"My dream is to hit something harder. Tanks, large ammo depot, or rare radar station" – UAV operator Liana Kononchuk ("Dovbush’s Wasps")

In her drive to be as useful and effective as possible, call sign Konon joined the "Dovbush’s Wasps" — the UAV battalion of the 68th Separate Jaeger Brigade named after Oleksa Dovbush.

Liana has been at war since the ATO days. Back in 2019, in an interview with Censor, senior rifleman Plenokosova (now Kononchuk) spoke about her pursuit of versatility:

- "I’m always trying to do something and learn: sniper courses, paramedic training, battlefield first aid… I have a stack of these certificates. Maybe one day they’ll come in handy…"

There was nothing about UAVs in that interview; at the time, no one yet knew about the Great War or the role unmanned aerial vehicles would play in it. Meanwhile, it is precisely in this direction that Liana’s career recently advanced: driven by her desire to be as useful and effective as possible, callsign Konon joined the "Dovbush’s Wasps", the UAV battalion of the 68th Separate Jaeger Brigade named after Oleksa Dovbush.

About the daily life of the "Dovbush’s Wasps" in this war; how UAVs have changed and continue to change the nature of combat; and how the battalion helps new recruits find their rightful place in the unit, all this is covered in this interview.

- Liana, how did you end up with the "Dovbush’s Wasps"?

- Ten of us arrived from our previous unit to the "Wasps" in early November last year as a detached group to gain combat experience. We spent three months with them, and then transferred officially. Five people transferred through the Army+ system, five by formal reports. But this became possible thanks to personal contacts and pressure from the commander of the "Dovbush’s Wasps" battalion.

- Why pressure? Did they not want to let you go?

-They didn’t want to. At that time, the company was expanding into a battalion, and all detached personnel expressed their desire to stay.

- Were you already prepared to perform UAV operator duties, or did you have to learn on the job?

- Before that, I only had training at the Zhytomyr School (190th Training Center). But that was basic training. It’s like learning to drive a car, but then finding yourself in an extreme driving situation and adapting as you go. It’s the same here. We learned the basics there, but I gained practical experience here, in the battalion. Because before that, for six months, we were only at the training grounds and training flights differ a lot from combat flights.

- In what way exactly?

- For example, when I was at the 190th Training Center, we flew using a ground station. But theoretically, we were told that in war, you’ll be flying with a relay station (in most cases, though ground stations are also used in combat). However, in practice, they never showed it (only diagrams), so I had no real idea what it was. At the training grounds, they also talked about relay stations but no one worked with them back then, only with the ground station.

- Explain to the reader what a relay station is.

- It’s a device mounted on a carrier that transmits the signal from the ground station to the drone itself. Our carrier is the Mavic, but relay stations are also installed on other types of drones. Maybe one day we’ll even use them widely on FPV drones…

Here, in the battalion, I learned to fly the Mavic. A couple of times, I went to the training grounds with the guys, and they taught me the basics. Now, in combat, I operate the relay station on the Mavic. Nobody showed me this at the training grounds or the training center.

The second point is the image in the goggles at the training center. Everyone warned us that it would be different in combat. And indeed, it’s very different, because here there’s a constant "curtain," and you have to switch between channels. It’s like playing the piano; you have to get used to doing it quickly.

- Just for readers who might not be familiar with what a UAV unit does, could you explain what the "Dovbush’s Wasps" battalion is responsible for?

- We have several directions. Personally, I can fly FPV drones and operate the Mavic as a relay station. But there are groups that operate Mavics as payload drop operators. Or reconnaissance. For example, I can operate the Mavic relay, but I can’t do reconnaissance or payload drops, which require additional training.

- Reconnaissance drones are the ones conducting surveillance?

- Yes, they can search for enemy targets, adjust artillery fire, or, for example, they locate a target for us, pass it on, and then record the strike on video for confirmation.

- For many readers living away from the frontlines, drones are enemy UAVs launched from Russian and occupied territories, flying to bomb Ukrainian cities. Could you explain what drones do in your battalion?

- Usually, people think a Shahed is a drone, and an FPV drone is a drone, and Mavics, too. In reality, it’s a very broad term because we’re talking about an entire ecosystem. Our unit’s task is to operate along the close front line, currently, the approaches to Pokrovsk. When enemy sabotage and reconnaissance groups (SRGs) try to break through or conduct assault operations there, we strike them. If there are a couple of quiet hours in that sector, we go on free hunting missions and target logistics routes used to deliver personnel or ammunition. These are 10–20+ km, short-range flights. The main goal is to ensure the infantry’s survival.

- Tell us about a typical day on the job for Liana Kononchuk, a UAV operator.

- Our work is very well-organized. What I liked compared to my previous unit is that pilots who go on missions have time in their free hours both to rest and to train at the training grounds.

Because every mission is a cycle that wears you out. And to do your job properly, you need to rest.

We gather on the day of the mission. We coordinate with the workshop on when the drones will be ready. We order supplies for the combat engineers and the workshop. The driver gathers the team, and we collect the equipment. The most stressful part of the cycle is getting there and back, it’s a lottery.

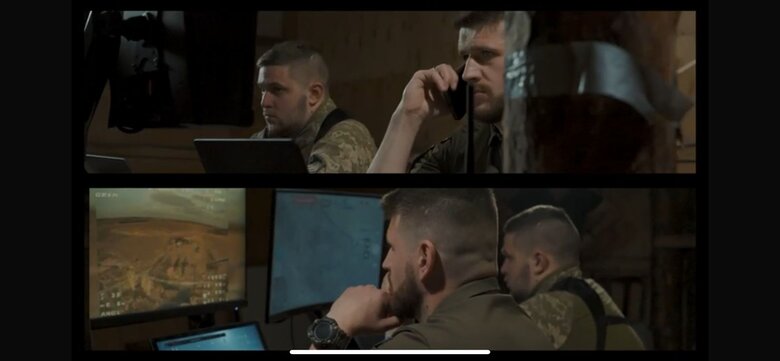

A team of fighters on a mission

Sometimes, 3–4 crews go out and everything goes smoothly. Sometimes, just one goes out, and an enemy FPV drone is hunting them. That happens.

We arrive at the position, check the equipment, and rig the drones. For example, if there’s a lull at night before starting operations, you can catch some sleep or do free flights searching for UAZ vans. During the shift, we work on targets assigned by the duty officers. If the operations officer reports targets, we fly out. If there are no urgent targets, we go hunting freely.

After finishing the shift, we close it out. We prepare positions for the incoming team. Then comes the extreme ride back, followed by rest: collecting water (since it’s rationed by the hour here and not available every day), doing laundry. We go to the training grounds to test new drones and conduct reconnaissance flights. When new recruits arrive, we take them under our wing and teach them to fly. Sometimes a person has transferred or just arrived and has no practice yet. We train them.

- Compared to the newcomers, you’re already a flight veteran.

- I don’t think so, not at all. Most of the time, I end up doing mostly organizational work. Because, even during training, they told us: "Flying is only 10% of the whole process." For everything to work smoothly, a lot of different things need to be done. I can’t yet check off hitting any impressive targets. There are people who have been flying much longer and fly better than me. So I can’t say I’m a top specialist.

- Describe your actions during flights. What do you hold in your hands, what do you watch, and whom do you rely on?

- I’m either an FPV pilot or a Mavic pilot. So, there are two types of actions. Let’s imagine I’m the Mavic pilot and we’ve been given a target. We look at the map to locate the target, figure out roughly where to position the relay station so the FPV pilot has a good signal and video feed, and decide at what altitude to raise the Mavic. We plan the route for it to get there and how best to approach the target.

Next, if I’m operating the Mavic, I escort the FPV drone so its pilot can successfully approach the target. The drone is rigged (we have a dedicated person in the battalion who does that), and then we carry it to the takeoff point. The FPV pilot takes off, then I take off. We fly, escorting the drone. If the pilot struggles to see something clearly, gets disoriented, or has a poor video feed, we can guide them on where to go. When they hit the target, we land the Mavic and put its battery on charge.

If I’m the FPV pilot, I have the controller and goggles. I can also get disoriented or experience poor video quality. Someone can guide me. We select a drone with the appropriate munitions and locate the target. The goal is to fly without draining the battery. If the target is far, you have to stretch the battery charge. (This gets harder in bad weather conditions, when the wind blows against you.) It’s not like you have full charge and rush at full speed. You need to manage the battery to reach the destination. Once the target is found, you strike.

The FPV drone is one-way only, because for us it’s a kamikaze. The Mavic is more complicated. Since I trained and flew FPV from the very beginning, it’s more familiar to me and I like it better. I fly, strike (or sometimes miss, that happens, because not every sortie can be successful due to various circumstances) and that’s it. My job is done. The Mavic flies fine during the day, but at night it’s constantly drifting. Taking off and landing is the biggest challenge.

- Have you had to fly fiber-optic drones?

- I haven’t flown on fiber myself, but I’ve worked in a team that uses it. I know how to rig it, yet I haven’t piloted that setup; there are specialists who handle it better than I do. My turn just hasn’t come yet.

- For the readers, can you explain why everyone is talking about fiber‑optic links now, and how they have changed the war?

- Personally, I wouldn’t pin too much hope on fiber‑optic technology, at least not at its current stage of development.

- Really? Why?

- Because it still needs work. The first versions we received caused plenty of headaches. There’s a fibre wound on a reel, and depending on the manufacturer, the way you use it changes. Sometimes you have to fly higher, sometimes lower, faster or slower, just to make sure the fibre reaches the target. You also have to fly carefully so the fibre doesn’t kink, and someone on the ground can simply damage it on the way.

Right now, the problem is that the Russians have pulled their heavy equipment back from the forward line. Sure, a fibre‑optic drone can hit infantry, but in my view, it’s too expensive and not yet widespread enough. If we could use it against armour or ammo dumps, that would be great, but our spools aren’t fifty kilometres long.

What’s good about it? Unlike regular FPV drones, we get a clear picture and no "curtain" like with analogue links. But in strong winds, the fibre won’t make the trip: it unwinds quickly, the battery drains, and the FPV won’t reach its target. The upside is that the fibre link can’t be intercepted by spectrum analysers the way analogue can. They can’t see our feed, and they can’t jam it because the signal travels through the fibre itself.

Another issue is the strong winds in the Pokrovsk direction right now, which make fibre operations harder, but still doable. I think the system will keep improving and get much better.

(UPD. While this piece was being prepared for publication, Liana had a chance to fly with a fiber‑optic tether. Her updated impressions: "My overall views remain unchanged. There was no wind this time, so we managed to reach the target. But some things are beyond the pilot’s control: the fiber can snag on a branch or someone might step on it. These three sorties were successful in that they happened, yet unsuccessful because the target wasn’t hit. The next day, a strong wind came up, the fiber couldn’t fly, and that’s one reason fiber‑optic isn’t a panacea. Bottom line: the tether works, it flies, and it can’t be jammed — but spool length is a limitation; you also need a specific target to hit right away. There must be a continuous video feed so the Mavic operator can coordinate…")

- You’ve used the slang term "getting a curtain" a few times. What does it mean?

- When you’re flying on a single channel somewhere at the training grounds, your video feed is clear. If it starts to degrade there, it usually means you’ve gone beyond the radio horizon or the antenna isn’t pointed correctly. But here, "curtain" is this annoying interference the pilot gets during flights when enemy electronic warfare (EW) is active. They jam the channels, that’s how it used to be. We got by by hopping frequencies… Now the enemy has intensified these effects, jamming entire frequency bands. So our mechanics have to get creative to find solutions that allow us to fly and strike. When our video feed is good but then suddenly disrupted in a specific way, you immediately recognize it as a "curtain." You switch to another channel, and it improves. But when you lose the video completely, even if you still have control, you see nothing. And without visual confirmation, you can’t hit the target.

- You currently need people because the "Dovbush’s Wasps" are expanding as brigades transform into corps. Is it true that people can join in various personnel roles, including support positions, and then gradually, after training and gaining confidence, move into specialized UAV-related specialties?

- Yes. Even if someone just signed a contract or was mobilized, they first go through Basic Combined Arms Training (BCAT). Then, if training groups are formed (since different training centers have their own schedules), the person can proceed directly to specialized training. If a person has completed BCAT but no specialized training groups are currently formed, they can either join us immediately or wait for their specialized training. While waiting, they can come with us to the training grounds and practice. For FPV operators, there are training programs on PC. Liftoff is the most popular, it’s a simulator game. You need a controller, and you can train. The basics, theory, there’s tons of that online. If you want to learn more, you can visit combat engineers, mechanics, and specialists to reinforce theory with practice, try assembling a drone, soldering, and see how munitions are made. It’s for those who are interested.

- So you can start working in the battalion’s support units. Later, if you want, you can transfer to specialized UAV-related units, of course, after completing the necessary training.

- You have to keep learning all the time. A person can study on their own, that’s one thing for today. Tomorrow, something new appears, and you have to adapt.

At first, a person will train. They might deploy with the unit and feel all the adrenaline and action. We can add a newbie, a trainee, to an existing crew so they can watch how the process goes. The main crew has assigned duties, while the trainee observes and figures out what suits them best in practice — what they want to do. Maybe be the equipment handler, then they need to work with combat engineers to learn the basics. Or maybe they feel flying is their thing. In that case, constant practice is necessary.

A person can also join the workshop. You need to have a drive for innovation here. You constantly have to browse both our and b**tard websites and channels, look for solutions, solder, invent, and experiment.

- On the recruitment site, there are three key specialties: UAV operator, tablet operator (or navigator), and technician. You’ve already explained the UAV operator and the technician roles. What do tablet operators do?

- They are people who must have good spatial awareness and be able to guide the pilot accurately to the target. There are specific requirements for this specialty. For example, if a person has geographical dyslexia, this job isn’t for them.

It’s important to add that the battalion doesn’t just have FPV drones and Mavics. There are also heavy bombers, all kinds of "Nemesis" and "Vampires." I just don’t have any involvement with them.

- What human traits and talents make it easier for a UAV operator to adapt? I'm going to go with stereotypes. Is it true that the ideal recruit is a young guy or girl with experience and love of computers and a good vestibular system?

- Both yes and no. For example, when I first put on the goggles myself, my instructor asked if I’d ever had concussions. I said yes. He replied that he didn’t envy me. Then I put on the goggles, and from takeoff to landing, I felt nauseous and like vomiting. My blood pressure rose and I panicked a bit. He told me to tough it out. And that’s what happened, I got through the first flight, and then it was fine. That happens. But some people don’t have any of that. Generally, if someone wants to transfer from infantry and has had concussions or tremor-related injuries, it might be harder. Though there are exceptions. There was a girl training with me who had a congenital tremor, and she flew amazingly!

So it’s different for everyone. Some pilots are former gamers and they do great! I have comrades who transferred with me, they’re musicians. Some do better, some worse.

- And what does music have to do with it?

- Fine motor skills. I just thought maybe people who do embroidery or knitting should try flying. It could turn out really great…

- You’re the only woman in the battalion? What’s the attitude toward women like?

- No, there’s one more. She was in the unit before me. The attitude? Towards the two of us, it’s normal. If someone else joins, I don’t know. When I came, there was only one woman here and she wasn’t really allowed on combat missions. But now she’s a combat medic, trained up, so it’s all fine. At first, I noticed my guys were going on combat missions, but I wasn’t being taken. I waited a bit, then said, "Why did I come here?" Once they saw I’m a normal person and that my gender doesn’t affect the work, everything settled. If I had panicked, thrown a fit, said I wouldn’t do something, then, I think, I wouldn’t have gone anywhere.

It really depends on the people. Stereotypes seem to be everywhere. Nobody in the battalion told me, "You’re a girl, woman, sit down..." I just had to go out on missions once or twice so they’d see I’m reliable. But, say, if a girl came in and said, "I have a manicure, and I can’t go six days without a shower," or other excuses, then I suspect she’d be rejected.

- Would you recommend that girls who want to join the Armed Forces and go to the front line, but have doubts about their own effectiveness, try to join the "Dovbush’s Wasps"?

- It’s worth a try. You just need to understand all the challenges that await.

- Like what?

- Let’s go through some stereotypes. First, people say, men and women, their health is poor. What can I say to that? I’ve had terrible health since birth. I was supposed to be a childhood invalid. Over my 10 years of service, I’ve accumulated so many ailments that doctors ask how I’m still alive. I can’t run, I don’t know how to swim. But I go to the gym and lift weights. I love it, I do it for myself. I also take pills with me on shifts and that’s how I work.

Second is hygiene. Here where we live, water is supposed to come every two days. But sometimes it doesn’t come for a week. You can try to find a place to wash, but you have to be ready to go without water for some time.

Third, you have to get used to constant hits. Also, the lights are always on at our position because we have to be ready at all times. So you can only sleep with constant light and banging noises. If you don’t get enough sleep in this environment, it will affect your work.

I should also mention the workload. Of course, it’s not like infantry, you don’t have to carry heavy loads all the time. But on position, quick unloading is needed—ammo, drones. And if not every day, then sometimes you’ll have to haul stuff.

- You mentioned some limiting factors. But the main question for motivated people is: how needed do you feel? Does your battalion have a sense that you’re doing something big and important?

- Yes. I constantly watch the Deep State map to see who’s advancing where. I roughly know which brigades and groups are there. When I arrived on this front in November, many predicted that Pokrovsk would fall by winter. Now it’s July 2025 and what do we have? The flanks are slowly collapsing, but our section holds. Isn't this an indicator?

- That’s a clear indicator. Not to mention that the role of drones in this war keeps growing every month.

- Exactly. Of course, our mission here is the frontline. So if someone dreams of flying deep behind enemy lines, sinking Russian ships with sea drones, or flying off to blow up the Kremlin, this isn’t the place for you yet. Our main task is to protect the infantry. And if we know b**tards are approaching the tree line where our infantry is positioned, we have to eliminate them.

- Within your operator service in the "Dovbush’s Wasps," do you have a personal, exclusive dream?

- I want to have some really cool targets credited to me. Those are check marks like you get for downed aircraft. What kind of targets? Tanks, a big ammo depot, some rare radar station. There’s a growing focus on shooting down Shaheds now, and that’s interesting too.

When I arrived, enemy armour was no longer roaming around freely. So if one of their tanks rolls in once in a while, everyone hunts it down to see who gets first crack. My own hits so far have been antennas, vehicles, some b**tards, their foxholes. I haven’t had any spectacular hits yet. I want to hit something harder. That’s one of my dreams!

Yevhen Kuzmenko, Censor.NET

Photos, video: archive of Liana Kononchuk