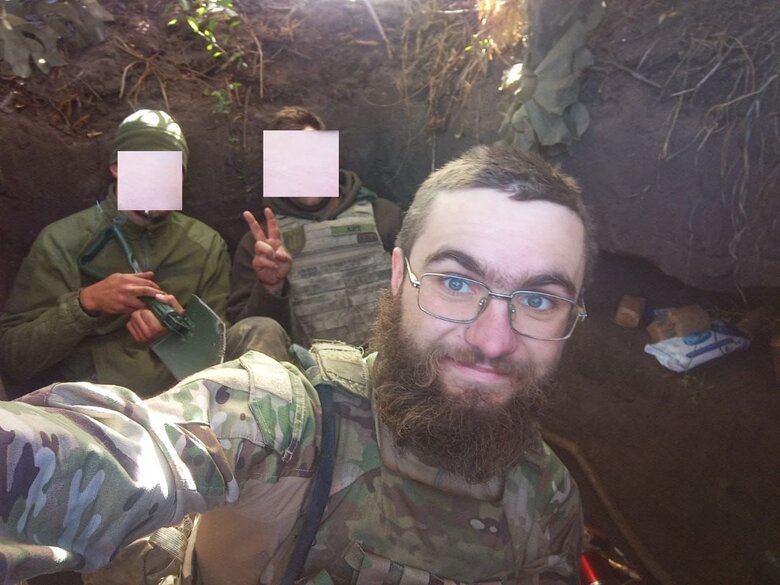

"Duel with enemy sniper? Over radio came warning: be careful, enemy has "one-eyed…" in sector" – sniper and mortar operator with call sign Chub

Before the full-scale invasion, Anton, call sign Chub, connected Kyiv residents to the Internet and in his spare time, worked at a volunteer center. When the first bombs fell on Kyiv, he went to the military enlistment office, where he was enlisted in the territorial defense. And then – three years of an extraordinary military career, where some decisions were made by Anton himself, others by the command, and from time to time, fate intervened in the course of events…

Chub is now 27, though the level-headedness and experience in his judgments would suggest he's 47. Over the past three years, he went from a rifleman to a sniper, and from a sniper to the acting commander of a mortar crew. But it all started on 24 February 2022.

- "Did you have to wait long in lines at the military enlistment office in the early days of the war?" Censor asks Anton.

- I went to the enlistment office even before the full-scale invasion started. On 23 February, when the call-up for OR-1 (the first-line operational reserve) was announced, I was already there. I came in and said: 'Take me.' But since I had no prior military service, they didn’t need me. They sent me away. The most ironic thing is that on 24 February, they were still giving priority to people with military and combat experience. So I wasn’t needed then either. But I just wanted to get in somewhere. I didn’t even expect to return home on the 24th. I thought, ‘I watered the flowers, packed the essentials — that’s it.’ On 25 February, they announced they were accepting people into the Territorial Defence. Anyone without a military ID, without service experience, the Territorial Defence welcomed us with open arms. And that’s how it all began.

- So, on the one hand, you spent two days standing in line, but on the other hand, you were enrolled in the Territorial Defence rather quickly?

- I was enrolled, yes. But even so, there weren’t enough weapons for everyone. They were still selecting people. Many were sent home. But since I already had some acquaintances there — people I’d met in line — I made my way in through the outskirts and got a weapon. We were manning checkpoints near the hospital and elsewhere.

- At the beginning, you were assigned to the infantry — the 126th Battalion of the 112th Brigade.

- Yeah. They put me down as a driver and added me to the unit roster. I’d never been behind the wheel before. But the roster had to be filled. There was a vacant driver position, so they gave it to me.

- And what happened next?

- I explained the situation. In March, when the counteroffensive near Kyiv began, they started gathering all the drivers. We were going to be deployed to Zhuliany. They assembled our company. A lieutenant colonel gathered us and said: ‘Everyone is free to go, except the drivers — you stay, you'll be in charge of transport.’ I was standing there thinking: what transport? Where? What are you even talking about? I said, ‘Sir, there’s a bit of a nuance. It’s great that you’ve listed me as a driver, but I don’t have a license and I don’t even know how to drive.’ So, eventually, we sorted it out. I was reassigned as a regular rifleman."

- Where did you have to fight as a rifleman?

- In Bilohorivka. There were sniper rifles available, and I was issued one. But since there was no designated sniper position, I remained a regular rifleman. So I had both an assault rifle and a sniper rifle — an SVD from 1984.

- So you were drawn to sniper work from the start?

- I’d picked up shooting skills back in civilian life — I practiced bullseye shooting for years. So I was already familiar with small-caliber sporting rifles before I turned 18. I knew how to aim, control my breathing, squeeze the trigger — all of that.

So when I joined the army, the first thing I wanted was to buy a rifle. The second — to join a sniper unit. In the end, I basically became an informal infantry sniper. Although I didn’t carry out any actual sniper missions. At the time, like everyone else, I pulled shifts at observation posts. I was stationed near the water pumping station in Bilohorivka. But the most interesting part came later, still in 2022.

- What exactly?

- Snipers from the 81st Brigade, the unit we were attached to, came to stay with us. They dropped off their extra gear, spent the night, and operated from our position. One day, their team leader came up to me and said: "Wanna take a walk?" I said, "Sure." He goes, "Then grab your body armor, helmet, weapon — let’s go." So we went. The mission was to adjust artillery fire and possibly reconfirm reference points. Once we crossed the front line into the grey zone, our own artillery nearly hit us. Turned out it was falling about 150–200 meters short of enemy lines. We heard the shells whistling just in time and rolled down the hill. We radioed our guys right away — they corrected their fire immediately. Then, for reasons I still can’t explain, a decision was made to continue with combat reconnaissance. We split into groups. One assault team went in from the flank to engage the enemy. Our group — a covering team plus one sniper — stayed behind to provide support. That was my first battle. October 2022. First direct contact: I saw the enemy, the enemy saw me, and we exchanged fire.

- And how did you feel?

- I didn’t feel anything. Just pure adrenaline. When I got up and started running, my legs wouldn’t work — completely tangled up. I couldn’t move properly. But during the fight itself, I was fine. Fired off a magazine case, reloaded, kept shooting. Short bursts, single shots — no wasting a large amount of ammo. I even shared rounds with a comrade-in-arms next to me — he’d fired off everything he had. So I managed to conserve some. Overall… it was fine. I wouldn’t say it was scary.

- So that first combat mission didn’t change your path as a sniper, but did it steer it?

- It steered it. I realized I wanted to be a sniper, to do this for real. From that point on, I started preparing for the role — buying the gear I needed, learning about different calibers, bullets, ballistics. I just dove into it completely.

- Without changing the unit?

- I’ll be honest — I tried. But apparently, someone somewhere isn’t happy about it, because I still haven’t managed to transfer. I’m still trying, of course, but as time goes on, it’s clear there are some complications when it comes to transferring out of Territorial Defence. It’s actually easier to bring in someone from the street than to reassign someone from TDF anywhere else.

- Your second rotation as a sniper was in the Serebrianskyi Forest, from mid-summer 2023 to January-February 24. At that stage, did you feel more prepared in sniping?

- Yeah, thanks to the instructors in Desna. They've got a solid sniper school there. Not sure what it's like now, but back then, it worked pretty well. Even though the course was shortened, they gave me the kind of knowledge that allowed me to grow. Gave me a foundation to build on. We had a clearly defined sector of our defense line, assigned exclusively to our battalion. So most of the positions I passed on my way to work were ours. I could reach out to them. That makes the job much easier when the radios are running on your own frequencies. At the very least, you can safely reach your position, not like usual.

- There was heavy fighting in the Serebrianskyi Forest back then. What do you remember most?

- Both the good and the bad. The good part was at the beginning, when we had just arrived. We still had energy, still had that drive. The enemy back then… not exactly weak, but we were facing regular units, not elite ones. They acted pretty relaxed. I could watch how they spent their day. Saw what they were doing — fixing things, building stuff, improving their living conditions. I could sit and observe them from morning till night. Not that I did it, but I could have. As for the work, it was an interesting experience. The distances were short, since it was the forest. Around 100 to 200 meters. That’s pretty close. I could hear them talking. Heard someone smoking inside a dugout. The adrenaline was intense. Any mistake could mean death.

- And what kind of mistake could that be? A branch snapping loudly underfoot?

- Yes. A branch snaps. Or a drone’s hovering — the kind you can’t even hear — and it might just turn its camera and catch your movement. One time, I took a hit to the body armor at night. I’d taken up a position, and right before the shift change, the Russians scanned all the approaches with night vision — and they spotted me under a tree. Took them a bit to pass the info to their observation post. And then — one shot from the OP (observation post), and I was off that position. I’d never rolled so fast in my life. That enemy round gave me some real motivation.

- So your body armor saved your life?

- The body armor and the rifle tripod in front of me. The bullet hit the tripod first, then my armor.

The round had lost much of its energy, so I had muscle fever for a few days and then it passed.

- Still, back then, things in the Serebrianskyi Forest weren’t that bad. When did it get worse?

- When Russia’s newly formed 25th Army showed up. They were well-equipped, trained, and started slowly pushing us back. At that point, our battalion was down to maybe one and a half companies. These were the people still going out to the positions, holding the line. And we had almost nothing to counter them with. The main problem came from our neighbors, that left our flank exposed, which made access to our positions much harder due to constant shelling and direct fire. That winter, four of our guys were killed: Chekh, Apachi, Futbol, and Dynamo. I knew two of them well — Chekh and Apachi. We started out together in March 2022. Their deaths hit me hard. It happened on the same day. The Russians didn’t spare ammo for any position. If they spotted a potential spot where Ukrainian troops might be they wiped it out. Before, I could walk through the forest and see: a hideout here, a small dugout there, a shelter. But later, when I went back in every dugout, every cover, every shelter had been destroyed. They found and flattened everything. The same happened to the position we called ‘Hrusha,’ where Chekh and Apachi were killed. Apachi died while trying to evacuate a wounded Chekh, not far from Hrusha. The guys who arrived on the same day, left on the same day. Their evacuation came under direct fire from a 120mm mortar.

Technically, if I’m not mistaken, the standard to score a direct hit on a dugout requires about 34 mortar rounds.

- Do we and they follow the same standards?

- According to the manuals — yes. In practice, of course not. We can’t afford that kind of expenditure. Those 34 rounds on our side would be split across several targets. Here, on a single small dugout. From early morning until late evening, they were pounding Hrusha. Mortar fire, FPV drones, air-dropped munitions — everything. And on top of that, they launched infantry assaults too. I didn’t personally witness the most intense phase of the fighting, but there were cases where enemy assault troops pushed forward. Even though we had support and our guys were actively firing back from the positions. These were some kind of berserkers. I don’t know what they were on — what they’d taken. But a guy gets hit with a burst from a machine gun, then stands up and keeps running. Even if a round hits your body armor, it’s hard to move after that. And yet he gets up, keeps charging, firing at our guys. These were tough fighters — well-trained. They knew what they were doing, knew where they were going, and had a strategy.

- Anton, what’s the specific nature of sniper work in the forest?

- You come to a pre-prepared position, take your shot, and get out fast. That’s it. You don’t wait around, you don’t sit there for a week like in the movies. You arrive, spot the first target, take the shot and leave. Immediately. Any delay and the enemy observation will start firing. Short distances are another factor. You need a semi-automatic weapon, no way around it. You can even use an assault rifle to stay less conspicuous. Again, short range is both a plus and a minus. The plus is, you’re unlikely to miss.

- The minus is that the enemy is at the same distance from you.

- Yes, of course. If you're a careful observer, there can be big problems.

- When you were a sniper in the Serebrianskyi Forest, what did you have to do more? Waiting for small groups of enemies, covering the assault of your troops or watching the enemy's bunker?

- The first thing is to wait for bad weather. A clear, sunny sky — that’s a problem. Ideally, it should be raining, misty — what we call bad weather in civilian life is perfect weather for a sniper. It’s a chance to approach the enemy undetected. We also operated under a free hunting mode. On my own initiative, I tried to call in mortar fire or use other support weapons, like the AGS or its American equivalent, on enemy positions. But I wasn’t very successful, since everything had to be cleared with command.

- But you were already drawn to mortars back then.

- Yeah. Mortars were drawn to me and I was drawn to them.

- Your fellow sniper, call sign Santa, told me this: "A sniper, to me, is someone who’s used to relying only on themselves, not counting on support. Personally, I feel calmer when I’m working alone. Because if I make a mistake, there’s no one else to blame but me. And I trust myself — as much as that’s possible, at least in my own head. Infantry tends to follow the herd instinct, you know? But you have to know how to take the initiative — situations can change fast." What part of that do you agree with, and where do you differ?

- I agree in principle. The only minus is that I can't work alone. After an hour and a half, two hours max, your focus drops. You just can’t stare through a scope for six hours straight — your eye gets blurry. Sure, working solo makes sense. You only rely on yourself, and any mistake is yours alone. You’ve got no one else to blame — just yourself.

But there are different situations. Someone has to be with you anyway. Unfortunately, when we were undergoing training, they tried to increase the sniper crew even to 4 people (at that time, there was a practice of groups of three). I don't know how it is now - with this large number of drones. As for me, the fewer the better. But I'm not ready to work alone yet. Of course, I have this dream of trying to work alone. But...

- But right now (jumping ahead a bit), you’re in command of a mortar crew and still identify as a sniper.

- Let’s say I’m the acting commander of a mortar team. But nothing is more permanent than something temporary. I’ve been in this position for quite a while now. Unfortunately, there’s no alternative at the moment, because a sniper team can’t consist of just one person. That’s why it’s a team. Being a sniper isn’t easy — and it’s far from cheap. It’s a costly job that takes a lot of time, learning, and preparation. It’s not just picking up a rifle and going. No. It’s a long process — and a money sink.

- I am aware of this. Back in the day, my colleagues and I raised money for a sniper unit — just to get them training ammo. They told us: there’s literally no ammo for practice, while Russian snipers right across from us have both the ammo and the opportunity. And with that kind of imbalance, who’s going to win in a duel?

- I’ve already had a duel with an enemy sniper.

- Tell us.

- It was a day with strange weather — sun, clouds, wind — and it was also our last day at that position. We were being replaced by another pair who were taking over the shift. We weren’t sure whether we should go out or not. I made a decision — we should. On the way to our hunting spot, a message came over the radio: the enemy likely had a "one-eyed" in the sector. Meaning, a drone had spotted a group escorting someone with a rifle on their back. The warning came from one of our positions: be careful. But we were already halfway there — 3.5 kilometers to go, across all the usual trails and bypass paths. We stopped at the point where we’d change into our camo. (We always moved toward the position in regular uniforms — pixel or multicam — to avoid standing out from infantry. Only as we got closer to the work site would we switch to camo, conceal the rifles, and blend in). So we’re standing there, smoking, and I go: "Do we really need this right now?" Because if a sniper’s already in position, you don’t want to be in that sector. He’ll lock in his visual references, and the moment he spots movement, he’ll shoot. Because he’ll mark visual reference points for himself and the moment he sees any movement, he’ll fire at it. If he’s already taken position — that’s it. You don’t work in that area, you don’t even lift your head. We stood there thinking — go or not go. And from our own experience, we knew: it’s better not to. But after a bit more hesitation, I said: "Look, we’ve been working this sector for nearly six months. He’s here on his first day." And we decided it might be a good idea to give it a try. Even if we don’t spot the sniper, we’ll engage whatever targets we do find. We changed our clothes, moved out. Probably sat on our spot for an hour and a half, maybe two, observing. Eventually, we got what we came for. We have a setup for recording through the scope. After I took the shot, we packed up and headed back. Later, in the dugout, we reviewed the footage, and it clearly showed someone crawling through the field with a rifle in hand, heading toward our forward position. I don’t know why he was moving in that direction, but he crawled right into open terrain. That day, we not only completed the mission, we eliminated a sniper (or his spotter). I can’t say for certain it was the sniper himself, but someone from his team definitely paid the price. An ordinary individual doesn’t crawl into an open field with an SVD. On top of that, he was in a white sniper suit. He made a mistake with his camouflage and with choosing to move through an area with almost no vegetation. He exposed himself in open terrain. That was his mistake. And that’s what got him killed.

- Anton, what’s the general attitude toward snipers in the military?

- It varies. Mostly negative. Because if you’re in the infantry and a sniper fires from near your position (or worse, from your actual position) and the enemy spots it, you can expect artillery, drones, every type of enemy firepower aimed at you. That’s how it was in 2023; probably still the case in 2024. Now, in 2025, snipers have taken more of a back seat. Drones and drone crews have moved into the spotlight. They’re the ones suffering the most from enemy firepower. Everything the enemy has — recon groups, artillery — is being used primarily against drone operators. So people have sort of forgotten about snipers for now. And with constant 24/7 surveillance, it’s much harder to take a position — or to take a shot — like we could even last year.

- Compared to last year, how much has drone activity increased where you’re deployed?

- I’m still on the same front — the Lyman direction — almost the exact same spot. The only difference is that last year, we were on the other side of the river. Now we’re on this side — because we were pushed out. Armored breakthrough — there’s not much that can stop it. If they manage to mass up vehicles and launch a push, there’s really not much you can do. The drones have changed technologically. Now they use fiber optics. I still go out into the field from time to time — just to walk. If I don’t hear anything overhead and the weather’s bad, I go out. Back when it was all wireless FPVs, I used to find them scattered around all the time. Now? All I see is fiber-optic lines. And drones with fiber optics hit their target nearly 100% of the time.

- In other words, in a matter of months, a sharp technological leap was made on both sides.

- Yes. However, the technology is actually quite old. These are literally wired drones. Electronic warfare doesn't work against them. Everything that is on the cars can practically be filmed. Okay, there are some Mavics, but you're more likely to jam your own Mavic; the enemy's is unlikely to fly close.

- Once again, briefly explain to the reader what fibre-optic drones are.

- Fiber optic cable is a type of cable that transmits signals using light. I worked with fiber optics in civilian life — I used to install internet connections for people. That thin strand — it's actually incredibly strong and thin. The only thing it doesn’t handle well is sharp 90-degree bends. It’ll break, because it’s basically made of glass inside. But in terms of tension, it’s very strong.

Fiber-optic drones can fly long distances. Their battery doesn’t waste energy on maintaining the signal — it only powers the video feed. That’s why fiber-optic drones can be used to set up ambushes and strike from far away. From a military standpoint, it’s probably a major advancement. I don’t operate drones myself, but I can feel the results of this shift to fiber optics. And it’s a real problem. For now, I don’t know of any effective countermeasures, except maybe a shotgun. I’m sure that eventually we’ll figure something out. But right now, it’s dangerous.

- During your third rotation in the Lyman direction, you also deployed as a sniper. How did the work there differ from the work in the Serebrianskyi Forest?

- In the new direction, it was all open fields and very long distances. Back then, we didn’t even have weapons suited for that range. Now we do — but at this point, I’m no longer working as a sniper. In the forest, every time I went to a "fishing spot," I came back with proof that I’d done my job. And in this area, there is a war of treelines. Life exists inside the treeline; outside, there’s nothing. Getting spotted by a drone is ridiculously easy.

- Especially when the trees are bare, no leaves, no branches, just exposed trunks.

- Mostly yes. I used to think the Serebrianskyi Forest was tough — that it was the worst. But now I miss it. Back there, I could enter the woods and disappear. Here, you can’t escape the treeline. Your movement is completely restricted. Sniper work here is basically impossible. At least when I spoke with comrades, brigade-level snipers — and they have a much wider zone of responsibility than Territorial Defense snipers — even they had very few viable positions to work from. There just weren’t any usable sectors. Now they exist, but right now, I’m not a sniper.

- I was just coming to that point. You’re now serving as the acting commander of a mortar crew. What caliber do you use? What’s the range and rate of fire?

- It’s an 82mm mortar. Maximum range is about 3.5 kilometers. Up to 3 kilometers — it’s nearly pinpoint accurate. The rate of fire depends on the situation. If it’s daytime and there’s an assault going on, we can fire pretty fast. One shot every 10 seconds — sometimes even less. That’s if we’re on a fixed position, have been firing for a while, and the mortar’s settled into the ground, doesn’t move when it fires. Otherwise, it varies. Depends on the conditions, the situation, and the gunner.

- How many people are in your mortar сre, and what are their roles?

- Three. I’m the commander — I manage the process. We use Google Meet for communication — it's the most secure option we’ve got. I get the command and pass it on to the crew. I also monitor the sky, making sure there are no drones overhead. I always keep a shotgun with me — just in case. The next person is the loader. He assists the gunner: preps the rounds, screws in the fuzes, adds the right amount of propellant based on my instructions. He gets the mortar rounds battle-ready and hands them to the gunner. The gunner aims the mortar, adjusts it based on my corrections, and fires — he drops the round into the tube.

I also orient the mortar based on the terrain. I chose the firing position, and together with the gunner, we set the angle. He and I work closely all the time. Because what might look like just a small branch to me could be a serious problem for him. He’s had an experience where a mortar round hit a branch and detonated just two meters from the tube. That’s not something he ever wants to repeat. So we actively trim trees around our positions.

- What does it feel like to constantly work with explosive ordnance? I mean, just one mortar round, if I remember correctly, contains more than two kilos of TNT.

- For the 82 we use — it’s no big deal. I already deal with a ton of explosives anyway — from FPV drones, from air-dropped munitions. If you understand how it works, it’s not that scary. The real danger comes when you get overconfident. For example, when I approach a downed enemy FPV drone, if I see the explosive is poorly assembled, I just cut it off with a knife and take it. But if I notice wires running into the drone — whether it’s set to detonate on contact or tied to the battery — then I get very careful. Sometimes I don’t touch it at all. I’ll shoot it from a distance instead... There’s nothing inherently terrifying about explosives. The key is knowing how they function. And when someone says to me, "Hey, can you get that plastic explosive out of the dugout?" I reply, "Buddy, you’re literally sleeping on 30 mortar rounds." – "No, that’s different. Plastic explosive is something else."– "Hold on. Plastic explosive burns just like TNT. To set either of them off, you need an actual explosion — a pressure wave. And if an explosion happens in here, it won’t matter if it’s the mortar rounds or the plastic explosive. Either way, they’ll zip us up in bags and send us home to our moms. So there’s no point in worrying about it

- Now you are in the room, so you have a shift. How long does a shift last in your calculation?

- The schedule is now irregular. My previous shift lasted 12 days. I was home for 4 days and now I have to go again. Because the guys who are there have switched from one position to ours - for us to go home, wash, change clothes, buy some food and come back.

- During these 4 days at home, did you mostly sleep and eat?

- Mostly yes. I also went to the city.

- Anton, have you been wounded? Or have you been spared so far?

- I’ve managed to avoid it, more or less. But I’ve started having some issues with blood pressure. When something explodes nearby — or anything loud (usually explosions) my blood pressure spikes immediately.

- What does the enemy usually hit you with? Mostly drones? Or do their mortar crews still remember you exist?

- My last outing, the one I just got back from, was pretty interesting — because the strike against us was combined. I told the guys: if they’re hitting you with heavier caliber than you’re using, that’s a kind of respect. They hit us with 152mm — because the crater went up to waist. They also used fiber-optic drones — that’s the new classic. They dropped munitions from Maviсs. And they used 120mm mortars as well. And on the very last day of our crew’s deployment, they hit us with gas. We were outside, adjusting the mortar at night. I heard the launch, the usual whistle, and the impact. But the impact was strange — it felt like the shell didn’t detonate. About six seconds later, it got hard to breathe. My eyes started watering, my nose was burning. If we had been inside a dugout and that had landed in there — I think it would’ve been really bad. But since we were out in the open, the cloud dispersed in about seven minutes, and it became more or less okay. I realized how sweet breathing can be. How good fresh air actually smells.

- What do you think it was?

- Gas. A mortar round — probably 82mm, maybe 120. Since there was no explosion, I couldn’t tell for sure. And I was a bit busy at the time. But we’d already seen gas shells back in the Serebrianskyi Forest. Even then, enemy mortars were targeting our positions with those rounds. After impact, there’s this cloud of smoke — no fire, no visible detonation. But it’s not smoke. It’s gas.

- One last question, what do you make of Trump’s proposed peace talks? Do you believe a ceasefire is possible?

- This is b*llshit, gentlemen. We fight to the end.

- Wait a minute. One thing is what you want. Another is whether you actually believe there will be a ceasefire. That’s two different questions.

- If they fall for it, if they actually sign a ceasefire... I’m not saying I’ll swim across the Tisza River or flee Ukraine some other way. But I won’t go to a second war. And there will be a second war — no question. Russians don’t forgive mistakes. They analyze, adapt, and try again. The second war will be fatal. Peace talks are great — but they’re just analysis time for Moscow.

- Their hawks say the same thing about us: that the Khokhols will regroup, build long-range missiles, even better drones, get stronger, so why are we doing this? So you think Russia will use the time more effectively?

- I’m just looking at the First and Second Chechen Wars. The first one dragged on long and bloody. The second? Quick and victorious. They learned from their mistakes back then. Unfortunately. I understand that back then, Ichkeria was under sanctions. The West believed Moscow when they said the place was full of terrorists. But Russia used that time well. And I think they’ll use it again now.

P.S. This interview was recorded on the evening of March 25. Later that same evening, after returning to his position, Anton was seriously wounded by a payload dropped from an enemy drone. "Got hit by a payload drop right at my feet." He told the author from a hospital in the Donetsk region. "Where did I get hit? Head, right shoulder blade, buttocks, right shin. Thanks to the skilled surgeons in Lyman, they’ve already pulled all the metal out. I’m on painkillers now. Fortunately, I was the only one injured. My guys are all okay. Honestly, considering the scale of the ambush and the firepower used against us — we got off very easy..."

ATTENTION! If you want to help Chub and his team, please donate here:

https://send.monobank.ua/jar/4h1pTgEZD3

Yevhen Kuzmenko, Censor.NET

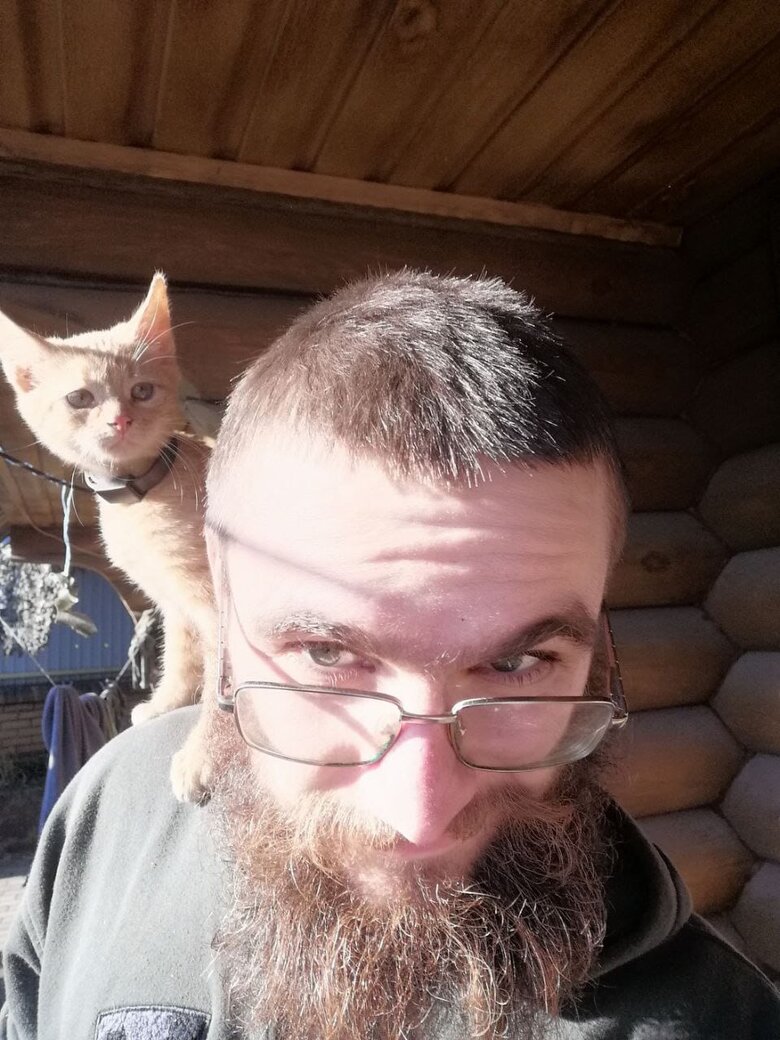

Photos and video are from the archive of Anton