People’s Hero of Ukraine, Sniper Andrii Lahutin: "I took out between 15 and 20 katsaps in Moshchun on February 27"

After a missile hit the neighboring building, the man ran to help the wounded, despite having shrapnel-induced lacerations on his legs. Andrii now has nowhere to live. His savings and a foreign passport with a U.S. visa were blown out of the damaged apartment. But what matters most is that he survived.

Andrii cracked a few jokes while showing me his apartment in a building right next to the one hit by a missile early in the morning on April 24. But after our conversation, he remarked: "None of this is actually funny." And it’s easy to see why. His jokes and smile toward the neighbors in the yard, his active communication in English with the numerous foreign delegations visiting the site where 12 civilians were killed in the capital, and his detailed account of that day — all of this is a form of psychological defense and a way to process what has happened. Just a few hours after the strike, Andrii’s friend posted a video from the shattered apartment: the owner standing in the middle of the wreckage, trying to make sense of what was left intact.

"I CARRIED MY NEIGHBOUR FROM THE FIRST FLOOR, WHO HAD MULTIPLE LACERATIONS AND A TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY, TO THE DOCTORS"

- "My apartment is on the fourth floor — see, both windows are now boarded up with plywood," says Andrii Lahutin, standing at the entrance to the building. "One side of my balcony was a small workshop — I had a milling machine there. After the missile strike, it ended up in the middle of the room. The other side was something of a home office. Unfortunately, I lost many valuable and sentimental documents stored there. The hard drives containing my underwater films and photo archive were smashed."

Our building was originally constructed at the initiative of Oleh Kostiantynovych Antonov. His private residence used to stand just a bit farther down the street. This place was home to leading designers and engineers from the Antonov plant.

- How did you end up living here?

- Well, both my mother and father were senior designers at the Antonov plant. And I worked there too — spent ten years at the same place. I’ve lived in this building my whole life. You could say it’s my PDS — permanent duty station," Andrii says with a smile.

- Were you home when it happened?

- Yes. I was sleeping in the far room. When the air raid siren went off, I looked around — I always keep the windows open. I heard the first impact. It landed somewhere farther away. I checked the window — nothing nearby. Then the next one hit us directly.

I was immediately pinned down by the wall that separated our apartment from the neighbors’. My legs were trapped. A window frame flew past me and shattered — I was lucky it didn’t hit me. It was dark. Dust everywhere. I crawled out of the room by feel. I usually hang my clothes on a chair. I don’t remember if the pants were on that chair or if I found them in another room. I put them on — I always keep my documents in the pockets. Made it to the hallway, found my shoes, put them on. Then found my jacket. Found my combat backpack, took out the first-aid kit. Neighbors started screaming, calling for help. I ran through the apartments. Heard cries coming from downstairs — a young guy had taken shrapnel to the neck. We pulled him out, but the medics couldn’t save him… He died. On the first floor, Aunt Nadiia had deep lacerations and a traumatic brain injury. I carried her out to the street, where the ambulances were already parked, and handed her over to the medics. Her son, Oleh, is blind. While I was helping her, someone else had already led him to safety.

- Did you check yourself for injuries?

- I suffered light lacerations on the legs, but nothing serious. I called my buddy, Sashko Myronchuk — he once pulled me out wounded in Moshchun. Sashko’s from Horenka. Solid guy, someone you can count on. And you know, my place was full of ammo and weapons — sniper rifle, scope, service pistol... Combat and sport firearms. We had to get everything out and move it somewhere safe.

- You mentioned your car was damaged too…

- My Toyota was parked in the courtyard, closer to Building No. 5 — that’s where the missile hit. When I came outside, I saw it near my entrance — the blast wave had thrown it there, and a tree had come down on top of it. Some friends have already taken it. We agreed they'd strip it for parts — whatever can still be used will go toward repairing military vehicles.

- What else of value did you lose?

- My foreign passport with a U.S. visa flew off in a direction I still don’t know. I had some cash — around $1,500 in foreign currency. That disappeared too. Though I did find €50 three days later, the passport, unfortunately, is gone. I’ll have to get a new one.

My father spent his whole life building wooden scale models of WWII fighter planes. These were handcrafted, one-of-a-kind pieces. The collection was on display in one of the rooms. It got blown apart — smashed, broken, destroyed.

I’ve probably won over 500 sports awards. I’ve been doing underwater hunting, diving, and spearfishing my whole life. I also had skiing, waterskiing, and shooting medals. Most of my awards are kept at the club, but the most precious ones were here, at home. My very first medal. Medals from the Soviet Union championships. A set of gold medals from international competitions — real gold. I also had a few valuable keepsakes. Amazingly, I found one today — a beautiful golden keychain, must weigh around 60 grams. I also recovered two gold medals. They were buried under rubbish and broken glass. I had some stunning silver and bronze medals from the championships in Syracuse — only one bronze medal turned up. The others were one of a kind…

There were also lots of small items related to my diving gear on the balcony — things I’d been collecting for years. I used to design underwater spearguns. Some spare parts were there too... All of that is gone.

When later examining the aftermath of the damage, I couldn’t figure out how I even got out of the room I’d been sleeping in. Furniture, chunks of the wall, the window — all of it blocked the way. Somehow, I crawled out through a small hole.

This is a completely civilian neighborhood — people call it the Aviatown district. The stadium across from our buildings is part of a sports complex that Oleh Kostiantynovych Antonov personally looked after. He was an avid tennis player himself. The indoor tennis hall — now with almost no windows left — was also his initiative. It was common for the children of factory workers to eventually work at the aviation plant too. That’s why Oleh Kostiantynovych knew every employee by name. He paid close attention to people and cared about them — everyone used to call him ‘Tiatia’ (daddy - ed.note) behind his back. That’s why everyone knows each other," Andrii confirms this, greeting nearly everyone on the street as we walk from the building to the stadium. Things changed over the last 15 years. The plant was being dismantled. People had to look for other jobs, left the country, sold their apartments… But still, most of us know one another and say hello. These are civilians. There’s no military target here, no logic in hitting this place. I joke now that they tried to kill me for twelve years at the front — didn’t work. So they spent another five million dollars trying to get me in Kyiv...

The video was recorded by Andrii’s friend who came to help him. It clearly shows the state of the apartment just a couple of hours after the missile strike — and his car, crushed by a tree, seen from above... Most importantly, Andrii hasn’t lost his spirit or his sense of humor.

- Did you stay near the building the whole day?

- I went through my stairwell again, asked if anyone needed help. No one did. So I packed up my diving gear and a few other things and took it all to a nearby sports club where some friends were. It was already starting to get light.

- Where are you staying now?

"The state says it’ll provide some money for temporary housing. For now, I’ve got my trailer. I bought it back during the war — for when I wasn’t staying at my PDS. It’s parked at a friend’s place by the river. I’ll move in there for now.

This video was recorded by Andrii in the afternoon of April 24, from inside his shattered apartment.

- Where did you spend the nights after the strike?

- Some friends of mine live nearby. They’ve got a big apartment. They said, ‘Here’s a room for you.’ So that’s where I’ve been staying for now.

Andrii’s apartment is now as cleaned up as it can be — all the broken pieces have been swept away and removed, the windows boarded up. The surviving kitchen cabinet fronts are covered in tiny scratches — from shards of glass. The bathtub now stands in the hallway — no walls, no doors. The toilet is "open" too. The washing machine is missing its front glass. The sliding closet doors are bent out of shape. The lamp covers, miraculously still intact, are lying on the floor. On the same shelves where his father’s model airplanes used to stand, there are now just two books: a collection of poems by Hlib Babich, a fallen poet, and stories about the soldiers of the 1st Assault Brigade.

- I knew Hlib Babich personally," Andrii Lahutin explains. "We were friends. Back when I was a volunteer, I supported a number of brigades where my friends, acquaintances, and even former students served. After my first injury, Hlib and I ended up in the same hospital in Sievierodonetsk...

We step out of Andrii’s building. Foreign delegations walk past the completely destroyed apartment block. A minister from Luxembourg approaches a group of volunteers from Norway. Without hesitation, Andrii switches to English, explaining everything the European guests want to know. Then we move on.

- Was the silver order "People's Hero of Ukraine" lost?

- It’s on my dress uniform. It’s safe. And here’s another award that means a lot to me," Andrii shows me a photo on his phone. "See the red-and-black ribbon? That’s a Finnish sniper’s award from the Winter War. And it was given to me by his grandson. He told me his grandfather received it for fighting the katsaps. Matio handed it to me and said, ‘I want you to wear it.’ The ring next to the medal was made by his grandfather from a piece of a downed Soviet plane. That survived too. After Matio gave me the medal, I was shaking for a day. That’s how much it meant to me. It’s a kind of continuity between generations.

RUSSIAN MILITARY CONVOY SPOTTED NEAR HOSTOMEL. IF WE HAD OPENED FIRE, NONE OF US WOULD HAVE MADE IT OUT

- How did you experience the start of the full-scale invasion?

- Now we can talk about it. From 2016 to 2020, I was officially recognized as the best sniper in the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the best commander of the best sniper platoon in the AFU (Armed Forces of Ukraine). I served in the 54th Brigade at the time.In 2020, during a single deployment, our platoon inflicted 12% of the total enemy losses recorded by the Armed Forces. The unit delivered outstanding results — and so did I personally. For example, there was one very important shot I made — but the award for it went to someone else entirely. Snipers are often left out of the picture in this war. It all depends on the attitude of a particular commander toward each individual... But that’s a separate story.

I left the army in 2020. I had plans to compete in the World Spearfishing Championship. It’s a pity — I was in excellent shape, fully prepared. When I started thinking about going back to my unit, we found out my wife was pregnant. We had really wanted a child. So we agreed I’d stay home a bit longer. From November 2021, I already understood we needed to prepare — the katsaps were clearly getting ready. My friends and I were analyzing the situation. The northern direction wasn’t anticipated. It had received the least attention in our planning. The four main expected axes were Mariupol, Volnovakha, Kharkiv, and Sumy. We were expecting the invasion to begin on February 16. When nothing happened that day, I even felt a bit relieved — thought I’d take my younger son skiing. And that’s what we did.

On the 22nd, I got a text message ordering me to be in Kyiv on the 23rd. I left from Slavske and got home that evening. At the time, my brigade was stationed in Marinka. But by the 24th, it was clear there was no point going to the enlistment office — we had to defend Kyiv. All forces were redirected to protect the capital. At that point, Liuda was seven months pregnant. I called a few generals I knew, but understandably, everyone was busy — I’m pretty sure their phones were glowing bright orange by then... So I called Liosha Arestovych — we’ve known each other a long time and worked closely together during that period. Then I called the 72nd Brigade and headed over to the battalion commander — his call sign is Sheriff. The unit had just taken up position in Vyshhorod. I explained how to block all access routes — both over the dam and along the main road. Spent the whole night setting up positions — a spot for a tank, sniper nests. By the morning of the 25th, they brought in a tank. I positioned it. Later that day, the infantry arrived. I called Vlad Naliazhnyi, the brigade’s deputy commander. He was happy to hear from me and said, ‘Get over to me in Pushcha-Vodytsia.’ My partner and I were ready to go — we already had weapons, even captured ones. Naliazhnyi told me, ‘Handle Moshchun.

Photo: The photo was taken in Moshchun, near Kyiv, in early March 2022. Andrii is pictured with his friend Oleksandr, who later pulled him out after he was wounded.

Just east of Moshchun was a skete run by Father Amvrosii — an old friend of mine. I used to visit him often. We used to train in knife fighting. On February 27, we arrived in Moshchun. The guys had just started digging trenches. We planned the defense line together. Then we drove back to the skete. On our way back, we spotted a infantry fighting vehicle (IFV), a command and staff vehicle (CSV), and three airborne assault vehicles (AAVs) that had crossed the river to our side of the field. I told the guys: ‘Looks like they’re about to open fire on us.’ On the right — an open field with enemy armor. On the left — a ditch and a forest. It was about a kilometer to the nearest houses. We were right out in the open, light-colored car against a dark forest backdrop. I said: ‘If they start shooting, we’ll have to break through — you jump out.’ And then they opened fire. I slowed down, the guys rolled out, and I took off. I spotted a trail over the ditch and jumped it into the forest. Once I was out of sight of enemy, I stopped, pulled out my rifles and ammo. A few moments later, the guys caught up, out of breath. I usually carry 30 rounds on me — in magazine chargers and gazyrs. I had more on me that day. I sat down and opened fire on the vehicles. From a single position, without moving, I fired 40 rounds from a distance of 700 meters. Ten days before the invasion, I had bought an expensive thermal scope — the Archer, best in the world. Thanks to it, I was able to work effectively in Moshchun: I wasn’t aiming at the vehicles but at the commanders and driver-mechanics, who were clearly visible through the scope.

The enemy was advancing in groups of five vehicles — about thirty in total. At that point, the dam in Moshchun hadn’t been blown up yet. I kept changing positions. I ran behind a pile of broken bricks that lay beyond the summer homes, closer to enemy lines. It was practically open ground, but from there I had a clear view of all the access points. Two of our guys ran off to blow up the dam — they got within 30 meters when the Russian column suddenly turned back. So I started shooting at the commanders’ backs — I couldn’t see the drivers anymore. It worked out very well. The vehicles were driving up onto the small dam — each one would rise, drop onto the embankment, and pause just for a second. That second was all I needed. At that range, a bullet takes about 0.8 seconds to reach the target. As they were retreating, I took out the commanders in at least three vehicles — I know that because they later pulled the bodies out. I think I took out between 15 and 20 of them that day. I fired 40 rounds from one position, and 35 from another. Then they pulled back. One of our guys asked, ‘What’s that vehicle over there? I look — there’s a CSV behind the bushes.

I didn’t see anyone inside. ‘Go check it out,’ I said, ‘I’ll cover you.’ They crawled up — no one there. But there was blood. We stripped a bunch of stuff from that vehicle — took documents, equipment. Then we tossed a grenade inside, just to make sure it wouldn’t be going anywhere. I reported to Naliazhnyi. He gave me more tasks. One of them was the simplest: get Ukrainian flags. None of our vehicles had identification marks. So I drove to the Epicentr store in Borshchahivka and found some flags there. Another urgent task — find a tank driver-mechanic. And I happened to know one in Kyiv. He just needed to get permission from his wife…

- Was your wife still in Kyiv at that point?

- Yes. This was March 1. That day, Naliazhnyi told me, ‘Looks like we won’t be able to hold the line. We’re short on people and ammunition. It could collapse. Staying at home is no longer an option. Start looking for houses to base out of — for guerrilla operations. That same day, I sent my wife and her mother west — first across Ukraine, then abroad. She gave birth to our daughter, Solomiia, in Munich in May. They’re still in Germany. On one hand, it’s hard — it’s painful that they’re so far away. But on the other hand… When I got pinned under the neighbor’s wall, my first thought was about my wife and daughter — thank God they weren’t in the apartment at the time. But let’s get back to what happened in 2022…

…In the evening of the 4th, I arrived in Moshchun. Saw some guys in fancy gear with weapons — clearly DIU (Defence Intelligence of Ukraine). They said they were planning a reconnaissance mission across the river. I told them everything I knew — I’d already scouted the area. We crossed over together, near Father Amvrosii’s place, passed through Rakove, and near Hostomel we saw a massive Russian column. A really long one. If we’d opened fire, we wouldn’t have made it out. On the way back, we checked a nearby farm — it was empty. Then we returned to Amvrosii’s place, got some sleep, and headed back to Moshchun in the morning. Once there, I briefed the infantry again — told them to make paths between the houses for maneuvering. If that was done right, no one would be able to dislodge us. Suddenly, someone runs up: ‘Tanks up ahead!’ I was surprised — thought there weren’t any. ‘They’re right there,’ the guy says. I ran along the street — sure enough, three tanks were positioned on a slope beyond Irpin. Three tanks and a IFV. I told, ‘Alright guys, it’s gonna be a slugfest.’ I realized the same column we’d seen the day before had crossed over. I warned the infantry: ‘Get ready — it’s about to get fun.’ I called Naliazhnyi to update him on the situation. He said, ‘I don’t need you here right now — go get some rest. I’ll need you tonight.’ So I went to get some sleep.

Thinking back to those days, I have to hand it to Vlad Naliazhnyi. There was a huge table in the command post — must’ve been six meters long. Phones and tablets were spread out on the map, and he moved among them like a pianist, tapping and swiping everything at once, chugging coffee and showing me his subordinates’ results: ‘Look how we hit them here…’ Of course, the National Guard was involved too, as well as DIU and special forces…"

Sasha and I managed to stop by my place. Got a quick shower and a bite to eat. Then my friend Vovochka — he’s with DIU — called: ‘You got a thermal scope?’ — ‘Yeah.’ — ‘Then get over here, fast. A group just passed through Moshchun.

We arrived when it was already pitch dark. In the far-right corner of the village, a house was on fire. About 150 meters from us, there was small arms fire. When a recon group goes in, there’s always someone left behind to maintain communication and help guide the team back. I found that person. Where is everyone?’ I asked. He had no idea. ‘How’s the fight going?’ — Still didn’t know. I told him, ‘When you find out where a sniper can take position — let me know. I’ll be waiting in the car for your signal.’ I gave him my radio. About 40 minutes later, the guy shows up: ‘I’ve got the info.’ We head out along the edge of the forest. Summer homes to the left. We reach the last little street, the one with the trash bins. Sashka — my student and sports buddy — was with me. He’s not military at all. I gave him a crash course over five days, just the absolute basics. He already had a captured rifle. His task was to stay 15 meters behind me and make sure no one came up on me from behind.

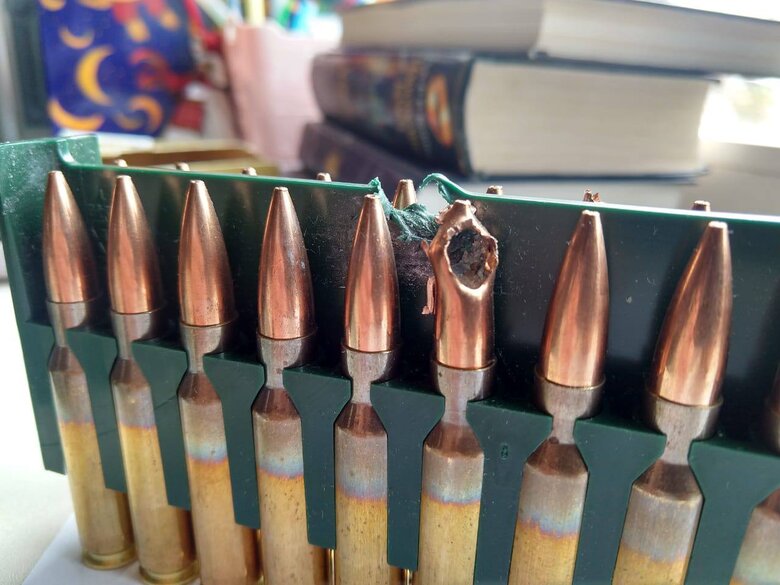

Photo: Andrii shared "finds" like this from Moshchun in his social media posts while trenches were being dug

A soldier from the 72nd recon unit was guiding me. We were about 50 meters from the enemy when suddenly, over the radio, he starts shouting loudly: ‘Guys, where are you? Give me laser marking! Where are you?!’ And that’s when I realized — he had no idea what was going on. I raised my rifle and started scanning in every direction. While I was looking around, I heard a shot from the ruins, maybe 10 meters away. It came from a Russian flanker. In any combat group, someone always watches the flanks — and this one did his job perfectly. He aimed low, not at the chest, but at the pelvis area. Smart move. Just a bit of bad luck for him — and luck for me. The bullet went low and shattered my legs. I dropped. Blacked out. When I came to, one leg was completely numb, the other could still move. I felt around — my left leg was pulverized. I’d been stabbed by fragments of my own bones. I applied a tourniquet. Started calling the guys — nothing. I said, ‘Sania?’ And I hear: ‘I’m here.’ — ‘Where’s here?’ — ‘Behind the dumpsters.’ — ‘Can you see me?’ — ‘No.’ — ‘Then cover the perimeter. I’ll crawl to you.’ And I started crawling. I grabbed onto the dumpsters and pulled myself up. Sania got under me, but he didn’t lift me properly — instead of throwing me over his shoulder like a sheep, which would’ve made it easier for him to carry me, he grabbed me like a backpack. My legs were hanging and flopping around, hitting his knees, slowing him down, and doing me no good either. He carried me for 50–60 meters before collapsing. I told him, ‘I can stay here. If anything happens, I’ll shoot back. You go get the infantry.’ Sania started in with, ‘I’m not leaving you behind…’ I had to yell at him a bit.

Photo: The bullet that entered Andrii’s body first passed through this cartridge

About 15 minutes later, Sania came back with a few soldiers. Two grabbed me under the arms, and a third held me by the pants from behind, lifting my legs. And of course, instead of resting my more seriously injured leg on the one that was more or less intact — and carrying me forward by the pant leg — they had to go the other way. Would’ve hurt a lot less that way. But no! You can’t carry someone feet first, right?" Andrii laughs.

Okay, it was about 70 meters to my car. They got me there and laid me down. Took off my body armor. Sania grabbed my rifle. We’d driven maybe 100 meters when we came across a medevac. I still remember being taken to the first streetlights — and that’s it. I woke up in the intensive care unit a day later. My leg was reconstructed at the central military hospital in Kyiv by Yevhenii Leonidovych Semenets. I stayed in the hospital until May 26. They put a plate in my leg. Since then, I’ve been classified as limited fit for service. Within a month, I got the paperwork done, and my friends arranged for me to go to the Czech Republic for rehabilitation.

- While you were being operated on and recovering, were you still keeping track of what was happening in Moshchun?

- A lot of people I knew were operating around Kyiv during that time, and their updates were flowing straight to me. My phone was constantly plugged into the charger. And if I wasn’t under anesthesia, I was relaying info from one group to another. And it really worked. That’s how it was all through March..

- You said it was your third injury. What about the first two?

- The first time was on April 26, 2019. Near Popasna, there’s a village called Novooleksandrivka. I was setting up a position there. The guys covering me missed an enemy sniper. He fired at me with an SVD. He missed — but the bullet hit my left thigh on a ricochet. I wrapped myself up, reported to the brigade commander, and went to the medics.

There was a military hospital in Hirske. Once, I’d had a piece of glass stuck in my hand, and they took it out there. I really liked how the surgeon worked — that’s who I was heading to. I show up, and the medics say, ‘Don’t get in the way, we’re waiting for a wounded soldier.’ — ‘I am the wounded soldier.’ — ‘Show us.’ — ‘Just get the bullet out quick, and I’ll head back — my guys are waiting. But it wasn’t that simple. I ended up staying at the hospital in Sievierodonetsk for a bit too. That’s where I crossed paths with Hlib Babich — he was in for some heart issues. But I bounced back pretty quickly.

And in 2020, in Avdiivka, across from Hospodarochka, I went out beyond the zero line with a soldier whose call sign was Ptitsa — a completely fearless guy. But no one told us there were tripwires set up. We ran into one of our own. Triggered it. Got blown up.

I’ve always insisted that soldiers should be trained to work with tripwires using training grenades. If someone knows what they look like and how they work, there’s a much better chance they won’t get blown up by one. One time, I traded a box of training grenades for a bottle of cognac. During the ceasefire in 2020, I trained my platoon regularly: trench fighting, tripwires, tripwires again, walking over tripwires. I’m proud that thanks to those skills, almost all of my guys are still alive. Serp and Kot were killed, and in 2023, we lost Niama — a brilliant fighter. But everyone else is still serving with honor.

Until August 2024, I still had hope I’d return to the front. In the meantime, I trained someone who’s now the best sniper in the Armed Forces of Ukraine — highly effective. He’s already a unit commander. I thought I’d be joining his unit, but I was declared unfit for duty... So I turned to developing a rehabilitation program for veterans and wounded soldiers.

I’m one of the first CMAS-certified instructors in Ukraine — that’s the World Confederation of Underwater Activities. I’m a diving instructor, and also a coach in underwater hunting. I’m also a certified trainer in freediving. There’s another discipline — competitive underwater target shooting. Here’s what I came up with. There are so many people out there who need something to do — something meaningful, something that makes them feel needed, something that gives them an outlet. Not long ago, CMAS introduced a new sport: diving for people with disabilities — both sport diving and freediving. That means people with disabilities can compete in official events. We can train them in pools, give them access to a different environment. On land, people with disabilities are heavily affected by gravity. But in water, gravity is zero. During training, they get physical activity, breathing exercises, and the experience of weightlessness. We open a new world for them — one where they feel capable again. We help them learn to manage themselves, to regulate emotions, to do something interesting, and to connect with others over it. I ran my own diving club for 20 years. The greatest achievement of that club, I think, is that it became a real community of friends — not just about diving, but real connection. We organized lake clean-up days and hosted various events and celebrations. I also have a yacht captain’s license. The friend who taught me is now running sailing charters for veterans and people with disabilities. My next goal is to get my captain’s certification confirmed, so I can join these charters as well. So right now, we’re looking for people who are interested. People who want to support the movement. In my dive program, I already have help from a medical center — all we need is people. Veterans and wounded service members. We offer free pool training for them.

Just last week, we talked with Taira — we’ve known each other forever — about what we could pitch to Prince Harry to get underwater target shooting added to the Invictus Games. We could train the athletes for it.

Andrii lives over a thousand kilometers from the sea. But at international competitions, he’s been known for years simply as ‘Always Ten’ — because he always ranks in the top ten worldwide.

- It took me 15 years to get there," Andrii smiles. "I’ve had podium finishes too, but for the past 15 years I’ve consistently stayed in the top ten."

My interviewee switches to English instantly when needed. He speaks Ukrainian too, though he takes more time to find the right words. He spent most of his life speaking Russian. But here’s something I noticed: when talking about combat, he doesn’t use profanity — which is quite rare among soldiers. He only swears when quoting someone, to preserve the original phrasing:

- I believe the fight shouldn’t be for the Ukrainian language itself — although it’s absolutely important — but rather against the use of profanity, which is one of the main weapons of the katsaps," Andrii explains. "If we learn to stop swearing — we’ll win. Profanity is a way to express disrespect, contempt, to humiliate. A person who swears insults not only their listener and everyone around them — but also themselves. At one point, my whole platoon talked me into taking a sniper training course that had just started up. And we really did go through it as a full unit. I’m pretty sure it was the only training session in history where no one used foul language — not even the hardcore swearers, the kind who can barely say one clean word for every eight obscenities. And they stopped. I believe that matters too.

There was another situation back in 2017. I was working very effectively in Svitlodarsk at the time. Opposing us was a group led by someone named Deki — Dejan Beric. I hit them pretty hard. I was working with Ronin — he came from Latvia to fight for us, his father was Ukrainian. Sadly, Ronin was killed in 2018. He had spent many years working in the UK. So on the front line, we tried to speak English with each other. At one point, Pushilin went on TV and said, ‘We’re being attacked by a group of American special forces.

- How are you planning to restore your apartment?

- I haven’t really thought about that yet. See that woman with the flowers? That’s my neighbor from the fifth floor. She lost two grandsons in Building No. 5. And a month and a half ago, her husband passed away… Now that’s real tragedy. I think it’s almost impossible to find anyone in Ukraine who hasn’t been traumatized by this war. But despite everything, we all have to keep working toward our victory. That’s what matters most right now.

P.S. Any help for Andrii would go a long way. His bank card number is: 5363542106188353.

Violetta Kirtoka, Censor.NET