New prosecutor general, Poroshenko case, and warm bath from "disinterested" People’s Deputies

For more than six months, Ukraine had no Prosecutor General. Andrii Kostin, clearly a protégé of Andrii Yermak, left the post in November 2024 amid a scandal over prosecutors’ pensions and a bogus disability claim. Since then, various rumors about potential candidates circulated, but no Prosecutor General was appointed. And that played right into the hands of the People’s Deputies; without someone in that role, no new charges could be brought against them. Until one particular case made a notice of suspicion a matter of urgency.

So, on June 16, it became known that Ruslan Kravchenko, the 34-year-old head of the State Tax Service, is set to be appointed Prosecutor General.

Ruslan Kravchenko was born in Severodonetsk, Luhansk region. He graduated from Yaroslav Mudryi University.

In 2012, he became an investigator at the Sevastopol Prosecutor’s Office, evacuating case materials from Crimea and serving in Debaltseve. In 2014, he transferred to the Rivne Prosecutor’s Office, then to Lviv’s. By September, he was already working in the Prosecutor General’s Office under Anatolii Matios.

Kravchenko’s first high-profile case involved Russian intelligence officers Oleksandr Aleksandrov and Yevhen Yerofeiev, who were later exchanged for Nadiia Savchenko. Next came the "Tornado" case, targeting military personnel accused of illegal detention or kidnapping, torture, driving someone to suicide, and rape.

After that, Kravchenko became the prosecutor in the state treason case against Viktor Yanukovych. For this case, the Basmanny Court in Moscow even issued a warrant for his arrest in absentia.

In 2019, he became Deputy Military Prosecutor for the entire Central region. In March 2021, he was appointed head of the Bucha District Prosecutor’s Office. It was during this year that he had to investigate Russian war crimes in Bucha, bringing him under the spotlight of Bankova.

In 2023, he was appointed head of the Kyiv Regional State Administration after Oleksii Kuleba was transferred to the President’s Office. Kravchenko was generally considered a competent head of the RSA (Regional State administration - ed.note).

However, just before the New Year 2025, he was transferred to the tax service, where it was clear he felt out of place.

By that time, the Prosecutor General’s seat was already vacant, and Kravchenko was named one of the top candidates.

"He has long dreamed of becoming Prosecutor General. Frankly, I can’t say anything bad about Kravchenko, and he’s probably the best thing to happen to the Prosecutor’s Office in recent years," an interlocutor told Censor.NET.

However, Kravchenko faced a challenge in real life: a competition where he was also considered a frontrunner—until the topic of integrity came up. This was the selection for the head of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU).

One of the first questions posed to Kravchenko during the interview concerned how, with an income of 231,000 hryvnias in 2016, he managed to save 162,000. Kravchenko explained that he saved only 102,000 that year, and the remaining 60,000 had been set aside the previous year but did not exceed the declaration threshold.

The selection commission was also interested in how the frontrunner for the position of NABU director in 2018 received a 42-square-meter service apartment, given that his family already had a place to live. Kravchenko acknowledged owning other property but insisted that he had not broken any laws. Moreover, he pointed out that he had deferred his turn in line for several years, during which 70 other prosecutors, who needed housing more urgently, received apartments.

Sources on Riznytska Street confirm that this was indeed the case—that Kravchenko only applied for the apartment after getting married.

However, during the interview, Kravchenko could not answer who gifted his wife an 89.9-square-meter apartment in central Kyiv in 2014. He explained that they married only in 2019, claimed he never laid claim to that apartment, and said his wife refused to name the donor.

The ambiguity lies in the fact that his wife officially worked as an assistant to People`s Deputy from the "Batkivshchyna" and Party of Regions factions, and her father was accused of having close ties with Mykhailo Papiiev. Kravchenko denied any party affiliation in response and reminded that he was the prosecutor who proved Viktor Yanukovych’s guilt in state treason.

Equally strange was the story that Kravchenko’s father-in-law issued him a power of attorney for a Lexus vehicle valid until 2028, of which the candidate claimed to be completely unaware. When asked how their passport data was obtained, it turned out they had it…

And, as with many other candidates, a familiar "sore spot" for Kravchenko was how he obtained his lawyer’s license and why he did so in Poltava. Kravchenko explained that Kyiv had long waiting lists, so he applied to the Zhytomyr, Kyiv Regional, and Poltava branches as well, ultimately choosing to get his license in the region with the shortest queue.

The commission raised reasonable doubts about how the candidate could have completed 550 hours of practice in just six months, especially since Kravchenko himself said these hours were during weekends and evenings. The only factor that prevented the commission from fully pursuing this issue was that Kravchenko renounced his lawyer’s license and submitted a statement to terminate his legal practice on January 30, 2023.

Foreign members of the commission were more interested in Kravchenko’s connection to former Military Prosecutor Anatolii Matios, particularly whether Matios influenced his obtaining the service apartment. The candidate replied that he reported to other superiors besides Matios, and that his relationship with the former Military Prosecutor was strictly professional—they had not met for several years.

It should be noted, however, that Matios holds Kravchenko in high regard.

But the most remarkable reason Kravchenko lost his chance to lead NABU wasn’t the apartment—his rivals had even worse explanations for their wealth.

It all came down to an email.

Near the end of the 2021 interview, one of the commission members, Dragos Kosa, became curious about the email address Kravchenko provided when obtaining his lawyer’s license: [email protected]. He repeatedly asked Kravchenko who that person was. Kravchenko replied it was a fictional character, derived from the German words for "new person." The commission members pressed several times to confirm whether the candidate truly had no idea who had previously used that name. The issue was that Max Naumann was the founder of the League of National German Jews, a group that advocated for the liquidation of the Jewish ethnicity through assimilation. The commission strongly advised the candidate to use Google and change the email address.

That effectively ended his candidacy for NABU director, although Kravchenko contested the competition results.

And now, the most coveted key for NABU and SAPO will be in his hands—the authority to sign notices of suspicion against People`s Deputies. On June 17, that authority was granted to Kravchenko.

Here’s an important nuance: Ukraine might have continued without a Prosecutor General for another six months—if not for the urgent need to sign a new notice of suspicion against the leader of European Solidarity, Petro Poroshenko.

Since 2019, over a dozen criminal proceedings have been initiated against Poroshenko. All of them have been dragging on sluggishly and none have yet reached a conclusion.

But on February 12, 2025, President Zelenskyy added Poroshenko to the sanctions list. According to media reports, the rationale cited his "involvement" in preparing the so-called "Kharkiv Accords" and his organization, together with Viktor Medvedchuk, in a "coal scheme."

The "Coal Case" was opened during Poroshenko’s own tenure. The issue involved the government purchasing cheap coal from South Africa while actually sourcing it from mines in occupied territories that were legally registered in Kyiv. Essentially, this case was part of the conflict between then-Energy Minister Yurii Prodan from Tymoshenko’s team and Ihor Kononenko’s faction.

The case, whose investigation picked up pace in September 2022, is now ready to be sent to trial. Yet it contains one significant nuance. Most pre-trial actions, including searches, were authorised by the Pecherskyi District Court. In April, the court’s presiding judge, Kozlov, announced that he had no judges left. The Court of Appeal therefore reassigned the case to the Shevchenkivskyi District Court, where, ironically, the first hearing took place on Tuesday.

The situation with the Kharkiv Accords is different. It should be recalled that, at the time of their ratification in the Verkhovna Rada, Poroshenko had already been out of the Cabinet for several months. The direct culprits cannot be punished for the Kharkiv Accords: under the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the 16 January laws, People`s Deputies bear no criminal liability for their votes. Yanukovych, his ministers, and members of his administration likewise remain unpunished.

In a blog post on Censor.NET, Poroshenko’s lawyer Illia Novikov noted that, since January 2025, the case concerning the Kharkiv Agreements has been handled by the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI).

"In March, the media leaked an SBI letter to the Verkhovna Rada secretariat demanding ‘certified copies of the laws of Ukraine.’ That’s how we learned that the SBI is investigating case No. 62023000000000007 on these agreements and that it is being led by Artem Yablonskyi," Novikov noted it.

This is not the case that was reviewed by the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC); that one dates back to 2019. Perhaps, in the future, the cases will be consolidated—but that’s not the point.

For both cases, Poroshenko has yet to receive a formal notice of suspicion. In other words, while there is a basis for sanctions, there is no criminal accusation. It’s a bit odd, wouldn’t you agree? However, according to amendments to the law on lifting parliamentary immunity, the Prosecutor General or Acting Prosecutor General must sign any notice of suspicion against a deputy. So maybe they weren’t looking for a Prosecutor General specifically for this case, as some in Poroshenko’s circle believe?

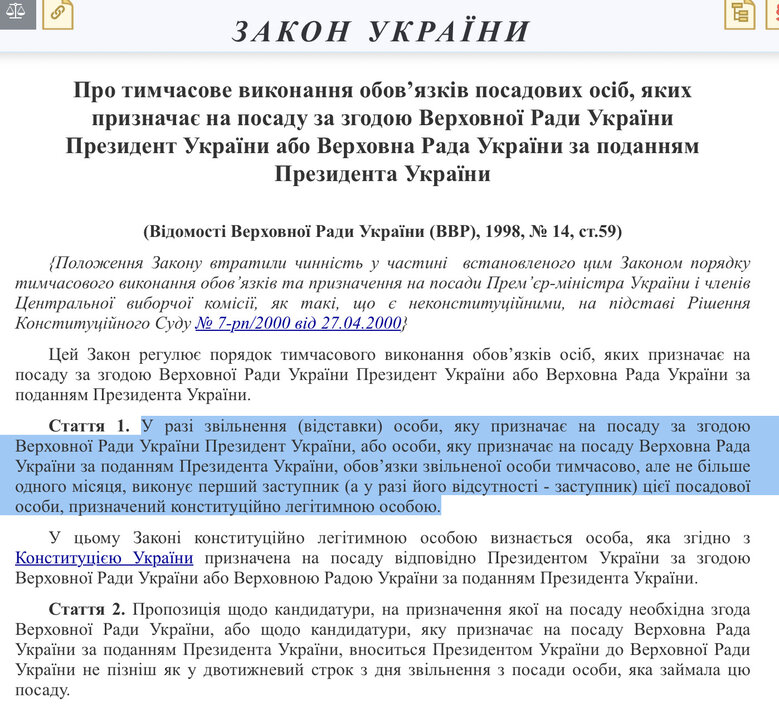

But besides this law, there is also a regulation stating that in the absence of the Prosecutor General due to dismissal (resignation), their duties are performed by the First Deputy (and, if they are absent, by a Deputy) under the terms and procedures established by the Law of Ukraine "On Temporary Performance of Duties of Officials." According to this law, such temporary appointments are granted for only one month, yet Ukraine has been without a Prosecutor General for more than six months.

So, handing over new notices of suspicion became practically impossible.

It’s probably not hard to guess that alongside the issue of appointing a Prosecutor General, the question of delivering a suspicion notice to Poroshenko also surfaced and was often framed as: whoever agrees will get the appointment.

"From what I’ve gathered about Kravchenko, he seems resistant to such pressures. That he’ll stand firm even if the team pushes," said one Servant of the People MP.

On Tuesday, no one directly asked Kravchenko about Poroshenko in the chamber.

Petro Oleksiiovych was not present at the discussion; he stayed in court until almost the vote. We didn’t ask about him personally but focused on broader issues—such as the protection of opposition rights and journalists. Additionally, my colleagues noted that the presentation took place without the president and requested to postpone the matter," explained European Solidarity People`s Deputy Iryna Herashchenko to Censor.NET.

Not only was President Volodymyr Zelenskyy absent from the chamber, but so was the Speaker. The deputies themselves gathered for work only by noon, following a terrifying night in Kyiv.

Before the vote, Kravchenko met with the Servant of the People faction. "Nothing interesting happened there, except, of course, that only 35 deputies showed up," said one majority representative. And although appointing the Prosecutor General is obviously the president’s quota, the involvement of his faction in the process is once again "striking." Though this might be less tragic than reading laws right before voting.

"I have no intention of speaking in abstract slogans. My task as Prosecutor General will be clear and concrete: to keep everyone within the bounds of the law. I see the primary goal of my work in this position as restoring the role of the Prosecutor’s Office as the main coordinator of all law enforcement agencies. During wartime, competition between security forces is unacceptable; we all must work toward a common goal—protecting the state and ensuring justice," Kravchenko stated in his address.

"It is unacceptable for a person to become the target of criminal prosecution merely so that someone can meet a quota, justify holding a post, or flaunt a high-profile case in the media. Rank and status must never be a pretext for show justice, because every such case means broken lives, ruined careers, and shattered dreams. Each formal charge that later ends in an acquittal or in coercing someone into a plea costs years of life, drains state resources, and discredits law-enforcement agencies themselves," the incoming Prosecutor General pledged.

People`s Deputies note that Kravchenko received such a "warm bath" in the chamber that it was almost awkward at times—an impression shared across factions.

"Imagine Kravchenko sitting in the government box while Tyshchenko and Klochko rush over to swap phone numbers with him, and Honcharenko yells from behind: ‘Mr Kravchenko, delete those numbers right away—they’re criminals!’" one deputy recounted.

"I realise every eighth person is walking around under suspicion, but I’ve never seen such fawning. Ruslan’s a good guy, yet this was way too much," admitted his colleague from Servant of the People, suggesting we read the transcript.

Here, for example, is how former OPZZh MP Nimchenko phrased his question: "Mr Ruslan, it is a pleasure to hear a practitioner address the rostrum; it is a pleasure to hear that you have passed through the mill of combat, that you are an ATO veteran. I have one question for you, Mr Candidate. Naturally, our group will support you, and your youth serves as a benchmark for how things should be forming. I want to ask: how do you regard the prosecutors dismissed during Riaboshapka’s tenure—illegally dismissed under the guise of ‘re-certification’? There are about 600 of them."

Or take Taras Batenko from the "Maibach" group (For the Future): "Ruslan Andriiovych, we are impressed by your principled character, which we saw and heard in your address. We know your biography. I consider it a very worthy résumé for a Prosecutor General candidate, someone who has smelled the gunpowder of war. I am referring, in particular, to your tenure as prosecutor in Bucha."

A question from Oleh Ustenko of Servant of the People. "Mr Ruslan, I really do know you from your work, starting with your time as head of the Kyiv Regional Military Administration, then as a prosecutor, and later as head of the State Tax Service. Your performance genuinely deserves the highest marks; that is an objective assessment. We all recognise the tremendous challenges ahead, and we wish you the strength to meet them with honour."

Kravchenko was appointed with the votes of 273 deputies, including 190 from Servant of the People, 17 from Batkivshchyna, 14 from the Opposition Platform — For Life, 18 from Trust, 12 from For the Future, and 12 from Restoration.

ES and Holos did not vote.

Tetiana Nikolaienko, Censor. NET