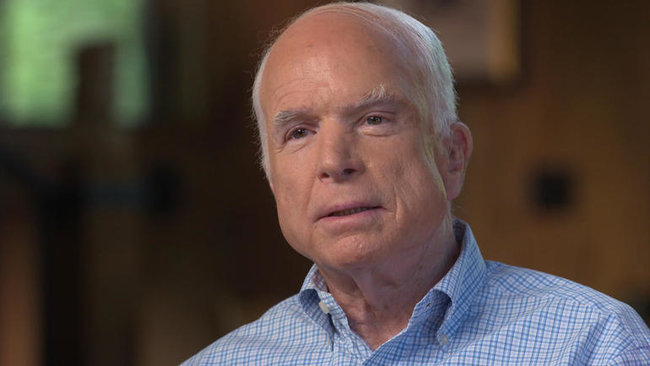

John McCain: ‘Vladimir Putin is an evil man’

In an excerpt from his new memoir, Sen. McCain discusses his longstanding opposition to the Russian strongman—and his own role in receiving ‘the Steele dossier’ about Donald Trump.

I regularly attend an annual security conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The only thing unusual about the November 2016 meeting was that it occurred just after the U.S. presidential election, and most of the formal and informal conversations among the conferees were about what to expect from the president-elect, Donald Trump.

That Saturday evening, Sir Andrew Wood, a retired British diplomat who had served as the United Kingdom’s ambassador to Russia during Vladimir Putin’s rapid ascent to the Russian presidency, asked to have a word. He told me he knew a former MI6 officer by the name of Christopher Steele, who had been commissioned to investigate connections between the Trump campaign and Russian agents as well as potentially compromising information about the president-elect that Putin allegedly possessed. Steele had prepared a report that Wood had not read and conceded was mostly raw, unverified intelligence, but that the author strongly believed merited a thorough examination by counterintelligence experts.

I was alarmed by Russian interference in the election. Any loyal American should be. I wanted to make Putin pay a steep price for it, and I worried that the incoming administration would not be so inclined. I had strongly disagreed with candidate Trump’s admiration for Vladimir Putin, which I put down to naiveté and a general lack of seriousness about Putin’s antagonism to U.S. interests and values. I was skeptical that Trump or his aides had actively cooperated with Russia’s interference. But even a remote risk that the president of the United States might be vulnerable to Russian extortion had to be investigated.

Our impromptu meeting felt charged with a strange intensity. No one wisecracked to lighten the mood. We spoke in lowered voices. The room was dimly lit, and the atmosphere was eerie. I was taken aback. They were shocking allegations.

I agreed to receive a copy of what is now referred to as "the dossier." I reviewed its contents. The allegations were disturbing, but I had no idea which if any were true. I could not independently verify any of it, and so I did what any American who cares about our nation’s security should have done. I put the dossier in my office safe, called the office of the director of the FBI, Jim Comey, and asked for a meeting. I went to see him at his earliest convenience, handed him the dossier and explained how it had come into my possession. I said I didn’t know what to make of it, and I trusted the FBI would examine it carefully and investigate its claims.

Conspiracy theories have grown around what I did and why. I’m an agent of the "deep state." I’m a double agent for Russia. I acted out of jealousy that Donald Trump was elected president. I’m faking my illness to avoid investigators. I have the same answer to inquiries from the paranoid and from the skeptical: I had an obligation to bring to the attention of appropriate officials unproven accusations I could not assess myself and which, were any of them true, would create a vulnerability to the designs of a hostile foreign power. I discharged that obligation, and I would do it again. Anyone who doesn’t like it can go to hell.

Why had I been given the dossier? That’s the first accusatory question in every budding conspiracy theory about my minor role in the controversy. The answer is too obvious for the paranoid to credit. I am known internationally to be a persistent critic of Vladimir Putin’s regime, and I have been for a long while. Wood and Steele likely assumed that my animosity to Putin ensured that I would take their concerns seriously. They assumed correctly.

Many Americans and Europeans believe that Putin changed around 2007, when he went from being a modernizing Russian leader the West could work with to a risk-taking autocrat and Russian nationalist, who resented the West, and especially the U.S. I think that’s a fallacy. At the risk of sounding self-congratulatory, I’ve been a realist about Russia and its corrupt strongman for nearly two decades. Putin and I have history, you could say, each of us having regularly made known our low opinion of the other.

I have been an equal-opportunity skeptic of four administrations’ policies toward Russia. I’ve gotten plenty of things wrong in a long political career. Putin isn’t one of them.

I made a speech on the Senate floor in 1996, after I returned from a trip alarmed by Russian attitudes, and warned of "Russian nostalgia for empire." I urged an early and rapid expansion of NATO to include the former Baltic republics and Warsaw-bloc countries, who prudently feared an imperial restoration. I, too, feared what was coming, and my pessimism was out of step with the optimism that colored most expectations for the post-Cold War U.S.-Russia relationship.

But that optimism was premised on a short view of Russian history, a view limited to Russia’s 73 years of Communist Party rule. Resentment and insecurity had been powerful drivers of Russian history for centuries. An ideological component was added for three-quarters of the 20th century, a mere blip. When the ideology failed, it was abandoned. The other pathologies are more deeply rooted.

In June 1999, after a 78-day NATO air campaign against Serbia, the government of Slobodan Milosevic agreed to withdraw its forces from Kosovo and to accept a NATO peacekeeping force there. When U.S. diplomats heard rumors that Russia would send its own peacekeeping force without coordinating its deployment with NATO, Putin (who was then serving as President Boris Yeltsin’s national security adviser) assured them that nothing of the kind was planned. That same day an armored column carrying more than 200 Russian paratroopers arrived at the airport in Pristina, Kosovo’s capital. A British peacekeeping force arrived the next day, and the ensuing standoff resulted in public divisions between NATO allies, when the British force commander refused an order from NATO’s American commander, Gen. Wes Clark, to block the runways to prevent Russian reinforcement.

Three months later, in Putin’s first weeks as prime minister, bomb explosions destroyed apartment buildings in three Russian cities, including Moscow. Putin used the incident as grounds for starting a second Chechen war and ordered the bombing of Grozny, Chechnya’s capital. The inhumanity of the Russian assault was stunning. No caution, no discrimination, no trials, brutal and merciless: Just kill people, fighters and civilians, and don’t worry about the difference.

An early and profitable Putin move to consolidate power was the understanding he reached in 2000 with the oligarchs who had made their vast fortunes from the control of privatized state assets. They were allowed to continue operating as long as they publicly supported the regime and privately shared their wealth with the ruling elite. Most of the established oligarchs went along, except for three, of whom Mikhail Khodorkovsky was the most prominent and the richest. The head of Yukos, an oil conglomerate that owned valuable Siberian oil leases, he was reputed to be Russia’s wealthiest man. He was also outspoken in his concerns about the growing authoritarianism and corruption of Putin’s government.

Khodorkovsky was arrested on trumped-up fraud charges in October 2003. His real crime was criticizing the regime and supporting opposition parties. He was given a 10-month trial in 2004-05, at which few defense witnesses were allowed to testify, convicted on all counts, and sentenced to nine years imprisonment. Two years were added to his sentence in a subsequent trial.

The West might have been appalled to see a well-regarded Russian businessman shackled and forced to endure an obvious show trial, recalling images of Soviet-style justice in the bad old days. But many Western governments continued to view Putin as a man they could do business with, literally and figuratively.

I understood the impulse for wishful thinking. The sudden end of the Cold War had left a lot of Americans, including me, giddy with optimism for what the future might hold for relations between the former superpower enemies. But at this point it was just delusional to believe that Putin would ever be our democratic partner. All that was in Putin’s soul, I said after Khodorkovsky’s arrest, "is the continuity of 400 years of Russian oppression."

That message wasn’t well received in Washington or the capitals of Europe. Hardly a month passed when the Kremlin strongman didn’t supply us with more evidence to substantiate the charge. In 2004, Putin ordered Russian security forces to storm a school in Beslan, North Ossetia, where Chechen terrorists were holding over a thousand hostages. Using tanks and rockets, the school was liberated at the cost of more than 330 innocent lives, 186 of them children. In a 2005 speech, Putin decried the dissolution of the Soviet Union as "the greatest political catastrophe of the 20th century." On Oct. 7, 2006, Putin’s birthday, courageous Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya was shot several times at point-blank range in the elevator of her apartment building. The next month the Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko lay poisoned and wasting away in a London hospital.

The Bush administration and most European governments now had a more realistic appreciation of the man in whom they had invested too much hope, and of the rapidly disappearing chances for a broadly cooperative relationship with him. But the evidence of his authoritarianism and corruption had been there all along. In an interview in 2006, I warned that "the glimmerings of democracy are very faint in Russia today," citing Putin’s repression of dissent and the Russian press. We need "to be very harsh" in response, I urged.

I was an object of occasional but pointed criticism in various organs of the Kremlin’s propaganda machine. Sometimes the complaints were from Russian government officials, lamenting my "old Cold War mentality." Often the alarm about my hawkishness was given voice by random Russian citizens, chosen for their scrupulous honesty, no doubt, and the acuity of their political insights. A retired Red Army officer earned favorable press notice by claiming to have manned the surface-to-air missile in Hanoi that had destroyed my plane. He was a modest hero, a Russian newspaper tribute to him described, who had done his duty and earned the respect of his grateful nation.

With the inauguration of the Obama administration came its vaunted reset of relations with Russia, which sought Russian cooperation on arms control and other security issues at the cost of not troubling Moscow too much over its endemic corruption, repression and intimidation of its neighbors. Sanctions imposed by the Bush administration the year before were lifted. Two missile defense sites under construction in Poland and the Czech Republic would be canceled to placate Russian objections. NATO enlargement was largely shelved.

It’s fair to recognize welcome developments the reset might have encouraged. Russia agreed to let us fly military supplies to Afghanistan through their airspace. Russia agreed to join the international sanctions regime against Iran. The administration would also credit the new START treaty to the reset. (I didn’t think that was a good deal, so I wouldn’t include this among welcome developments.) I didn’t see many other benefits to our outreach to Russia. Nor did I expect any.

Vladimir Putin is an evil man, and he is intent on evil deeds, which include the destruction of the liberal world order that the United States has led and that has brought more stability, prosperity and freedom to humankind than has ever existed in history. He is exploiting the openness of our society and the increasingly acrimonious political divisions consuming us. He wants to widen those divides and paralyze us from responding to his aggression. He meddled in one election, and he will do it again because it worked and because he has not been made to stop.

Putin’s goal isn’t to defeat a candidate or a party. He means to defeat the West.

President Trump seems to vary from refusing to believe what Putin is doing to just not caring about it. To his credit, he overturned the Obama policy and supplied lethal assistance to Ukraine. But he needs to comprehend the nature of the threat Putin poses. He needs to understand Putin’s nature, and ours.

Last year, President Trump implied that our government was morally equivalent to Putin’s regime: "We got a lot of killers—what, you think our country’s so innocent?" he told an interviewer. It was a shameful thing to say and so unaware of reality. He said it as Russian bombs fell on Aleppo hospitals, as Ukrainian soldiers defended their country from another Russian attack, as the most vile false accusations pitting Americans against Americans coursed through social media, disseminated by an army of trolls paid by Putin to destroy the fraying bonds that hold our society together.

We must fight Vladimir Putin as determinedly as he fights us. We will stop him when we stop letting our partisan and personal interests expose our national security interests, even the integrity of our democracy and the rule of law, to his predation. We will stop him when we start believing in ourselves again and when we remember that our exceptionalism hasn’t anything to do with what we are—prosperous, powerful, envied—but with who we are: a people united by ideals, not ethnicity or geography, and determined to stand by those values, not just here at home but throughout the world.

This essay is adapted from Sen. McCain’s new memoir (written with Mark Salter), "The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights and Other Appreciations," which will be published on May 22 by Simon & Schuster.

By John McCain, The Wall Street Journal