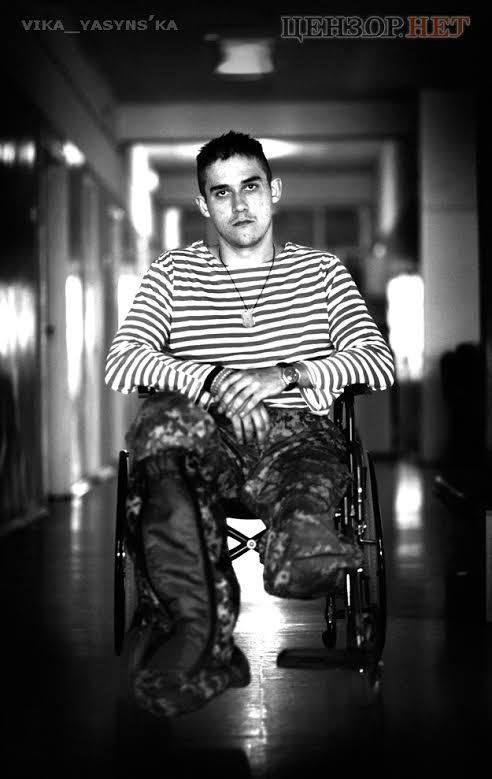

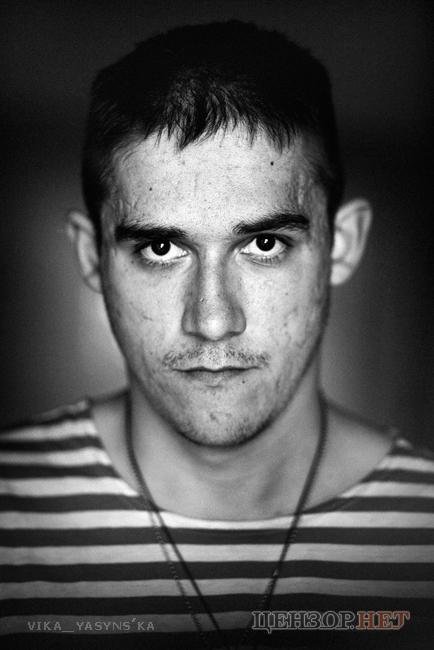

Stas Stovban, call sign Waltz: "In first year without my leg, I wore three prostheses. I broke first one when I jumped out of APC, another one was shot off"

In 2015, this paratrooper took part in fierce battles at Donetsk Airport, but even after losing his leg, he did not leave the army and continued to defend his country.

In 2022, during the first days of the full-scale offensive, he found himself in Irpin near Kyiv, and since 2023 he has been leading the "Omega" special forces group of the National Guard of Ukraine - he has mastered artillery weapons and effectively strikes the enemy across the entire front line.

There was a lot of talk about this soldier in 2015, because Stas was in that last rotation to Donetsk airport when "the concrete couldn't withstand." During the detonation of the new terminal, a floor slab fell on the paratrooper. One of his legs was amputated in Donetsk, where he and other wounded soldiers were taken by the occupiers... During our current conversation, we recalled events from almost eleven years ago. They seem like ancient history, because the war has changed its nature, pace, and scale several times. But Stas has not changed — he is a steel paratrooper who has been defending the country all this time. Since 2023, he has chosen a different format of service for himself – the "Omega" special forces unit of the National Guard of Ukraine. Stanislav is not shy about admitting that he has become extremely tired over the years, but as long as there is no other way out, he must continue what he has started. And now, together with the fighters of the group he leads, he is mastering new methods of destroying the enemy.

"Before that, we were the 6th detachment of the fire support group," explains Stas. "Now we will be the 1st special forces group. All "Omega" special forces units are primarily about intelligence. Fighting intelligently and thoughtfully is our main rule. And the UAV unit we are developing is intelligence plus."

Stas Stovban is an example of a defender of Ukraine. Tired, torn apart by wounds, but as long as there is an enemy on our land, he is ready to fight for it and for the future. He is well aware that russia has been trying to subjugate Ukraine not for four or twelve years, but for three hundred years. We also talked about this during our long but incredibly interesting conversation.

"IN THE TWO YEARS OF OUR GROUP'S EXISTENCE, WE HAVE NOT LOST A SINGLE WEAPON, AND NONE OF OUR FIGHTERS HAVE BEEN KILLED."

"I learned about 'Omega' and saw the real work of this unit in 2022," says Stas Stovban. "At that time, I was part of the airborne assault troops performing tasks to defend Irpin. It was there that I met the guys from the 1st "Omega" Special Forces Unit. I was very impressed by their work, and since I am now serving here, I understand that they feel the same way about me. At the end of 2023, I was offered a position in 'Omega,' and I accepted. I do not regret it. Objectively, in my 15 years of service, this is the best unit I have ever served in. Honestly.

- How does this excellence manifest itself?

As a group commander, I have more freedom here than I have ever had anywhere else. When I have an idea about how to best accomplish a task, I know that the command will listen to me and take my advice. Plus, and this is actually the biggest motivator for me to serve, is my group. Objectively, these are the best Cossacks I have ever worked with in my entire military career.

I was one of the first members of the 6th Special Forces Unit, serving here since the day it was formed. I recruited my own group. Different guys came. There was a normal screening process for military structures, some people took root, some didn't. Those who didn't show themselves in the best light were weeded out, the best ones stayed. This is also a plus for me as a group commander in the 6th 'Omega' unit: I can influence which people I keep, with whom I will then have to carry out tasks. That is, I can select them myself, I can submit candidates to the commander that are interesting to me, and I know that they will be lobbied for me.

- What is most important to you when selecting people? What questions do you ask, what characteristics do you pay attention to? What experience do you need?

- Experience is always good. But most of my guys came to me as "green". Okay, maybe not most, but quite a few.

- "Greens" means they didn't know anything?

- Yes. And we all learned to work together, formed a team – and it turned out to be a very good unit. As for the selection criteria... I always pay attention to moral and volitional qualities and, in general, to motivation for service. If the motivation is financial and only financial, then, as a rule, we are not on the same page. If a person has other motives, we can consider their candidacy. I have very good guys, they know why they are here, what they are doing. Therefore, I have no problems with discipline.

- A special forces unit means that a person has to be a cyborg. How can you turn someone who knew nothing, had a civilian profession, and had never seen a weapon before into a fighter?

- First of all, special forces is a very broad term. Specifically for our unit, the first thing that is required is intelligence. If a person has that, they will develop and learn. In the Omega special forces units, from the 1st to the 5th, the guys are trained for close combat, assault work. Everyone I've worked with has been absolutely decent people. The specifics of our 6th unit are slightly different. My particular area of expertise is artillery, so I selected people based on their mathematical abilities, among other things. But no matter what the training is like, no matter how many training grounds and similar things there are, a person reveals themselves, truly learns something and gains experience during combat operations. To answer your question about how long it takes to turn a rookie into a fighter, it takes a year, even a little over a year of almost continuous rotations. As a result of this course of events, we have what I call my favourite unit.

- What exactly are you proud of in your unit's work? What interesting things have you managed to do?

- I can't even count where my guys have worked. From 2023 to the present, we have been in the Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv regions, in Kupiansk and Pokrovsk... The guys even worked in Kursk region. I consider my achievement as a group commander to be the fact that during this entire period of combat missions, I have not lost a single weapon and there have been no casualties. There have been wounded guys. Unfortunately, this is war, and there's no escaping it. But there have been no casualties.

We didn't invent the wheel, but we have a rather interesting and specific concept for the use of our artillery. We work with a 105-millimetre Melara Mod 56 howitzer. Its best quality is that it is collapsible and modular. There are three points that I, as the group commander, consider essential when carrying out our tasks: we secretly move into position, we camouflage ourselves as thoroughly as possible, and we never neglect our engineering equipment. Our gun is always dug in, and we transport it only in disassembled form. And all this gives positive results.

We have a lot of hits. Our work during the first rotation in Zaporizhzhia, near Robotyne, was the most productive. That was the beginning — the end of summer 2024. That's where we hit the most important targets... But back then, the nature of the war was different than it is now. Drones were already in use, but not as actively. The Russians were advancing with large masses of infantry — groups of 10-15 people. Hit them — I don't want to. Now there are certain questions about the effectiveness of 105-millimetre artillery, because the assault groups are small, and a cannon is not a sniper rifle. Now our cannons are used as a means of suppression, to suppress the enemy with fire, to prevent them from raising their heads while an FPV drone is flying at them.

- I have heard that the first shell fired by mortar gunners or artillerymen is, so to speak, a test shot. It does not necessarily hit the target. The second and third shots are supposed to hit where they are supposed to. How important is it for you that the first shell hits the target?

- To be honest, if the first shell hits the target, it's pure coincidence. I've reached a level where it takes four or five shells to hit one target. But it's a complex issue. A lot depends on the quality of the shells themselves. But, thank God, we're fine with 105 shells, at least for now. Plus, 'Melara,' our howitzer, is a precise weapon in itself. It's an old gun that was probably used in the Vietnam War. But it was designed as a mountain gun, so it's light and mobile, which fits perfectly into the concept of a special forces unit. It allows you to maintain the speed of maneuver. Today we can work from one firing position, and in a few days from a completely different one. The gun can be disassembled, loaded onto a pickup truck, moves and works from a new position, secretly from the enemy. It is quite accurate in itself. We have made quite a few hits with the first shell, and quite a few with the second. To destroy an enemy dugout, we need four to six shots.

- After the first combat rotation, were there guys in your group who said, "No, this isn't for me. I can't overcome my fear"? Or, conversely, did anyone who didn't show themselves to be a fighter before reveal themselves during the rotation and feel at home in war?

- Most often, the one who shouts the loudest fights the least, and the one you would never think of, in a critical situation, shows such abilities, such endurance, that you wonder where it came from. In my unit, there was only one case when a person really broke down and could not continue working. It was not his fault. I have no claims against him, no comments. It just happened. Unfortunately, these things happen. We weed out such people, of course, but we allow them to continue serving in the Armed Forces.

It is impossible to predict unexpected reactions. This is another reason why I love my guys: because they all turned out to be "tough nuts". Whenever a new unit is formed, after the first combat missions, a high percentage of people drop out: some due to health reasons, some due to moral and combat qualities, and some simply because they can't cope. This is especially true in a unit like ours, where we have "starred tasks," where we have to work hard, where we have to work correctly and with our heads. But it so happened that all my Cossacks can handle the load. I won't say that they don't feel it, but they've gotten used to it and now work in these conditions perfectly normally.

My guys are very eager to work. They are ready to go anywhere to be of the greatest use. I say it's a question of motivation. People know why they are here, and they know that they didn't come here to sit around, but to work. Therefore, my task as a commander is, on the one hand, to slow down their enthusiasm a little, and on the other hand, to channel their energy in the right direction and ensure that, as far as possible, they complete all their tasks while remaining alive and healthy.

"WITH OUR TWO GUNS, WE DESTROYED SIX OR SEVEN POSITIONS OF ENEMY DRONE CREWS."

- You have extensive experience of war, dating back to 2014. Can you analyse how its nature is changing? And how has it changed over four years of full-scale offensive?

- Striking is the right word. It's striking how everything is changing. To be honest, I thought that at some point we simply wouldn't be able to keep up with this pace. Because you work on combat orders, return home, rest for two or three months and then return to the front. Well, two or three months is the ideal scenario; more often than not, it's much less. When you return, you find a completely different front. Everything you knew about combat operations before no longer works. The geometry of war is completely different. Basically, everything is now moving towards a situation where logistics will be almost impossible. We are already thinking about how to deal with this, and we have some ideas. Of course, I will not disclose them.

In 2014, and indeed before the full-scale war, there was nothing even close to this. I always recall the story when, near Horlivka, the shortest distance between our and enemy positions was 400 metres. At the same time, a 76-tonne truck could easily drive up to us, turn around, unload its cargo, the driver would drink coffee with us, and only then drive back. Of course, things are different now (smiles). And the trend is that the longer this war drags on, the faster and more dynamically the picture of this war changes. Our task is to respond to all this in a timely manner. So far, we are coping.

- I wonder, have you managed to destroy enemy pilots? Has that happened?

- We had a job to destroy pilots at their positions using artillery fire. When our reconnaissance detected the take-off point of an enemy UAV and identified that location as their position, we successfully fired at it with our cannon. Six or seven such positions were destroyed in Robotyne alone, using only our two cannons.

When you met your guys, did they immediately understand that you were missing a leg?

No. Many people still don't know about it (laughs). Well, everyone in the group knows, but probably not everyone in the unit. To be honest, it's not that big of a deal for me. Perhaps if the amputation had been above the knee, it would have been more noticeable. With the current level of prosthetics, I don't see any obstacles to my service — not at all. When someone says they won't be on duty or wants to take leave due to health reasons, I say, "Only I have the right to demand something due to health reasons!" But it's all joking. By the way, this is another strong point of our unit: we have the most trusting relationships with the members of the group. I won't be lying when I say that we live like a family. This is my second family. I really love each of my Cossacks. We can joke around regardless of rank or position and communicate sincerely.

- How old is the youngest and how old is the oldest in your group?

- The oldest is 52. He is a driver. The youngest is 22.

There is little left in the army that I have not tried. Except that I have never been an aviation pilot and have never served on a ship. I have tried everything else. Now we are actively developing work with FPV drones in our unit. This is the future, and I want to keep up with the times. My group agrees with me that we want to be useful, we want to develop and be more productive. Therefore, since the unit's staff has expanded and a new FPV group has been created, we decided that we need to jump into this niche. And now, as I see it, the guys are happiest that they are carrying less metal. Because a cannon weighs one and a half tonnes, and every time you have to disassemble it, reassemble it, carry it to the landing site... And all this while wearing body armour. No spine can withstand that. We already have 23-year-old guys with disc protrusion. There's no getting around it, these are the realities of the job. But no one has ever complained. The guys may grumble, but mostly in jest. Seriously, we do our job, we understand why we do it, whether we like it or not.

When I took the position, like the others, I learned artillery. I am self-taught. My military education is as a paratrooper officer, a tactical-level commander of airborne assault troops. I discovered artillery for myself from scratch. Because at that moment it was effective, we could be useful – and practice showed that quite significantly. Perhaps we did not fully master some of the artillery practices that professional artillerymen have, as well as traditions. But the fact is that we are getting results – and that's cool.

"ON 18 FEBRUARY 2014, I ALMOST GAVE UP MY SOUL TO GOD WHEN THE BERKUT DISPERSED A DEMONSTRATION IN MARIINSKYI PARK."

- How did it all start for you? Did you join the airborne troops before Maidan, before 2014?

- I have been serving since 2012. I don't know where my parents failed me, and I fell on my head, but for some reason, I wanted to be a soldier my whole conscious life. It was my conscious decision.

- Are there any military personnel in your family?

- No, none of them are career soldiers. My father is an electrician, my mother is a secretary. I don't know where I got it from.

- Books, films?

- Films sparked my interest, but they didn't make me want to join the military. It was quite the opposite, in fact: I watched military films because I wanted to be a soldier. I don't know where it came from, honestly. I can't answer that question myself. In 2012, I was drafted into the airborne troops, and I'm very happy about that. Even though I'm now serving in "Omega," which is also very cool, I still identify myself as a paratrooper.

- But you also participated in the events on Maidan in Kyiv...

- On 18 February, I almost gave up my soul to God when the "Berkut" riot police dispersed the demonstration in Mariinskyi Park... It was a real shock for me. I never thought it would come to that. For me, it was probably less of a shock when Russia sent troops into Crimea than what happened in Kyiv. After Maidan, I perceive everything as something that is as natural as possible. But then it was a shock.

Maidan was the beginning of a turning point. This is my point of view, but it is historically confirmed: every country goes through a period of state formation. Take America, Germany, Italy, or any other country — they all went through some kind of war or internal or external conflict. Now it's our turn. Maidan is painful for us, but it is still a starting point when we stood up and were able to say that we are a nation. We can do it. We are free. We are identical. We are not russia. For me, the most important thing is that we are not russia. Because before the events of Maidan, when I was already a soldier, during joint exercises with the Americans and British, I saw that they hardly noticed the difference between Russians and us. They saw that we had ushanka hats and badges with buckles, and it didn't even matter to them that there was a trident on the badge instead of a star. That's it, Russian – what's the difference? rasha. And now the world sees that it's not rasha. And that's very important to me. Maidan was not just for nothing — it was necessary! And it happened at just the right time, in fact. Because a little longer and it would have been too late, we would now be a second Belarus. The only thing, of course, is that it is very sad and very bitter that everything is happening with such losses, that we are paying such a high price for it. But freedom is never free.

Did you expect a full-scale offensive? That so many Russians would come in, and across the whole country?

- On a subconscious level, I did. It's not even that I expected it, I allowed for such a scenario. Even before the events of the Maidan, when I was a schoolboy. I am from western Ukraine. My great-grandfather fought in the UPA. I always knew that there were bad people living on the other side of the border. Basically, I love history, I know a lot about our relations with russia, and for me it was just a matter of time. But still, it was at the level of assumptions and accepting in my mind that hypothetically such a thing was possible. But after the turning point of the Maidan events, everything else was to be expected.

- So, did your family say that Russians were enemies? Did you know this from childhood?

- Yes. I know a lot from my grandfather, who was a member of the UPA when he was young, still a child. I know about my great-grandfather, who fought in the UPA. I know a lot about relations with Russians from my grandmother, who comes from the Chernihiv region, where they also suffered a lot at the hands of the Russians. I knew that russia was the enemy, even when it wasn't obvious to everyone else. And there were many people like me, as practice has shown.

This is an existential process that, in my opinion, began in the mid-17th century. It has continued with various changes and varying degrees of success: sometimes we regain our independence, sometimes we lose it. This has continued to this day. Now we are at another turning point, which we must survive. That is how I see it.

I think that now the centre of patriotism in Ukraine will shift to the southern and eastern regions, it will manifest itself in those people who have seen and felt this war, who have understood well what the "Russian world" is... Agree with me: the further away from the front line, the less people have a real idea of what is happening. Where do people most often block roads and shout: "The TCRs are unworthy!" and "We won't send our boys to war!"? In the western regions. I don't want to offend anyone from there — many of my brothers-in-arms are from there, and they are fighting with dignity — but that is the trend right now.

When I first came to Donbas in 2014, I discovered that the city of Donetsk is Russian-speaking, while the entire periphery, the entire rural area around it, speaks Ukrainian. At the time, I thought: wow! But how did it happen that some "Cossacks" hung Russian rags here? That's why I say: Ukrainians are everywhere. Wherever our borders are, everyone there is Ukrainian to me. It's just that some are more aware of it than others. That's all.

- Survive, yes. But win? Can we get rid of the Russians at all? Do you have an answer to that question?

- I am inclined to think so: we just can't stand it Again, this is an existential conflict, and at the end of it, either we or Russia will remain. Perhaps... Not perhaps, but probably, our Russian-Ukrainian war of the 21st century is the peak phase of this existential confrontation, the greatest in 300 years. The circumstances are such that there is nowhere else to go — either we will cease to exist, or russia will. Again, I do not expect it to disappear from the map. Perhaps it will disappear in its current form – imperial, abnormal. Then, for me, this war will be over. I do not know what I personally will consider a victory. Because, over the years that the war has been going on, I have lost so many wonderful people. I could delete half of my phone book... Even if putin died tomorrow and russia ceased to exist structurally, I would not perceive it as a victory.

- Too high a price?

- Too high a price. I can clearly define what defeat in this war means to me, but I can hardly define what victory means.

"THE DOCTOR POKED ONE LEG WITH A LARGE NEEDLE. NO REACTION. HE SAID, 'WE'LL REMOVE IT'. HE POKED THE OTHER ONE: 'WE'LL KEEP THIS ONE'.

- You were wounded...

- On 15 January 2015. I was one of the last, maybe the last, I'm not sure who was evacuated from the airport. Well, the way they evacuated us was basically like being taken prisoner. Actually, as paradoxical as it may seem, for some reason I have very warm memories of those events. I was also with some incredibly powerful people at the time! Even at the end, when we realised we were done for, we were joking and telling anecdotes. The atmosphere wasn't panicky at all. That’s what really stuck in my memory.

We drove to the airport in an MT-LB. I lay down inside with my feet towards the door. I had a machine gun with me. The guys loaded up: "Here's your BC." And they put two boxes of ammunition on my chest. We set off. They started shooting at us. The armour was rattling, and I realised that if something happened, I wouldn't even be able to open the ramp myself, I wouldn't be able to get out. I was right. When we arrived, they pulled me out of the vehicle by my legs. I was happy to be there. That was on 12 January. And on the 15th, the enemy blew up the ceiling of the terminal where we were. I was crushed by the same concrete that couldn't hold...

I remained in the terminal until the end. From there, the katsaps took me and brought me to a hospital in Donetsk. I don't remember exactly how they took me away because I was a little cold. The guys thought I had already passed away. The last thing I remember from the airport is that it was cold at night and I was slowly bleeding out. I was fading away.

I had flashes of consciousness. Yeah: the katsaps are walking around. I wanted to have a grenade with me for such a case. But it fell out. I faded out again. Then I saw the surgical light. I didn't understand where I was. I started waving my arms around. They said, 'Lyezhi' [Lie down]. Phew. So I'm lying there. Then it hit me: 'Why did they say lyezhi instead of lezhy?' That’s how I realized I wasn't among my own.

Then I remember the doctor coming in. I found out his name was Rinat Refatovich. He died of COVID. He stayed in Donetsk all those years. He poked my leg with a large needle. No reaction. He said, "We'll remove it." He poked the other one. "We'll keep this one." Because the second toe moved. And he left.

- Were both legs injured?

- Both were just hanging by the fabric of my trousers. It’s just that the artery in my left leg remained intact, and it was constricted by a tourniquet.

- So, they basically sewed the left one back on?

- Yes. It had also been crushed by a concrete slab.

Photo: Vika Yasynska

We were exchanged fairly quickly because we had been exposed. Those who remained unharmed were taken to the basement. Taras Kolodii was probably the one who spent the longest time in captivity. He was exchanged about a year and a half or even two years later. The wounded were taken to the hospital, where for some reason they began to be filmed very actively. After that, of course, we couldn't disappear. Especially since some OSCE people were driving around and saw us. So, I think that about three weeks later, they exchanged us: me, Ostap Havryliak, and Max Doroshenko. We were in the same ward. Vania Shostak, call sign Doberman, was also exchanged with us.

I was taken to Kyiv, to a military hospital. Volunteers came running to me. I didn't even know who those volunteers were at the time. They gave me some things to eat. I said, "Girls, I don't have any money." "That's okay. It's free," they replied. Well, with God's help, I soon got back on my feet.

- Was there an understanding that you were in captivity?

- There were guards around us all the time. I could only move my head. In addition to my wounded legs, my chest was completely broken. So I could hardly move, only use one hand to drink water. There was no one to mock. The guys who were with me were in about the same condition. But we were still guarded. They guarded us from our own people. Someone walked around the hospital looking for those who had been machine gunners at the airport, saying that "he will cut off their ears."

When we realised that they were definitely going to exchange us, that they had caught us on cameras and that there was some kind of resonance, Ostapchyk and I started to get a little cheeky. Ostapchyk is the person who prevented me from going crazy when they cut off my leg. After that, they brought me to the ward. I looked down and saw that my leg was gone. I thought, "No!!!" Ostapchyk looked at his severed legs and said, "Oh, cool!" He's such a cheerful man. There was this unpleasant woman there, a cleaner. She kept calling us "Banderites" and threatening us: "I'll put something in your food so you won't live to see the exchange." Ostapchyk would say: "Fine. Here, scrub here, please." And she would scrub with a mop where he pointed.

I don't think I was really in captivity. They didn't mock us. Doctors are decent people. Special thanks to the surgeons who operated on me. Many of them later left for the mainland. Yevhen Oleksiyovych, Vasyl Oleksiyovych, Tanya, the head nurse... So that we wouldn't have any phantoms, she stole some "Lyrics" and brought it to us.

- Can you name who is still a symbol of the airport for you?

- Many people whose contribution to the defence of the airport is, let's say, well known - and with which I agree. This is Redut - Oleksandr Serhiiovych, a cool man! For me, these are the guys from the 79th Airborne Brigade and the SOF who started all this movement at the airport. And we were given... I don't know if it's an honour or not, or if it just fell on our shoulders — to finish it. And I have my own important names. Vadym Demchuk, squad commander. Andriukha Hrytsan. Valik Opanasenko. The guys from the 90th battalion – they're great. I probably remember Ihor Branovytskyi the most. Andrii Shyshuk, call sign Sever. Lots of guys, lots. At that moment, I understood that I was far from being in the best situation, but with people like that, I didn't even think that something bad could happen. This situation, this atmosphere that prevailed there at that moment, is simply engraved in my memory: to give up, what you are talking about? Everything will be fine now!

"I WASN'T FAMILIAR WITH THE LEVEL OF PROSTHETICS. IT SEEMED THAT IF YOU LOST A LEG, IT WOULD BE LIKE BEING A PIRATE: THEY WOULD ATTACH A LEG FROM A STOOL TO YOU, AND YOU WOULD WALK WITH IT."

- How long did it take you to come to terms with the fact that you had lost your leg and had to get used to a prosthesis? How difficult was this for you emotionally?

- Before that, I wasn't very familiar with the level of prosthetics available in the 21st century. It seemed that if you lost a leg, it would be like being a pirate - they would attach a leg from a stool to you, and you would walk with it. When I found out that there were normal prostheses that you could even run on, all my scepticism disappeared, and I wanted to get back in ranks as soon as possible. In other words, my depression over losing my leg lasted literally a couple of days, until I found out what kinds of prostheses are available.

- Have you worn out many prostheses, excuse me?

- I can't count them. In the first year alone, I probably wore out three or four. I broke the first one because I jumped out of an APC. The second one was just poorly made, it cracked on its own. And the third one — the most interesting one — was shot off! The second time, they shot off my already missing leg! It was funny.

- Where did that happen?

- Near Horlivka in 2016. There is a funny story connected with this involving Yevhen Moisiuk, who was the commander of our brigade at the time. He came to our position. I am a sergeant, senior support soldier, and I introduced myself. "Good, well done!" The second time he came, I wasn't there because my leg had been shot off by an APC. Yevhen Heorhievych asked, "Where's Stovban?" "His leg was shot off." "What a pity for the lad..." Two weeks later, he came again, and I was already at my position. "Are you making a fool of me?! How can his leg have been shot off, and he's back on duty here two days later?" The commander couldn't understand what was going on...

"Because you're a cyborg! By the way, how do you feel about that word?"

- I really dislike all this fuss around the airport. Making concrete the last thing is not good... "The concrete couldn't hold up." Everything was fine, but the concrete, damn it, let us down...

"It's like the 'fortress of Bakhmut'.

"Exactly. The same thing. This is something we need to learn from and become better, admit where we were wrong, what we did wrong. It's a defeat from which we should have learned a lesson. But we didn't.

- So, you returned to the ranks very quickly?

- I lost my leg in January 2015, and by July of that year I was already back in the battalion. I really wanted to return to my battalion, I felt comfortable there. I really loved my unit, I loved my guys. I didn't have a family then, I had nothing to keep me here, and it was actually easier for me mentally to be in the army than to find myself in civilian life. Now, I think, I already understand, that it was the team that was probably the most motivating factor, which still works today. I would have left a long time ago because I was so tired of it all. But there are the guys, there is my group — that keeps me going. I want to see it through to the end with them. And back then, I was probably driven by the same thing — that there are cool Cossacks with whom I want to continue and do the right things.

Photo: Vika Yasynska

To be honest, the army has worn me out during the entire war, and I'm probably a little burnt out. But I stick to the idea that everyone should be in their place. I know how to fight. If, for example, I were to be placed in headquarters — with all due respect to headquarters work, good headquarters, good rear support — which is very important, I wouldn't have survived there for even a week. But I know how to fight, I find it interesting, and I have a wealth of experience in it. I know how to accomplish a task, I know what it takes to do it. I know how to lead people to accomplish a task and how to keep them alive if possible. So why shouldn't I do it? I generally hold the view that if everyone in our country did what they were good at, everything would have been great long ago.

- But the strain on your leg...

- Honestly, it's not difficult for me at all. There are certain difficulties, yes. It may rub somewhere, it may be uncomfortable somewhere. But in the broader context, there are no problems. When I got my prosthesis, I walked with a cane for half a day, then realised that I didn't really need it and walked without it. And it's not just me — it's the 21st century, and the level of prosthetics is quite high.

I had prosthetics fitted both in Ukraine and abroad, in the United States. We have a wonderful foundation here – REVIVED SOLDIERS Ukraine, and I am very grateful to them. The guys and girls showed me another side of this field of medicine. I would probably have continued to get prostheses there, but the war does not allow it. In Ukraine, the further we go, the better it gets with prostheses. Do you know when prosthetics began to develop in the United States? After the Vietnam War, when there were many wounded people. By that time, certain scientific and material resources had already been developed to meet their needs. The same thing is happening here now. There is demand, so supply appears. Wonderful foundations are opening in Ukraine. Over time, I began to treat my prosthesis like a machine: once every six months, it needs to undergo maintenance, and everything will be fine.

- Was there any doubt that you would be able to lead a special forces unit without a leg? How was this treated in "Omega" when you were taken there?

- The officer who recruited me to 'Omega' knew that I was missing a leg. He saw it back in Irpin in 2022, when we were running long distances together. At one point, I stopped to adjust my prosthesis, and he said, "Are you crazy?" It was a shock to him. When he took me to the unit, he said, "You won't get into the combat group because there are selection criteria, certain standards." I agreed, "Okay." I've just had to get in. I ended up in the special forces centre as an artillery training officer. And then, when the 6th detachment was being formed, I was approved as the group commander. I called that person and said, "Remember when you said I wouldn't be in the combat group? Well..." (laughs).

- Can you explain what "Omega" is? Why is the entire special unit called "Omega", why this particular letter?

- "Omega" is the last letter of the Greek alphabet, and it symbolises the final point: we have the last word. That's why it's "Omega". I hope that's how it will be.

- You've gone from being a paratrooper - "always first" - to "Omega" - "we have the last word".

- Yes. I gave ten years of my life and my leg to the paratroopers. But "Omega" is my best experience in the service and in the security forces in general throughout my career.

I worked in artillery. Now drone work has become available to me, and I think it's more promising. Knowing the specifics of my group and its capabilities, I can say that I will be more useful working with drones than in the artillery. I am very grateful to our 105 mm guns, but they are a bit archaic now; they have served their purpose. It is becoming increasingly difficult to use them. The potential of drones is limitless and still largely untapped. The future belongs to unmanned vehicles of all shapes, sizes and purposes. Some will fly short distances, some will strike along the front line, some will cover the infantry, some will deliver ammunition, some will evacuate the wounded... I want to be where the future is, I want to develop.

- Do you see yourself in civilian life at all? Do you have a civilian profession?

- I have a civilian education, but I have never worked in that field. I am a surveyor, so it was easier for me to learn artillery. But I have not yet had the opportunity to live and work in civilian life. Perhaps someday I will, and I really want to. But how it will be, I find it difficult to answer. I have served my entire adult life.

- In the airborne troops, they didn't like moustaches, forelocks, or gypsy earrings, as you have in your ear. When did you have all this and why? Was there a need for it?

- I got the earring (laughs) as a form of protest against one commander. He didn't like it, so I wore it. In general, I consider it a very good Ukrainian tradition. I don't see myself as a Cossack or a Zaporozhian, but it makes sense, it has a deep historical context, and I think it's a military tradition that exists regardless of what you do. You are fighting, you are a warrior — and this is your sign. This is specifically our Ukrainian ethnic sign of a warrior. And I like it.

- When did you come to this conclusion?

- Already during the full-scale war. I can't say exactly when. I just wanted to – that's all. I thought it really made sense. Some people grow beards, but I liked it this way.

- Are the commanders okay with it now? In the past, everyone in the army had the same look, everyone was shaved.

- When I started serving in 2012-2015, my commander would have shaved me off by force. Now I don't see anything undisiplined about it. If I do my job and do it right, what difference does it make how long my hair is or what kind of moustache I have? I understand why uniformity is necessary. It maintains discipline in the unit. But when you reach a level where you don't need your boss to control what you do and how long your hair should be, you just do your job, and this issue becomes secondary.

"FOR ME, THE BEST REWARD IS WHEN MY COSSACKS ARE ALIVE AND WELL"

- You definitely have the Order of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi for Donetsk Airport...

- Yes, it seems I have a third-degree one.

- "It seems I have"... You didn't receive it?

- It's hard to even say where it is now (laughs).

- And the second and first?

- No. I don't chase awards, my rank doesn't matter to me. In my group, I cultivate the idea that a commander's authority should not be based on his rank. In other words, you are my commander not because you have a higher rank and hold such a position, but because you have a little more brains. You can cover me, you can guide me in the right direction, you can stand up for me. You are a commander because you have authority, not because you simply hold that position. That's my position on everything. I'm not a careerist, I'm not greedy for awards. And in general, I'm not greedy.

- How do you encourage your guys?

- My guys get awards. Sometimes it's easier, sometimes it's harder, sometimes you have to fight for it. I guess the process took the longest for me... The guys didn't do anything spectacular, but what they did do was stay at their posts and do their job. They worked on Stelmakhivka. I don't know how my Cossacks didn't die there. They worked without sparing themselves. After that rotation, one 20-year-old lad went to hospital with kidney failure. The soldiers hardly slept, only managing to drink water once every three days. I believe that this should be recognised, so I submitted the guys for "Gold Crosses." It took a long time, but they received their awards.

For me, the best reward is when my boys are alive and well. And speaking personally, the most valuable thing for me is time. Time that I get to spend with my family.

When the full-scale war began, where were you? And why did you end up in Irpin?

When the full-scale war began, I was in a unit in Zhytomyr. I encountered the war at the 99th training centre, where I was an instructor. We ran to the armoury and received weapons. I looked at the people — they seemed normal, ready for work. We expected this, and even more. We spent the night of the 24th to the 25th in Zhytomyr, digging in and preparing. We didn't know what would happen next, then we realised that the enemy was not coming this way. We received an order from the then commander of the Airborne Assault Troops, Maksym Myrohorodskyi, call sign Mike, to form several groups to work on Hostomel and Kyiv. I had a "powerful" group of cadets. Some were experienced, having fought for several years and come to sergeant training courses, while others had only just taken the oath and had not even finished their training. There were 47 such Cossacks. The commander's task was to drive along the western ring road of Kyiv to Vyshhorod and set up three strongholds there — not just strongholds, but ambush points. Because everyone was already expecting Russian equipment to enter the city. By the way, when we were getting there, we decided not to take the Zhytomyr highway — I made that decision myself, for some reason I didn't really want to do that. We turned towards Bila Tserkva and took the Odesa highway. And it was a good decision, because we would have died there ... My intuition has always worked well, even now. I call it "soldier's luck".

We drove in, set up and deploy strongholds. I see that no tanks were advancing on us. We were hungry, so we found the 72nd Brigade. They said, "We're fighting a war here," and I said, "I have 47 rangers, and they're very tough." We all worked together for a while on the Liutizh direction. Later, the 72nd sent a tactical group to Irpin, and I went there as the senior officer. The 72nd Brigade gave me an anti-tank and machine gun unit and an armoured group – two BRDMs. With such a "beautiful" composition, I replaced the 80th Brigade. We dug in at the entrance ring to Irpin. We dug a lot, and for the first three days, the guys hated me. We dug the ground like moles. But when the first attacks came, everyone was grateful. We repelled several waves of equipment, then other forces arrived – guys from the DIU, "legionnaires", there were many TDF units – volunteer formations from the local population. This whole motley crew was on the move, boiling.

- Was it scary there?

- Not really – I would even say "not at all". I'm not bragging. That was the mood back then, you know. The initial jitters passed once you realised that the Russians could be beaten. Their most elite units would come in – and get beaten back, retreat. That was the mood back then – everyone worked together in a single burst of energy. I really believed that a week, two weeks, maybe a month or a month and a half would pass, and we would drive them out. Back then, everyone was so enthusiastic about fighting rasha that they did everything without fear, without anything. Everything was done with a smile, everything was cool.

- Do you ever feel scared?

- Of course. It can be very scary. My last horror, I would say, was the last rotation in Zaporizhzhia, when two guys were wounded. The vehicle didn't make it to its position – an FPV drone knocked it out. The guys got in touch to say they were in trouble. I understand that they're wounded, but I don't understand what condition they're in. I understand that something needs to be done, but I don't even know where it happened, only approximately. At moments like this, I am scared. But my work saves me. I understand the algorithm of my actions, I work, I call the evacuation teams, I go out myself... And that calms me down.

We are fighting a truly powerful, very strong army that surpasses us in everything except, perhaps, the will to win and drones. Therefore, the only way for us to survive as a nation, to preserve ourselves, is through consolidation. Consolidation of all segments of the population. If we stick together, work systematically towards a common goal, we will succeed. If we are like a swan, a pike and a crab, nothing will work out. Therefore, it is, of course, very important that people who are able to join the army do so; people who feel an inner need but for a number of reasons cannot be soldiers should work for the army. Even a donation of two hryvnia is not superfluous. If you do not want to or cannot fight, help others to fight. If you can, if you are strong, come, we will definitely find a place for you. In our 6th detachment, you will not be offended, you will not be abandoned, you will be remembered — your needs and the fact that you are a human being. We are now either consolidating and pulling and pushing this giant — russia — back behind its border. Or we will simply not survive as a nation. And what will happen if we do not survive as a nation, if we fall in this war, if we do not stand our ground – it will be Irpin and Bucha, Mariupol and Bakhmut, only on a national scale.

Violetta Kirtoka, Censor. NET