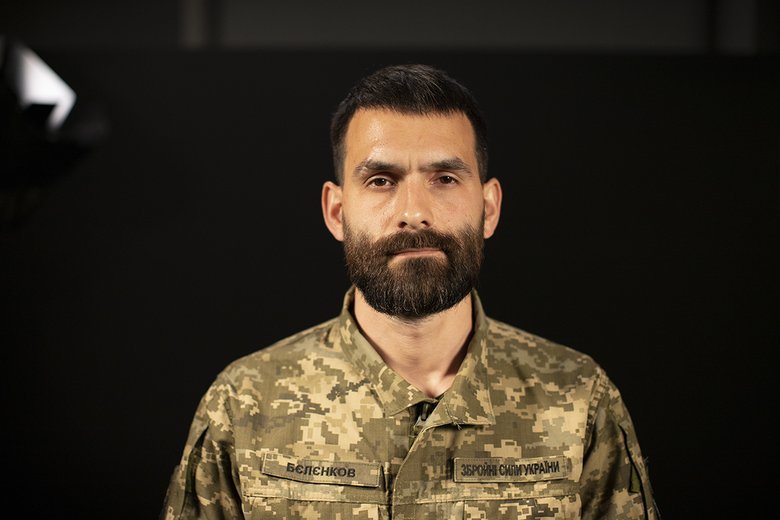

Chief of Staff of 412th Nemesis Regiment Artem Bielienkov: In UAV deployment, Ukraine has realized roughly 25% of its potential. There’s room for improvement

Drone Industry

The interview with the unit’s chief of staff, Artem Bielienkov, was recorded to the droning of "Shaheds" that Russia once again launched at peaceful Ukrainian cities.

Bielienkov came to the military from business. He ran a company that promoted technological solutions for agriculture. Like for millions of other Ukrainians, February 2022 was a turning point. Artem realized his experience could be useful at the front. Still, it took time to get back to the advanced tech he was used to.

He started as an infantryman, was wounded, then joined the Commander-in-Chief’s office, where he was in charge of digitization. Next came reconnaissance with the "Lazar Group," and then Nemesis

As part of the Drone Industry project, Censor.NET spoke with Artem Bielienkov about the culture the regiment lives by, where and how it recruits, and the objectives it pursues. We also discussed UAVs, how essential they are in the Russia–Ukraine war, how hard they are to learn to operate, and whether drones can replace a soldier on the battlefield. The conversation also touched on our international partners, who have finally engaged in these processes but still do not fully grasp what lies ahead.

Warning: this text contains profanity.

– Before the full-scale invasion, you were in business, promoting innovative projects, including in agriculture. How did you end up in the military, and why choose this specific field—unmanned systems?

– Unmanned systems were not my first stage in the Defense Forces. When the enemy stood near Kyiv in 2022, I spent a month and a half in a separate National Police platoon. At that moment, it was the only place I could go, knowing what I was doing and whom I was joining.

After that, I made a fully conscious choice—to join into the 47th Separate Mechanized Brigade. I liked the ideas behind how that brigade was being formed.

UAVs came later. First, I was in the infantry, a machine-gun platoon commander, and I took my lumps. Like everyone who went through the infantry, I was wounded.

I then became a mechanized company commander and later chief of staff of a mechanized battalion. After that, I served in the Commander-in-Chief’s office, responsible for automating situational awareness. These are digital products like Vezha, DELTA, and others: reconnaissance, information enrichment, data acquisition.

I also served six months as chief of intelligence under Pavlo Oleksandrovych "Lazar" in the Lazar Group.

Only after all that did I join the unit where I serve now. First as a battalion chief of intelligence, then battalion chief of staff, and later regiment chief of staff.

So I wouldn’t say I chose the UAV track when I joined the military. I had expertise in drones and used it first in the infantry and then in the Commander-in-Chief’s office. During the counteroffensive, when we were rolling out Vezha in the south (Vezha is a Ukrainian battlefield video-analytics platform integrated into the DELTA combat system that provides real-time drone feeds, improving coordination between UAV crews, artillery, and command posts - ed.), all the coordination naturally ran through UAVs.

In Lasar’s Group, I saw a compelling opportunity to apply my knowledge and experience. From there, moving to Nemesis was logical. I already understood how such an organism operates. I was keen to keep developing professionally in this field, having the relevant army experience.

– Tell us more about the Nemesis regiment. Beyond efficiently destroying the occupier, what does it do, what values does it uphold, what guides its work, how does it motivate its troops and recruit new people?

– When I first joined the unit, there were only a few of us, just a couple of dozen people. Valerii Zaluzhnyi was still Commander-in-Chief then. He was the one who formally established the unit. There was support, several orders under which we transferred around a hundred people to us from other military units. But Nemesis grew out of a small core.

I saw plenty of military units while working in the Commander-in-Chief’s office. Our battalion stood out by having a lot of strong managers "per square meter." It was a cohort of civilians with state-minded and entrepreneurial experience and most already had military experience as well.

When we were forming the battalion, we were already thinking about scaling. It was clear we would become something bigger. The idea behind that growth hasn’t changed. Beyond killing Russians, defending our sovereignty, our territory and our homes, we aimed and still aim to build a unit with processes so well-tuned it can keep operating without us and remain a powerful formation within the Armed Forces, with its own legacy. We are building a systems-driven organization, and that shapes everything we do.

That’s far more labor-intensive than building a unit focused solely on killing Russians. You have to develop, sustain, and balance a lot of functions at once. So this is a unit about system discipline.

We take a genuinely systematic approach to our development, to process organization, even to growth itself. That’s probably the key feature that sets us apart from other players: deliberate system thinking. We also plan the development of our combat capabilities in advance. Not ad hoc, but methodically, step by step.

As for the motivation of the personnel. A unit is a mix of different cultures. State-minded, entrepreneurial, and, ultimately, military culture. They coexist productively here. We also keep the system balanced by assigning people to the right roles, for example, into management, where they have the relevant experience.

The army has principles of command. We follow them. But at the same time, we build in additional creative foundations—team motivation, team growth, and so on.

For most of the team, speaking about the management tier, the motivation is constant growth, new knowledge and experience, new challenges and successful results. For the personnel who directly execute combat tasks or support them, the main motivation is, first and foremost, the results we deliver, plus the infrastructure we build around them to support the team and the human-centered approach.

– What qualities, knowledge, and skills should a person have to serve in the Unmanned Systems Forces (USF)? How much does prior civilian experience help in service?

– I can’t speak for all USF units, each has its own selection approach and nuances. But for us, the key is that a person understands why they’re coming here.

Frankly, in 2025, we don’t have the luxury of being choosy. Back in 2022, I could filter my company three times over, weed people out and find replacements for those who didn’t fit. Now our room to do that is limited.

At the same time, Nemesis has been number one for direct recruiting into a military unit across the Armed Forces of Ukraine for quite a while. We’re a unit that grows organically because our recruiting process is well-built. We built it from scratch on honest dialogue with recruits and a lot of people do come to us.

What kind of people are we looking for? They need to be healthy, ready for changes in their lives, and aware they’ll have to learn intensively and work just as intensively. Those are the basic requirements. I don’t care what motivates them to join us. What matters is that they understand why they’re coming to our unit, what this unit is, and that they’re ready to learn and work their asses off.

– Do many people in the 18–24 age bracket come to you?

– This category has only just opened for us, so for now we’re talking about dozens of people we’re processing while tuning the mechanism to do it faster. It isn’t a flood yet, not because the demand isn’t there, but because we’re feeling out how to organize it properly.

We’re, as a reminder, a systems-driven organization. So we need to understand that we have a funnel that works efficiently—the costs of that funnel, and where bottlenecks arise: interviews, clearances, medicals, psychologists, paperwork, TCRs, and so on. It’s not exactly a challenge for us, but a problem set to solve.

It’s also a young audience. You need a communication logic tailored to them. A typical 18-year-old will see a message I find cool as a grandpa joke. For him you have to use modern tools—TikToks and similar formats. So you need to stay flexible in communications.

– Have there been cases where someone applied to you but ended up, say, in the infantry?

– The infantry is honorable work, go and do the job.

If a person moves quickly and follows the instructions, no one can reassign them, we have direct mobilization into our military unit. The TCR is merely a service point for the Military Medical Commission (MMC). You pass the commission and you come to us. We process the paperwork directly into our unit; we don’t need anyone else involved.

What’s more, we have a unique advantage, our own Basic Combined Arms Training (BCAT). We run it with our own resources. It’s faster and has UAV technologies baked in. It’s an experimental program with a shorter duration. As a result, everything moves faster, in our culture, tailored to our way of doing things. People are already integrated into what we do and understand whom they’ll work with and how. It’s harder with those trained by other centers.

In addition, we plan mobilization measures so that incoming groups immediately slot into the next BCAT cohort. We don’t keep people idling on our infrastructure. They arrive, we train them, and we plug them into combat work. It’s a maximally fast and efficient process.

– How hard is it for someone who’s never worked with UAVs to learn them? And does the so-called "menagerie of drones" get in the way?

– If a person is young, it’s not hard at all. If they’re older, it depends because the older you are, the harder it is to learn something new. Prior experience, reaction speed, and how your brain processes information all matter, because you have to grasp things quickly.

As for the "menagerie," it’s tough, but we’re dealing with it. We grew out of a single strike platform, so we had one well-oiled setup. Now we’re rolling out FPV at scale, fielding interceptors, we lead on intercepting enemy strike UAVs and we’re developing mid-strike class systems.

Read more: How can Ukraine tame "menagerie of drones" and should it be done?

The only real "menagerie" we have is in aerial reconnaissance. That’s how it evolved historically. We either used state funds with a spending deadline to buy what could realistically be delivered within that time frame, or received specific systems as part of international aid. Now we’re trying to structure it and bring more order to the process.

With our other systems, things are more or less worked out—we have a clear SOP in place.

– UAVs have been used since the outset of the Russia–Ukraine war in 2014. At the origins were DEVIRO with the now-legendary Leleka, Ukrspecsystems, Skyeton, and Athlon Avia. But drones only became a true "weapon of victory" in 2022. Today, we have 500+ active manufacturers, over 1,000 drone models, and a dedicated branch within the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Beyond the expanded scale of combat operations, what has changed, greater technology accessibility, an influx of people with fresh ideas and a futuristic vision, rotations in senior command?

– I’d been working with military-grade drones even before joining the army. I ran several companies, one of which, SmartFarming, focused on agricultural innovation. We launched SmartDrones, a project dedicated to UAVs in agriculture. We sold drones and provided UAV-based services, purchasing the aircraft from military drone manufacturers. For example, we collaborated with Ukrspecsystems and also worked with the "Skif" models. Overall, I’d been in contact with these guys since as early as 2016.

That was when active hostilities tapered off and so did volunteering. Manufacturers started looking for themselves in the civilian market to make money. Most moved into agriculture. I was a kind of magnet in the ag sector, pulling in the innovators, so I gathered everyone and organized expos.

For two years in a row at the Kyiv International Economic Forum, we hosted the largest drone exhibition, PD systems, Lelekas, Skifs, and foam-body drones from local makers. I promoted it, at least I tried and brought it into agriculture.

In the end, I walked away from that track. Drones were expensive and service support was lacking. I switched to Chinese platforms, they met the needs at the time.

So the first part of the answer is this, back then very few companies were true large-scale manufacturers. Only a handful had funding for deep R&D to produce effective, high-quality systems. There was no demand because there were no active combat operations and therefore no military customer. For the army to codify anything in peacetime and the ATO period was quasi-peacetime, you had to go through hell. Also, few people inside the armed forces were involved with technology, so there was no money for it.

When I took command of a machine-gun platoon, we were in combat within a month. At that time, I had six different drones, Autel, Mavic, for example. I bought them with my own money and with help from friends. Those drones that we procured for ourselves helped us survive.

I’d launch a drone, see the picture around my military outpost (strongpoint -ed.), understand where things might be, and plan my defensive layout.

Later, when I was at company level, we had 25 different drones. We had two Punisher crews, and there were guys already building FPVs in the autumn of 2022.

Naturally, all these new people started generating a ton of ideas. But there was extreme need, we didn’t have means to bring fire on the Russians. They had more artillery, vehicles, firepower, and ammunition. We needed alternative systems for both reconnaissance and strike.

In other words, people who generated ideas and had some money and capabilities converged in one place. That’s how interaction with the drone sector started, driven by acute necessity. There was no state money for drones then. Nor did the military have an understanding of how to implement it. So the answer is: a concentration of people plus urgent need. People understood we’d only survive if we had this capability, and they set it in motion.

After that, for the industry to mature to where it is today, obviously state-level decisions were required, at the level of the president, the Cabinet with the relevant minister, the General Staff, the Commander-in-Chief, and so on.

To scale production, drone makers needed money. Primarily state contracts. They also needed simplified codification and formal acceptance into service. Of course, partners helped too. They finally understood that drones were worth investing in.

Today it’s a mix. But the beginning was laid by people driven by a hunger for weapons and the fight to survive.

– So the initiative came from the bottom up?

– Definitely and fundamentally, from the bottom up. In spite of the system, not because of it.

– Frankly, the army is first and foremost bureaucracy — a very cumbersome machine that not only dislikes but sometimes resists change. Unmanned systems, meanwhile, evolve extremely quickly. Have you been able to find a balance between innovation and that bureaucratic resistance?

– At the unit level, yes.

Thanks to the size and quality of our team, we can both play by bureaucratic rules, optimizing processes when needed and at the same time push R&D, implement things quickly, and come up with creative ideas on how to do it properly and legally.

At the level of the Armed Forces overall, I believe we’re still far from being truly effective. In terms of UAV employment, we’ve realized maybe 25–30% of our potential at best. Our actual potential is much higher.

We still don’t have a proper combat order structure, or synchronization between units and assets. Training in this area is a complete mess. Most of it happens on individual units’ own resources, through their instructors or volunteer groups. Sure, there are training centers that have grasped some aspects, but overall it’s still not very effective.

At the same time, that’s not a complaint about our army, though. Our army is extremely flexible compared to our partners. I talk to them almost daily now, and I honestly can’t imagine how they’d implement all these changes in their own structures.

In my view, to launch innovative, cutting-edge projects across the army on a large and systematic scale, you first need proper planning. Unfortunately, the army always focuses on solving today’s problem, creating new ones for tomorrow.

There should be a sort of project office in the General Staff, reporting directly to the Commander-in-Chief or the minister. That office would outline a plan for scaling innovation: simply put, "we’re doing this, this, and this but we need to simplify 33 pieces of paperwork." Fine, then issue an order to simplify those 33 papers to launch the initiative as fast as possible. Fine-tune the administration afterward.

In practice, though, once you launch an innovation, the very next day you get 33 reports, 22 briefings, and about 40 working groups and meetings. And it all drowns in bureaucracy.

The first case where I saw something effective above the unit level was the 3rd Army Corps. At the corps level, they structured an innovation component and the rollout of advanced technologies. But a systemic organization at higher levels, capable of managing implementation and innovation launches—I haven’t seen that yet, unfortunately.

Still, compared to where we were in 2022, the breakthrough is incredible. It’s the reform of all reforms.

– Former Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, recently said that the war has reached a positional deadlock, in part because of UAVs, and that countermeasures against drones are needed. Do you agree with him? Does this mean drones have reached the limit of their usefulness?

– The war has been in a stalemate since the end of 2022, after the completion of the Kharkiv and Kherson operations (the Kharkiv operation lasted in two stages from 6 to 12 September and from 12 September to 2 October 2022, the Kherson counter-offensive: 2 August - 11 November 2022 - ed.) Drones allowed us to sustain this positional warfare. Now, with the enemy integrating its own unmanned component, it’s trying to break out of that stalemate. That’s why we have to become more effective.

First of all, it’s about scaling technology. We generate ten times more ideas and startups and launch them faster but when it comes to scaling, we lose like a schoolboy playing poker against professionals.

They don't have a "menagerie" of projects, but they do focus on a few, scaling them up to the point of changing organizational structures, training programs, recruitment, and more.

– How important are technologies for the military? It’s clear that wars anywhere in the world will never again be the same as before February 24, 2022. The methods of our grandfathers - great-grandfathers no longer work. Of course, we’d all prefer a world without war, but given the current threats and the imperial ambitions of certain individuals, the world is becoming increasingly militarized. What do you see as the trajectory of military technology development? What role will drones play?

– Technology is critical to sustaining our military’s operations. The only way we can counter this enemy is through technological capability, through synchronization and proper integration of these systems. Otherwise, nothing works.

The Russia–Ukraine war is reshaping the framework of future wars. But we shouldn’t assume that having more experience now makes us smarter than everyone else. At this moment we do have more experience, yes, but the next war will be different, with its own lessons and dynamics. It could be maneuver warfare again, but technologically enhanced; it could be armored breakthroughs, but this time in a world defined by drones.

Over these years, we’ve developed our own specific context. For other potential wars, technology must become a must-have element in warfare. But everything will depend on the environment where the fighting takes place, say, a war in Africa, Asia, or between NATO and Russia or China. Each will have to draw very different lessons from what’s happening here, because each will be a different kind of war.

– Speaking of our experience versus that of our partners, you’ve sounded rather skeptical about them. Could you elaborate on that?

– Thankfully, they’ve now fully joined the effort. Every tech-oriented unit can feel it. And our government is doing everything to support it. You can criticize the authorities, like them or not, respect them or not—but you have to face the facts and acknowledge how much the government has done to build these partnerships. It’s unprecedented. That’s not a political stance, just an observation.

From the perspective of our partners and their armed forces, they’re in the Stone Age compared to us. It’s like the Middle Ages, guys still buying tanks for hundreds of millions of dollars, and at the same time 30 drone complexes and 30 EW suites. Like the end of story.

They still haven’t grasped the core message of what’s happening here. You don’t become a technological army by buying drones, EW, or whatever. You become a technological army only if your culture is geared toward innovation.

When you achieve speed, when you plan ahead, understand how the fight will look in six months or a year, you stand up new R&D units and embed best practices. I don’t see that in some countries right now. Very few are taking constructive steps to move forward.

They’re doing generic things like beefing up air defense, electronic protection, jamming frequencies and navigation. But in terms of the culture we’ve developed here and it is a cultural phenomenon, there’s zero.

Our problem is that we recognize this culture, but as a state and as an armed force we still can’t harness these changes and turn them into a robust instrument.

– Can unmanned systems replace a soldier on the battlefield? It’s far cheaper to send robots on the assault than living people—robots cost money and life is priceless. It sounds like sci-fi, of course, but drones were once seen as science fiction, too.

– I don’t think they can. You measure the line of engagement by where your forward-most soldier stands. So soldiers are needed—at a minimum to maintain and operate all these systems.

Today we don’t have and I don’t think we’ll soon have technologies that can make those calls autonomously. We’re a long way from artificial intelligence that could control millions of drones across different climates, weather, and terrain. You still need an organizational structure for that.

Maybe someday there’ll be something like the Terminator. For now, we’re nowhere near that.

– It’s probably wrong to split drones into "good" and "bad." They’re either effective or ineffective. Still, could you name your top platforms?

– Some manufacturers are more focused on working with units and improving their solutions; some are less so. Some have more mature production and higher-quality products; sometimes it’s the opposite. But drones are divided solely by whether you can or cannot employ them on the specific axes where you operate, whether they can overcome the obstacles the enemy creates and whether they deliver results.

For example, a deep-strike platform won’t be a good fit for an infantry platoon in a brigade, whereas for a unit conducting strikes deep behind enemy lines, it’s a good drone.

So I’d say a great drone is one that ends up in the right hands, with the right infrastructure behind those hands to support them, and the right command that knows how to employ it all. That’s when it’s a top platform.

– So it’s less about the hardware and more about the people behind it?

– Absolutely.