Infantryman Roman Boiko: Gas quickly filled basement area, I felt my eyes, throat, and nose starting to burn. Breathing became difficult.

When Roman Boiko decided to volunteer for the front line, he understood he would need to undergo extensive training to join the unit he had chosen. Reflecting on boot camp — what’s known as "day zero" — the 28-year-old National Guardsman says it was an honor for him to earn the Azov patch.

Roman spent a year and a half fighting in the east. He sustained severe leg injuries but, despite heavy shelling and gas exposure, managed to make it out of enemy-controlled territory.

He is currently undergoing prosthetic treatment in France, so our conversation touched not only on frontline experiences but also on what it takes to ensure the successful rehabilitation of wounded soldiers.

"ZERO DAY IS A TEST MEANT TO SHOW WHETHER YOU CAN HANDLE IT - PHYSICALLY AND MENTALLY"

- Roman, have you been serving with Azov for long?

- Since 2023. That was when our commanders returned from captivity and recruitment into the unit began.

- Weren’t you afraid to join after what happened in Mariupol, at Azovstal? Those men and women proved they would carry out their orders to the very end. We all saw how long they spent in captivity—and how many have yet to return.

- I wasn’t afraid. I trusted this brigade. Even though I didn’t know anyone there at the time, I knew the people joining would be highly motivated because everyone comes in as a volunteer.

- I heard that the selection process is quite serious and you need to be in good physical shape. Did you also have to pass such a selection?

- You may have seen videos showing how Azov fighters undergo their basic combat training and the so-called "Zero Day." "Zero Day" is an exam designed to test whether you can handle it—both physically and mentally. You know it’s coming, you prepare for it, wait for your turn—but it still hits unexpectedly. You don’t know exactly when or how it will happen. At some point, they line you up under the pretense of delivering routine instructions and then suddenly, gunfire breaks out. The rounds are blanks. Everyone is ordered to hit the ground and either crawl or run to their tent to grab their gear. From that moment on, you have to carry your gear with you at all times—crawling, jumping, running, squatting with it, and doing all sorts of physical exercises.

- What happens if you can’t handle the pressure?

- You ring the bell, and that’s it for you. But unlike before, you don’t go home anymore. Now, under martial law, you stay with the brigade regardless—people are needed, so there will be tasks for everyone.

If you don’t ring the bell, you continue the course, which lasts five weeks. You also have to pass a series of exams—covering theory, practical skills, and physical training. If you score enough points, you receive the Azov chevron. It’s an honor to earn it.

If you fall short on points, you still have a chance to receive it later, based on your combat performance.

- When did you receive your chevron?

- After completing the Basic Combat Training Course (BCTC).

- Did you ever feel like giving up at any stage?

- No, never. I came in with a clear goal. I knew I wanted to join this unit, and I understood it would be hard. In moments when you’re completely exhausted, collapsing from fatigue, and the instructors are shouting that you’re weak, it actually gives you a push. You try with everything you’ve got to get up. Maybe that’s how they filter out the weaker ones, but I thought the instructor saw how hard I was trying and pushed me on purpose—to motivate me even more. There were times when my hands were shaking, but I still forced myself to do push-ups.

- Reminded me of the movie "G.I. Jane," with the tagline: "Failure is not an option."

- Haven’t seen it.

- Sounds very similar to what you’ve described. That film also showed intense training, constant challenges and the temptation to quit early.

- The temptation was there. You’re lying face down in the snow because you’re completely exhausted. But at that moment, you remember why you’re doing all this—and you keep going.

- Roman, what did you do before the full-scale invasion?

- I was a manager overseeing several stores in Dnipro. At different times, it was between three and five locations of the same retail chain. We sold Dutch cheeses.

- Why did you decide to volunteer a year after Russia’s invasion, when many were already trying to avoid mobilization?

- I had been donating before that, but I felt ashamed not to be serving physically because I believe a man should defend his country. I wanted to join the guys on the front line. I knew they had no one to replace them, that they were exhausted both mentally and physically, with many wounded and killed. That was when Azov started putting out recruitment ads, videos about the first BCTC.

I was scared. For a while, I hesitated. But then I made the decision, submitted my application, and started preparing.

- Had you done any sports before, or did you have to prepare physically as well?

- I worked until 6 p.m. every day, so I didn’t have much time for sports. But I used to go to the gym after work and did strength training. But for the BCTC, you needed endurance, so that meant CrossFit. I started running actively. That was an issue for me—I could really feel it.

- Did you manage to overcome it?

- To score 100 points on the BCTC physical test, you had to run 3,200 meters in 13 minutes. Before BCTC, I was doing that distance in 17 to 20 minutes. But I passed the test in 14 minutes. I kept running both before and during the course and that’s how I improved my time.

- It really takes strength of character—not only to volunteer for the front but to fight for a place in a specific brigade.

- My only regret is that I joined too late. If I’d known how incredible it would be, I would’ve done it sooner.

- I’ve heard a lot of good things about Azov, but that’s the first time I’ve heard such an assessment.

- It’s all held together by the people who came there to serve. You feel like you’re part of a family and in a family, it just feels good.

The training here is truly intense. There’s no such thing as being written off. If something doesn’t work out, they keep training you. If they see your push-ups are weak, they’ll build your strength. If you shoot poorly or can’t run fast, they’ll work on it with you. The instructors pay close attention. They help you fix mistakes. They yell that "Azov is for the strong," but they don’t humiliate you. And over time, you realize that it’s all meant to make you stronger and braver. They just want us to feel what service really is—that it won’t go the way you want, because you have to follow orders. They prepare you for that, both mentally and physically.

- Did you serve in the infantry?

- Yes. Over time, I became a squad leader, but I started out as a rifleman.

- Did you begin on the front line with assault operations or defense?

- The first mission was just entering the position—we were rotating in to relieve another unit. There were enemy "waves" coming in, but no active assaults at that point.

Still, that first deployment to the position really stuck with me.

- Tell us about it.

- In theory, we knew what we were supposed to bring. We also asked the guys who’d been serving longer. But the amount of food we packed—you should’ve seen it! (laughs - ed.)

When we got to the drop-off point, shelling started. We threw all our stuff down and ran for cover without it, planning to come back for it later.

"The guys joked later that we barged into the trenches way too loudly—everyone else had gone in quietly before us," he laughs, recalling his first deployment.

"We came back to the spot where we’d left our gear about two hours later. By then, it was already dark, and I couldn’t find my own backpack. But I did find another one—with food and water in it, too."

But that wasn’t the end of our little adventure. Since it was our first time, the guide decided to take us along the trench line. And that route was twice as long as the ones we would usually take later. He was just worried about us—since we had no experience, he took us through the trenches so we’d have cover if anything happened. In the end, it took us about an hour and a half to reach the position. There was an enemy drone constantly flying overhead along the trench line, so we had to keep hiding the whole way. By the time we got there, we were soaked and exhausted. We thought: "Is it going to be like this every time? You get to the position, and you’re already done. You just sit down, everything hurts." (he smiles -ed.). And I was freezing, too—my lost backpack had all my warm clothes, and the temperature dropped sharply in the evening…

On the way back, the guys took us through the forest—it took maybe 15 minutes. That experience taught us not to go through the trenches again unless absolutely necessary. It just wears you out.

By the way, this all happened on New Year’s Eve. We were on position the night of December 31st into January 1st. "Quite the night," as they say—we were shelled with everything they had. Back then, we thought the shelling wouldn’t get any worse. But it did. And not just once. You think that it will never happen again, but the war proves that it is not over yet.

- Were you fighting in the Donetsk region at the time?

- No, it was in Luhansk region. The Serebriankyi Forest near Kreminna. After that, we had a short break—some training at the range.

A few weeks later, they gathered us in the morning and said there was an assault underway and a volunteer group was needed. I was one of them.

But another group went in before us. The guys carried out a successful assault, so when we arrived, we moved in to secure the position. That group pulled back because they were exhausted, and we took over the defense.

Since then, it’s mostly been holding defensive positions in different areas.

- Did the enemy try to storm your positions often?

- They did, especially in the swamps. It was very green there—visibility was maybe five meters, and beyond that, just bushes and trees. It was easy to crawl up unnoticed. That’s where they tried to storm us the most.

- Do you believe in luck in war?

- I do. I don’t know how, but it works. When something lands right next to you, you catch yourself thinking: how did it not hit me?

- Were there any moments when you felt truly lucky?

- There was one situation near Kreminna. We were pulling back from our positions in the Serebrianka Forest and heading to the evacuation transport when a mortar shelling started. Everyone scattered and took cover where they could. But one of my brothers-in-arms didn’t make it—he got hit. He was screaming in pain, and the shelling didn’t stop. What do you do? I ran to him.

He’d taken shrapnel to his right arm and leg—major bleeding. I applied tourniquets. Then I started looking around, hoping someone else might be nearby—I couldn’t carry him alone. But no one was there. So I dragged him under a tree and got on the radio to call for help.

That’s what I call luck. The mortars kept falling non-stop, but not a single one hit the tree we were under.

- Did you manage to evacuate him?

- Yes, though not right away. The guys and I managed to carry him to a dugout where there was a medic. The medic packed the wounds and did everything he could to stabilize him. But we ended up spending the night in that dugout—there was a Russian drone hovering overhead. Every time we tried to move out, the shelling would start again.

- Roman, when you ran under fire to help your wounded comrade, did you realize you could be killed?

- I did. According to the rules, you're not supposed to provide aid in that kind of situation, you’re supposed to drag the wounded out first. But the only chance to help him was right there, under fire. I’m just glad we both made it out alive.

"WE WERE THE LAST TO WITHDRAW. THE ONLY POSITION FOR A KILOMETRE AND A HALF. SEMI-ENCIRCLED"

- Which battle was the hardest for you?

- The last one, in Nelipivka, when I was wounded. We held that village for quite a while.

- Was it heavily assaulted?

- At first, the enemy was sending in small groups—three or four soldiers at a time. Apparently, they’d been told that there were no Ukrainian troops in the village, that we were in the neighboring one, because Russians came in really relaxed. Maybe it was for reconnaissance. Though there were also times when they launched real assaults, even coming in with armored vehicles.

We were the last ones to withdraw. The only position for a kilometer and a half. Semi-encircled. But at first, the enemy didn’t know we were still there, so we relayed intel on their equipment and manpower, which we partly saw and partly intercepted over radio. That allowed us to take them out.

One evening, we got an order that a Vampire drone would drop anti-personnel mines, and we were to mine the road. The idea was that the Russians would either spot the mines and stop or drive through and hit them. That night, eight mines were dropped to us.

- Was it difficult to lay mines under those conditions?

- It was asphalt, so it was hard to conceal the mines. But we managed, and they didn’t spot them right away. A few days later, we saw a enemy drone fly over that spot. Then another one showed up—this time dropping munitions—and started detonating the mines.

We were just three meters away behind a wall thinking, "Dear God, let none of those mines land on us."

After we reported what had happened, we got a new order—to mine the road again. This time it was easier, because the road was full of craters. So there were spots where we could place the mines and hide them. We planted them and buried them under soil. And we did such a good job that even our own thermal drone, which flew over the area, couldn’t locate the mines. They even asked us again if we had actually laid them.

The next day, we were assigned another task — to mine a different section of the road, so there would be two lines of mines. But the first time, we laid the mines just three meters from our position, making it hard to detect us — you’d dash out, place the mine, and dart back in. The other section, though, was open terrain with no trees, and it was farther from the bunker.

We hauled in the mines and set them up. Then we were told that, according to intercepted communications, the Russians had seen us laying the mines but failed to track where we went afterward. We were ordered to remain in the bunker. But the next morning, an enemy drone located our position. That’s when a massive bombardment with drone-dropped munitions began.

- Where were you at that moment?

- In the cellar. The room was L-shaped, which made it a good hiding spot — a drone couldn’t fly in directly. The day before, we’d even covered it with a door from above, so from the outside it looked like a collapsed basement.

But they smashed that door and figured out where the entrance was. Then strike drones started trying to breach it. They didn’t manage to fly inside, but they shattered the wall. The enemy then used a regular FPV drone equipped with an instant-action munition. It fell and exploded on impact. We weren’t harmed. Then they started throwing grenades at us. But we were ready for that too. We’d built a small stone wall at the entrance — so the grenade would hit it and explode right there at the doorway. You might get a bit concussed, with gunpowder smoke and dust all over, but the shrapnel won’t get to you.

- How did you get out of there?

- Military luck. It started to rain, the drones stopped flying, and we changed position — moved to a house on the outskirts. We stayed there for three days. Then we were told to prepare to withdraw, as the enemy had stepped up activity.

- How did you get out?

- We pretended to be Russians. After 18 days, all our tape had worn off. Our guys knew our route, knew what we’d be wearing, and the fighters at the nearest position had been warned not to open fire on us. We actually managed to make it even a bit past that position — until an enemy drone spotted us. It dropped a munition. And just as lucky as we’d been for those 18 days, that’s how unlucky we were at that moment. The munition landed right at my feet. Both my legs gave out instantly. I couldn’t feel anything below the knees. Sudden numbness and heavy bleeding. I put a tourniquet on my left leg myself, and my comrade did the right one.

They taught us to place the tourniquet as high as possible on the thigh — right up in the groin — in case you can’t see exactly where you’re wounded, to make sure you don’t bleed out. But I could see where I was hit, so I decided to place it just above the knee. I figured, if something goes wrong, at least maybe I’ll keep the part of the leg above the knee.

- Did the shelling stop?

- No. That’s why my comrade ran for cover. And I was left lying in the open field. I just lay there thinking it was the end. Regretting things I hadn’t said to people. Wishing I’d talked more with my mom before the mission.

Meanwhile, the drone drops kept coming. After the fifth one, I decided to play dead. I positioned myself like I’d gone stiff, lifeless.

- Did they buy it?

- They dropped two more on me. One of them broke two of my fingers. I held it in. After that, I listened - silence.

- But you couldn't walk anymore...

- I felt a rush of adrenaline. Maybe because, at that moment, I realized I was going to live. So I started stripping off my armor, backpack, and tactical vest — and began crawling. I crawled for about 150 meters. Reached my comrade, who was sheltering nearby. But the moment I got into the shelter and he rushed to adjust my tourniquets and see what else he could do for me — the shelling resumed. Then the worst happened — they threw gas into the basement. And we had nothing to protect ourselves with. My gas mask was still in my backpack, back where I was hit. My comrade didn’t have one either. So we made a split-second decision: he would get out, and I would stay. We didn’t have time to think it through. We knew that if the gas was lethal, at least one of us had to try and make it out. I couldn’t crawl out on my own. And he couldn’t drag me out alone either — the entrance had been deliberately barricaded to prevent anything from flying in.

- I’m almost afraid to ask — what happened next?

- The gas filled the basement area very quickly. I felt my eyes, throat, and nose start to burn. Breathing became extremely difficult. Every breath felt like fire inside my chest. It was terrifying. And it lasted for about an hour and a half.

The only good thing — the shelling stopped. Apparently, when my comrade ran out of the basement, the Russians assumed no one else was left alive inside.

- Did your comrade come back?

- When I started to come to my senses after the gas, I began thinking about what to do with my legs. The tourniquets were still on tight. I looked at my watch — it was almost 3 p.m. And I’d been wounded at 9:30. I thought, "This is it. Conversion can’t be done anymore." You’re only supposed to convert within the first two hours. Four at most. So I focused on doing everything I could to keep from bleeding out. One leg was still bleeding. Luckily, I remembered I had another tourniquet in my pants pocket. But I didn’t have the strength to tighten it. A guy I was talking to over the radio helped. I heard the radio come on after the gas cleared my head, and I reached out to a nearby position. I told him I didn’t have the strength, and he said: "You’ve got this. Don’t give up. Rest for five minutes, then do it." When I finally managed to tighten it, he said they’d come for me — but I had to wait. The area was too dangerous, and they didn’t know when they could reach the spot. Everything hurt like hell, but there was no shelling, so I waited. Patiently.

The comrade I had gotten out of Nelipivka with came back, and then the guy I’d been talking to over the radio showed up too. We waited together for evacuation.

The evacuation itself — that’s a whole other story. The distance from the basement to the vehicle was maybe five meters, but while they were carrying me, we came under fire again. Two fragments hit the medic. Thankfully, he survived. And the three of us managed to get out together. Later, I found out that they had cleared a path through a minefield just to get me out. The road had been mined by our side to stop the enemy from advancing. The guy who cleared it was wounded too. So the same vehicle evacuated him along with us.

We actually met properly for the first time later, in the hospital.

- What was your reaction when you came to after the surgery?

- I wasn’t surprised that I’d lost my legs. I was more worried about how my mom would take it. I accepted it calmly. I knew what I was signing up for — and this wasn’t the worst thing that could’ve happened to me.

- Did you find the right words to tell her?

- A girl from the Azov support team helped me. She was the first person I saw after the doctors. When we talked, I told her about my worries, and she offered to call my mom herself. Later, when my mom was by my side, I didn’t let her get sad. She smiled and was just like me — because I hadn’t changed. I joked, I told her how I was doing. It was just normal life, with an injury.

- So you didn’t allow room for depression — not for yourself, not for those around you?

- I didn’t. When friends or fellow soldiers came to visit, you could see it in their eyes — they didn’t know how to act, what to say. But within the first few minutes, I showed them I was still the same person I’d always been (smiles – ed.). And then they didn’t hold back either — they’d joke around, they didn’t feel awkward anymore.

- I listen to you and think about those instructors who were there on "Zero Day." They strengthened not just your body, but your spirit too. Was the rehabilitation difficult?

- I spent about three weeks lying down. I couldn’t sit up — it was too painful. But little by little, I started raising the bed, changing my position. And eventually, I learned how to sit again.

I’m grateful to the doctors and nurses at the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) hospital for how they treated me. They kept checking in, always asking: "Did you sit up today?"

As soon as I could sit properly, the doctor said, "Well, if you’re sitting, it’s time for the wheelchair. Five minutes — then you lie back down."

I ended up riding around for four hours. It was pure joy after lying down for a month. I even went to visit a fellow soldier who was also in the hospital after being wounded — surprised him.

Then came the rehabilitation. I trained every single day, didn’t skip a session. I even came in on December 31 and January 1. The day before, the rehabilitation therapist had joked, "Don’t let me see you here on New Year’s." And at 9 a.m., I walked in like, "Good morning!" Because I knew — my muscles needed to form. It would help me learn to walk later. And it really has helped. Right now I’m undergoing prosthetics treatment in France, and the rehab specialists say I’ve got great stability. I’m already standing on training prosthetics

- Do you also train every day now?

- Yes, for 3-4 hours with breaks.

- How did you learn to swim again? I saw your interview after the injury — you were in the pool.

- I was a good swimmer even before. I loved the water and summer. So the first thing I wanted to do once I recovered was go to a pool. My rehabilitation specialist allowed me to try once my residual limbs had healed. The MIA runs a program called "Unbroken," which includes sports — pools too. So I went.

The first time wasn’t easy. When you’re a strong swimmer, you use your whole body to stay balanced in the water. As soon as I got in, I sank — the body was heavy, and without legs, I couldn’t balance. I started paddling with my arms. That’s how I slowly learned to stay afloat using just my upper body. It took time and effort. But I figured it out. And when I return to Ukraine, I’ll keep training.

- In the interview, you said you wanted to skydive. Have you dropped that idea?

- Not at all. I do understand how hard it will be. I can’t jump solo, and a tandem jump is tricky too: no one knows if the instructor can take an extra 60 kilograms on the harness. And I won’t have legs to absorb the landing. But I still hope I’ll manage to do it one day.

- Do you plan to keep serving with Azov?

- There’s not a lot I can do right now. Sure, I could be clerk, but the problem is I need to keep building muscle and stay on my feet—I can’t sit for long. So I have to find a job that lets me move around and is adapted to my condition. I do have an idea, but I haven’t told anyone about it yet.

- Give us a hint at least.

- I think support teams should include people who have gone through rehabilitation after serious wounds and want to help other fighters. Say someone like me visits a soldier with two high-level amputations: I bring a positive attitude and understand exactly what he’s experiencing. I don’t need to say, "Look at me"—he’ll see for himself that I’m not there to tell him, "Don’t worry, everything will be fine," but simply to talk, ask how he’s doing, find out what he needs. I hope that will motivate people with severe injuries to keep living a full life.

Tetiana Bodnia, Censor.NET

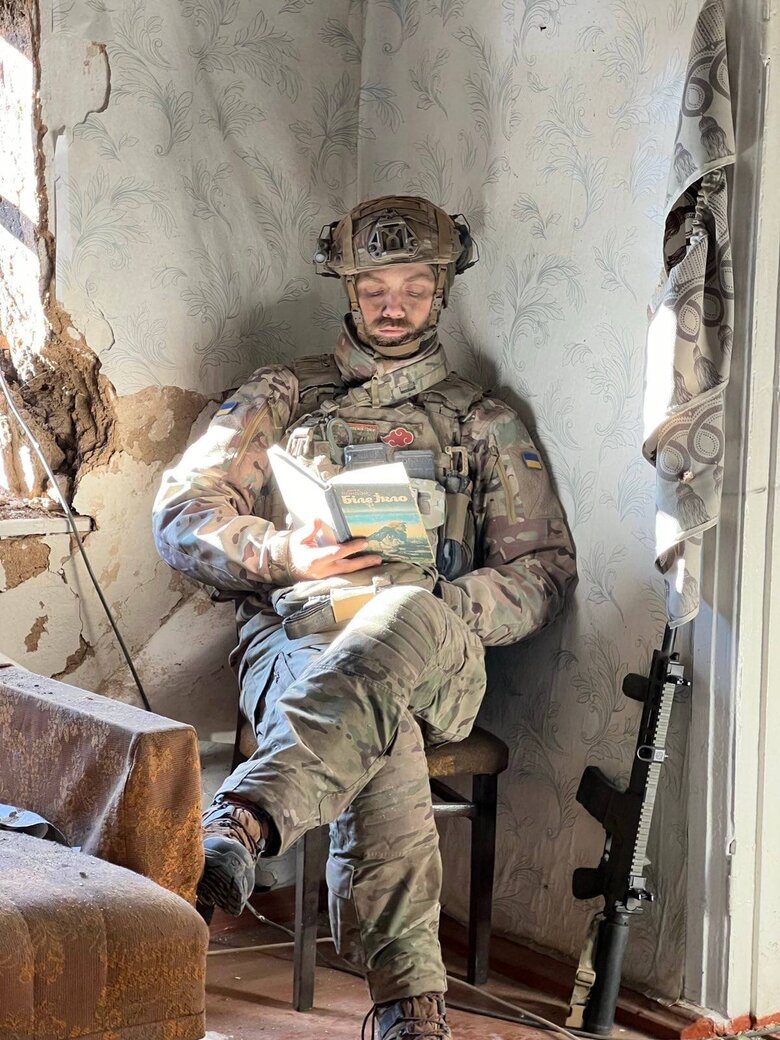

Photo courtesy of Roman Boiko