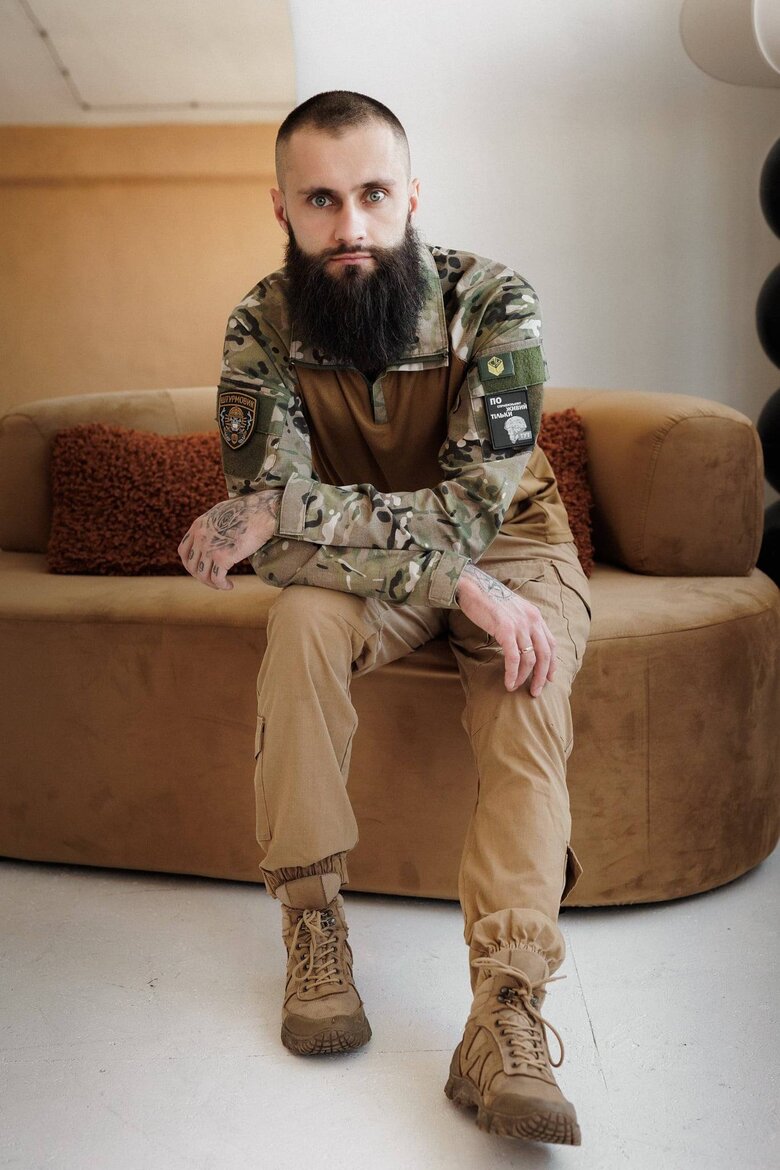

Infantryman Yevhen Skoropad: "If drone is hunting you, main thing is not to lie down and not to stay in one spot"

Yevhen Skoropad has served in the infantry for over three years. During this time, he has fought in the Kyiv, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, and Donetsk regions. He became a platoon commander. He sustained seven injuries. While he is currently undergoing treatment and rehabilitation after his most recent, fairly severe wound, we managed to speak with him about the specifics of infantry service and the myths that have emerged over the years thanks to various TikTokers.

We also spoke with the infantryman from the National Guard of Ukraine’s Spartan Brigade about how drones are affecting the course of the war—and how to survive them on the front line.

"IN BAKHMUT, WE WERE NOT AFRAID OF DRONES, BUT OF BEING AMBUSHED"

- Yevhen, how did it happen that you’re originally from Cherkasy, but at the start of the full-scale invasion, you joined a Territorial Defense unit in Irpin?

- At the time, I was living and working in Kyiv. So on the 24th, I went to the Desnianskyi District Military Enlistment Office. The line there was enormous. To avoid standing in it, I left with a few other men I met there and headed to the enlistment office in Sviatoshyn. From there, we were assigned to the Irpin Territorial Defense.

- Back then, there really were long queues and a lot of people eager to join the defense of the country. Not like today.

- One of my acquaintances stood in line for three days just to get accepted into the military.

- Before going into combat, did you have any time to prepare or learn anything or were you fighting from day one, since everything unfolded so quickly back then?

- On the way there, the guys with military experience showed us how to load a rifle, explained what kinds of ammunition there were, and how to properly fill a magazine case. And we were already fighting on February 25. But thankfully, we weren’t thrown straight into close combat. We saw the enemy from about 300 meters away in the early days. Everything developed gradually, so there was a bit of time to get over the fear and learn.

- Where did the guys get their military experience?

- Some had done compulsory service, others had fought in the ATO. One of our comrades, for example, had served in a peacekeeping mission in Iraq. He was our platoon commander. We were lucky to have him—our platoon had the fewest casualties. He knew when to flank, how to behave in combat, when it was better to wait. For instance, when the Russians were storming a tree line, he told us: one opens fire, the others wait until they come closer—then we strike again, harder, and with multiple rifles at once. In the early days, the older and more experienced guys tried not to send me to the front line. They kept me in the second row. They handed me a grenade launcher and said: 'You stay 200 meters back and cover us from there.' I regret not thinking earlier that war could come this close. I should’ve at least gone to the ATO zone for a year.

- In general, were you preparing for a full-scale war? Did you believe Russia might actually invade?

- On February 23, my friend and I were driving home from work, talking about whether a war could really start. We even made a bet—a cup of coffee. And at 5 a.m., it all began.

- Did you ever have that coffee?

- No, we haven’t seen each other since. My mom and girlfriend left the city that same day with my compadre, so I was able to go straight to the enlistment office. But my friend needed a few days to get his wife and child out, so he ended up joining another brigade in the Armed Forces. Somehow, we haven’t crossed paths once in all these years. But the main thing is that he comes back alive—we’ll have that coffee then.

- Did you join the National Guard’s Serhii Kulchytskyi Battalion after the liberation of the Kyiv region?

- Yes, in the spring of 2022. We had some time to train at a training range, and then took part in the counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region. Back then, we were positioned between Balakliia and Izium. In November, we were sent to Bakhmut.

- Do you remember what the city looked like when you arrived?

- It was alive. There was still a small market operating in the city center—we bought food there. The roads were still passable. Everything had already been shelled, but not as badly yet.

At the end of December, I transferred to another brigade that was also stationed in the city. We held the line there until March 2023.

By the time the Russians had fully crossed the Bakhmutka River, only a block and a half of residential buildings remained under the control of Ukraine’s Defense Forces. We were still there. Then we were withdrawn.

- Were there still civilians in the city?

- During the fighting, when we were in a detached house suburbs, yes. One house had us in it, another had Russians, and in between was a family—a man, a woman, and a girl, around 10 or 12 years old.

- Why didn’t people want to evacuate? Did they explain their reasons?

- Some locals cursed at us and said we were the reason the city was being destroyed. Others helped us with reconnaissance, gave us tips. As for those who refused to leave, they said it was their hometown and they didn’t want to abandon it. Different people—different views. There was one man, around 45, who constantly walked the streets. Every time he "spotted" us in a house, he’d head back—and almost immediately, that house would come under mortar fire.

- Did you respond to that in any way?

- We caught him and handed him over to HQ (headquarters) —they were supposed to transfer him to the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU). By the way, that same evening, the place where the Russians had an ammunition depot got hit. It burned brightly for almost two days. Though, maybe it was just a coincidence.

-Were there close-quarters fightings in Bakhmut?

- Yes. I saw the enemy from about five meters away—through a window, around a corner, behind a corrugated fence, when the Russians were storming our positions.

- Were they regular army troops or so-called Wagner fighters?

- There were all kinds. Some were Wagner fighters. They fought in a disciplined way and clearly knew their tactics. No unnecessary movements. There were also convicts—young, inexperienced. They wandered the city. A few times, one of them would suddenly walk into our position, into a building by mistake. It felt like they were pulled straight from prison, dumped into the city, and no one bothered to tell them what they were supposed to do. There were also well-trained soldiers. After one of the assaults we repelled, bodies were left behind—they were fully kitted out like special forces. Good thing there weren’t as many drones back then as there are now. If you saw two or three Mavics in the sky throughout the day, that was a lot. No one tried to run from them. You knew the enemy could see you and could fire a mortar or an RPG at you but you also knew that by the time they hit, you’d have already crossed the street.

- So you weren’t afraid of drones back then?

- In Bakhmut, we weren’t afraid of drones—we were afraid of walking into an ambush. A street could be loosely divided: our positions on one end, works ( a pejorative commonly used in Ukraine to refer to a Russian soldier - ed. note) on the other. And suddenly, a machine gunner could open fire from a window in one of the houses.

- Did drones significantly affect the course of the war later on?

- Absolutely. The infantry felt it the most. There are advantages but there are downsides too.

- Did you ever feel like a drone was hunting you?

I did—in Robotyne, in Lyptsi, in Zaporizhzhia. I’ve been in the infantry for three years. The only break I had was when we were withdrawn from Bakhmut for reorganization. That’s when I was offered a tactical instructor course. I thought—why sit at the command and observation post (COP) if I can go to the training ground and actually learn something?

I completed the course and became an instructor. I stayed in that role for eight months. But we still went out to frontline positions. Sometimes I was a driver, sometimes I flew drones with the guys. There were all sorts of tasks, and I had the chance to learn a lot. In particular, I learned how drones operate, what you see when one’s in the air, and what actions to take when it’s flying after you.

- What should you do if a drone is hunting you?

- If a drone is hunting you, the key is not to lie down and not to stay in one place. If you're in an open field, try to get into a tree line with more branches. Even if the enemy hasn’t been fully cleared out from that area, you still need to find trees and keep moving between them. And listen to the drone. When it starts closing in, make a dash in the opposite direction. If an FPV drone sees you, you’re its target. If you just lie down or crouch in a shallow trench, the drone operator can steer it right in there and it will calmly fly straight at you.

- Where should you go, and for how long?

- If you're walking from point A to point B and a drone follows you, turn around and go towards point A. Because you've already walked that route, you know that everyone is there, there is no ambush.

-So the goal is to avoid running into the enemy and try to save yourself?

-If a drone is coming after you, there’s a 70% chance you’ll be a 'WIA' (Wounded in action). But if you do everything right, you’ll be a light WIA. And in a few weeks, you might be back with your unit.

- You said you should move toward your own lines to avoid ambushes. But how do you do that without revealing friendly positions to the enemy?

- That’s what I’m saying—you don’t go into any positions. If you see a dugout where your drone operators or artillery guys are, don’t go near it. Just try to lead the drone through the tree line so it gets caught in the branches. When it catches on a branch, it goes down.

We had a case like that in Lyptsi. We were carrying the body of a fallen comrade out of the forest. We were walking along the edge, with a field next to us. Suddenly, an enemy FPV drone flew in from the field. We started heading into the woods, and it hit some weeds in the field and exploded. That happened maybe 20 meters from us.

If the drone gets caught in branches, trees, or bushes, it either explodes or crashes. And then you can keep moving.

Let me say it again: don’t sit down and don’t lie down. Not even under a tree. A drone operator can see that a person went under a tree and didn’t come out—and he’ll strike the tree, and the shrapnel will still hit you.

- But walking for hours is tough—people get tired.

- A drone can’t stay in the air for hours either. For example, if I see a 7-inch drone flying, I know its battery lasts about 40 minutes. But it already took at least 20 minutes to reach me, so I’ve got another 20 minutes of running left. Or if a 12-inch drone is flying, I know I’m not its target out in the open. It’s looking for vehicles or dugouts. So I just keep walking and 'listen' to the sky to figure out which way it’s heading. And if I get the chance, I'll pass the info over the radio.

- Can drones be identified visually, or does that require special training?

- FPV drones and Mavics sound different. And they fly differently. An FPV drone doesn’t fly at 50–100 meters. When I hear one in the sky, I immediately start looking for it. If I see it flying at an altitude of 30–40 meters, I know it’s not after me. It’s targeting something specific—we’re not of interest. But if it’s hunting one of us, it flies at 10–15 meters. That’s when we start taking action. You can hear and see an FPV drone. But a Mavic dropping munitions is hard to hear. And if the operator is skilled, they can fly it at 50–70 meters and drop a munition right on you. That’s a nasty thing. A lot of injuries come from those munition drops.

- I’ve spoken with guys who got hit in the trench and lost limbs.

- If we don’t fortify our positions, we understand that sooner or later we’ll get hit. 2024 has shown that the Ukrainian army has started to change in that regard—trenches are now being covered with netting, sheets of material, and so on. Back in 2023, the thinking was: if you don’t cover the trench, the enemy won’t spot you, since there were fewer drones then. Now it’s the opposite—you have to cover and fortify your trenches in a way that an FPV drone gets tangled in the netting. And if it detonates, it does so at a certain height, giving you time to get away. Same goes for munition drops. You have to cover your trenches and stop worrying about whether the enemy will figure out where you are. They’ll find out sooner or later anyway, because the sky is full of drones now. And if your trench is covered, your chances of staying alive are much higher than if a drone hits you directly.

- How important is it for an infantryman to understand drones?

- There’s a lot an infantryman needs to know. When I was an instructor, or later as a platoon commander training my guys, I always told them: "The more you know and understand, the higher your chances of staying alive." And that applies not just to drones. Same goes for mortars or any other weapon. You can figure out how many seconds you’ve got to dash to another position, or which direction the enemy is adjusting their artillery fire from. Nowadays, thank God, we live in a time when there’s plenty of useful information on YouTube: videos about different weapons. If your instructor didn’t have time to teach you everything at the training ground, you can learn it yourself there. The more an infantryman knows, the easier it is for him on the front line. Though, of course, sooner or later, you might still end up being a WIA.

- Are you a fatalist?

- This is my seventh injury in three years. Luck’s been on my side so far. Many of the guys haven’t been as fortunate.

"I HOPE FOR NEGOTIATIONS, BUT I UNDERSTAND THAT WE WILL BE IN THE TRENCH FOR A LONG TIME"

- How did you get your most recent injury?

- I went out on an assault. We were sent to the Zaporizhzhia direction. At 4 a.m., we reached a position held by our infantry. As it started getting light, we moved forward. The trench line ran through a tree line. It had been ours, then the enemy took it and held it for about a month. In that time, the Russians rigged it with tripwires. I was in front and hit one of them—it exploded. The guys applied a tourniquet on me and dragged me to the nearest position. I packed the wound myself and waited there while the others finished the assault. Then came the hospitals—first in Zaporizhzhia, then Kyiv, now I’m in Ternopil.

- I read in one of your interviews that your femur was injured.

- Yes, a metal washer hit it, and the bone cracked. Apparently, the explosive device was improvised.

In Zaporizhzhia, the doctors fitted me with an Ilizarov apparatus to stabilize it. It was removed after a month and a half.

Right now, I’m on a 30-day leave — I need to undergo a military medical commission, but the bone hasn’t healed yet. It takes about six months for that.

- How did you endure such excruciating pain and even manage to treat yourself?

- When I was packing the wound, it hurt so bad I had tears in my eyes. But I knew that if I didn’t treat myself properly, I’d bleed out or lose the leg.

And the evacuation part was "fun" too. The pickup couldn’t reach us, so they brought an ATV with a trailer. My comrade, who had a bad arm wound, and I both jumped in. Then we spent about half an hour bouncing over potholes in that thing. We were crying, laughing, and screaming...

- You’ve seen a lot of action over these three years. Something to tell your kids someday?

- Children definitely do not need this.

- So you’re not going to talk to your children about the war at all?

- I will, but I definitely don’t want to tell them everything I’ve seen. That’s exactly why I’m fighting — so my child doesn’t have to know how terrifying it is when, for three years, you live thinking each position might be your last, and each day might be your final one.

- And if you had the chance to share just one story from the war, what would it be?

- A lot has happened over these three years — it’s hard to pick just one story off the top of my head. But I guess what stuck with me the most was Bakhmut.

There were twelve of us in one building, and the Russians launched an assault.

We were on the side of the Bakhmutka River they had already taken control of. They’d destroyed almost all the houses around us and had us nearly surrounded.

They stormed, and we held our ground inside that building. We fought them off for more than eight hours.

- Couldn't they provide you with any support?

- An adjacent unit tried to send backup, and so did our brigade. But the group couldn’t reach us.

- How did it all end?

- After eight hours, we realized we were running low on ammo and grenades, and everyone was exhausted. But no one even considered surrendering, so we decided we had to get out somehow. Not all of us made it out, unfortunately.

No one could tell exactly how many Russians there were, because the moment you ran up to the corner and started firing in their direction, they’d fire back and throw grenades under that cover. But there were definitely no fewer of them than us.

- Tell me, Yevhen, in these three years, haven’t you ever considered transferring to another unit — say, becoming a UAV operator or an instructor? Infantry is the toughest branch, after all.

- I had the opportunity, but not the desire. Maybe I’m not super experienced, but I’ve still got more experience than someone who’s just in their first month of combat. I’d rather help them. I like what I do.

People need to be encouraged to stay positive, not to think that infantry is just death and misery. There’s a lot of good in it too.

- There’s a common stereotype that infantry service is terrifying and thankless. That’s why many are afraid to join.

- That's because there are plenty of TikTokers constantly spreading negativity. They’ll say things like: "I got injured, but they’re paying me only 500 hryvnias." And nobody asks why. Nor does he explain that he was removed from active duty. But nobody gets removed without reason—you’d have to commit a crime or break the rules for that to happen. There are some who run away from their position on the very first day and then start posting videos complaining how terrible army life is or how they're not being provided with something. That’s just not true. Infantrymen are supplied with everything they need. If there were fewer "video experts," people’s perceptions would change. Sure, army life isn’t easy, and there are problems, but protecting our country is our choice. I advise people to talk to those who are actually fighting, not to those who ran away or are hiding from mobilization.

- How is your treatment and recovery going now?

- It’s going fine. Unfortunately, in Zaporizhzhia, they installed the Ilizarov apparatus in a way that went through the knee joint, so now it doesn’t bend properly. But I try to see the upside—means I’ll be recovering even longer (smiles – ed.).

- The rehabilitation system in Interior Ministry facilities is now scaling up—they’re opening swimming pools. How would you assess what’s being done for wounded soldiers overall?

- A wound isn’t death—we keep living. And the conditions being provided are decent. When you’re recovering in a hospital, you can’t just lie in bed all day—you need to move. The social services work well. A few times a week, aside from medical procedures, there are opportunities to go to the theater or the cinema. Some guys say no, but I think—why not? Even if it’s just for a short time, you get to live a life outside the front line. And if you’ve walked a bit, that means you’ve worked your muscles. There’s a guy in the hospital with me who lost a leg. But he’s trying, too—he moves around instead of lying down all day. And after three months, he’s already on a prosthetic. He comes with us to the theater.

- Do you plan to return to service?

- I hope for negotiations, but I understand we’ll still be in the trenches for a long time. Even if there’s a ceasefire, we’ll likely serve on the demarcation line for a year or two. And going forward, the country will still need a strong army.

- Are you ready to hold positions even after a ceasefire?

- As long as there are no missile or drone strikes, and no brothers-in-arms or civilians are killed. If needed, I’ll serve for another year or three. If only no one had to die.

Tetiana Bodnia, Censor.NET

Photo courtesy of Yevhen Skoropad