How are UAV units fighting against Russia? Board game has been created in Ukraine that explains details of "drone war."

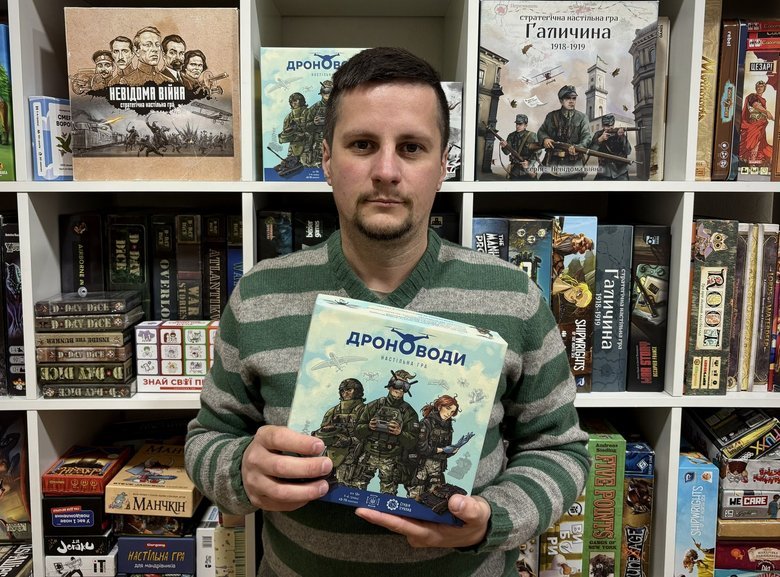

Have you heard the name "Dronovody"? No, it’s not a book or even a film, it’s a new board game, created and field-tested by Russo-Ukrainian war veteran Andrii Mochurad and his comrades-in-arms.

A game that realistically recreates the big picture and the details of the war as seen by a UAV unit’s operators.

Mochurad’s first degree is in intelligent systems and networks; his second is in cultural studies. His military training is in psychology. Andrii also has considerable experience as a military instructor. All this knowledge and skill come through in Dronovody’s well-thought-out logic, meticulous game structure, and freewheeling field humor.

Censor.NET asked Andrii Mochurad about his game and how it informs, trains, and entertains at the same time.

- In the game, using different cards, you combine seemingly unrelated things: military logistics, characters, drones in all their variety, threats, different branches of the armed forces, recruitment. And that list is far from exhaustive. Won’t a beginner’s head spin?

- It’s not a party-game level title. In the world of hobby board games, Dronovody’s rules are fairly simple. There are games many times more complex. For some, it will even be their first board game, that’s why we’re making video rules and, if needed, offering advice to newcomers via social media. You have to understand that you can’t pack a deep narrative into a primitive game. Here, we managed to create a complex product that has original mechanics, an educational component, and can serve as a tool for reflection, for veterans, for example. For others, it will be an entry point into interesting board games. The game reflects many things as they really are, with surprise threats and military humor.

- And how does that work in reality? Give an example of such a combination.

- For example, if you have a fixed-wing drone but no pilot trained to fly it, you can’t fly it or you’re very likely to crash it. In game terms, you’re essentially assembling a set of cards, like in poker. To operate a strike drone, you need something to fly, a munition, and a qualified pilot. And it’s only logical that a pilot flies the drone while a medic saves the wounded. As we designed the game, we realized it was wrong to treat a Ukrainian soldier as just a tiny token or a wooden cube. So our characters are illustrated in detail to evoke empathy and attachment, because fighters aren’t statistics, they’re people who must be protected.

- So the game is called "Dronovody." How did you choose which existing drone models to include?

- Yes, it’s "Dronovody," and we selected only Ukrainian-made UAVs that were in wide use as of 2023. We picked the drones our unit and neighboring units actually worked with. What’s more, we knew many manufacturers personally because we dealt with them, the selection is also a way to thank them for Ukrainian equipment. That’s why there are no foreign systems like FlyEye, Warmate, Puma, and the like. The game includes only Ukrainian drones, while the enemy side uses "orc" hardware.

- And did you later get any reproaches from manufacturers: "why isn’t our drone included? We want in, too"?

- Indeed, during prototype testing manufacturers were asking, "hey, can we add our drone as well?" That’s how, for example, Backfire made it into the game. But not just because the makers are our friends, we also worked with it in 2023.

Not all the drones we illustrated fit into the base game. There will definitely be expansions — more than one. If any drone manufacturer wants to reach out and is ready to help spread the word about the game in the information space, we’re open to cooperation. In other words, we’re building an entire Dronovody universe, not a one-off product.

- What knowledge does a player gain after going through your game?

- First of all, players get to know which Ukrainian drones exist and what targets are to be struck, namely, the enemy’s hardware. They also learn the difference between a multirotor and a fixed-wing drone. And, this is very important, the game features a lot of "Muscovites" hardware. Not just tanks and APCs, but their systems related to EW and ELINT, and so on. In other words, plenty of exotic, expensive equipment that counts as priority targets. Moreover, perhaps for the first time in a game, this equipment is depicted from the angle you actually see from a drone, so you can study silhouettes. A player subconsciously picks up: this is "Shipovnik," that’s "Repellent," and that one is "Krasukha." These are rare, costly models, a sign the enemy was preparing specifically for drone warfare, since much of this equipment appeared in 2017 or 2019.

- Andrii, what skills are you trying to impart to players through your game?

- Beyond familiarizing players with equipment, it’s about planning and communication. Dronovody is a cooperative game, everyone plays against the enemy and it can be used for team-building and cohesion training. The game also reflects a network-centric approach: you’ve got four units, and together you must defeat the enemy. Communicate, share resources and intelligence, and discuss the status of your specialists. In that sense, the game can be useful for training service members and platoon commanders in how to communicate and plan. Dronovody gives players an understanding of many processes that occur on the battlefield and in the army more broadly. After the game, someone who has never dealt with this won’t be starting from zero. They’ll at least grasp that military command-and-control is no easy task.

- Give an example of an operational frontline situation and how it is resolved in Dronovody.

- For example, we have a target at a given distance (the game roughly models a front line and a second line).

If we haven’t conducted reconnaissance, it will be hard to carry out a successful operation, hard to hit the target without accurate data. If enemy EW is active, that imposes an additional penalty on the dice roll. In other words, if we’re unprepared and just gambling, there’s no guarantee the die will show the needed value.

At the same time, randomness in the game is reduced if you plan actions in advance. For example, having a reconnaissance drone allows you to adjust artillery, in game terms this lets you reroll the die if the initial result doesn’t achieve a hit. Artillery in the game is represented by adjacent units or support from brigade headquarters, etc.

Thus, the game mechanics reflect the same logic: artillery firing blind is less effective than artillery supported by an adjustment drone. A drone equipped with a terminal guidance module is more effective than operating under EW and hoping for luck. An experienced pilot has a higher chance of keeping the drone intact, and so on. If personnel haven’t dug in, enemy artillery can hit them and it will be painful… Whereas a dugout will most likely keep the personnel alive.

- Am I right that players’ early mistakes resemble the errors a person makes in their first days in the military? And that through the game process, through cooperation and learning each other’s thought processes, that synergy emerges, much as it does on the front?

- Absolutely. Let me give you an example. Once, we were playing a prototype of the current game with some guys who were in Kyiv on rotation. They were combat officers. We were playing, and at some point they said to me: Andriy, we don't need a medic here, he's taking up space. It's not interesting to take the medic card. "Tell me, what's your train of thought?" "Look, I have this enemy, I've recruited 'reks' and drones, and now I'm going to take out the enemies. Why would I take a medic into my unit instead of a sapper?" "Okay. What if you have wounded soldiers? – Then I'll recruit new ones. Then he stops and adds, "No, I need a medic, because they'll kill everyone."

So the person gained experience. Without risking anyone’s life, in the game situation, they saw that this approach would result in their subordinates being killed. Ah — that decision doesn’t work. You must have the ability to evacuate wounded. In other words, without expending real resources or losing lives or equipment, Dronovody lets you work through mistakes. That’s the essence of simulation games: they provide an opportunity to talk through and learn from decisions.

- Tell us about the characters represented in Dronovody.

- The game features 12 characters. A character can be assigned to a crew, to headquarters, or to the communal trench shared by all players. The idea is simple: if the trench runs out of fighters, everyone loses because the front line holds the line. When we developed the characters, we wanted them to be more than faceless tokens; each should feel like a real person with a name and an age. We drafted biographies for every character and instructed the artist to portray them as real people. We even gave them names. There isn’t any single real person that a card is based on, each character is composite. For example, the medic was drawn using some 20 photos of different female medics, because our medic character is female. By the way, two of the 12 characters are women, so there are defenders and defenderesses. That was important to us.

We aimed for accurate depictions with no sloppy mistakes. For example, every character is shown with at least one tourniquet. The artist and I redrew those details several times so the tourniquets aren’t merely correctly illustrated, but are shown properly folded and ready for quick use in combat, not factory-perfect, but field-practical. Even the small details carry an instructional narrative.

We made sure an officer’s holster isn’t hanging like a rookie’s but is fitted and positioned correctly. Military viewers who see these illustrations will recognise people with real combat experience, people who have already lived through parts of life at the front. The images shouldn’t come across as mockery or amateurish. Enemy equipment is depicted with the same accuracy so it’s identifiable.

- You said there are 12 characters. Can you name them all?

- Because our game is about UAVs, we focused primarily on UAV operators, there are four in the game. We have a Universal Pilot who, at a basic level, can fly all drone types. Incidentally, this is a female character. All pilots can fly copters like the Mavic; we even have a dedicated Mavic card because it was the main drone in 2022.

There’s a Multirotor Pilot specializing in multirotors such as "Kazhan" and "Vampir." Another card represents a pilot who specializes in fixed-wing aircraft. The fourth pilot is an operator who specializes in FPV quadcopters. Although the controllers may look similar, operating FPV and flying a fixed-wing craft require completely different principles and skills. So we explicitly show different UAV types and, accordingly, different piloting specialists.

Of course, among the characters, there’s a Sapper and an Engineer who can program UAVs and fabricate munitions for them.

We also have a Medic who assists with personnel evacuation. In the game, after any hit a character becomes wounded rather than immediately killed. That demonstrates there’s a high chance to save personnel if you prepare and plan ahead.

Dronovody includes rear-area roles, for example, an IT specialist. As a bit of military humor, when someone is called a "specialist" in the army it’s like being called "respected" in Halychyna. So we use the title "IT specialist" rather than a colloquial label, being an IT specialist implies you can do anything, even dig a trench for cabling.

We also have a composite character called the Blogger, effectively a mix of blogger, press officer, and TV professional. This character grants bonuses if, say, they filmed a unit’s participation in an operation. We’re saying media coverage, information work, and propaganda are extremely important. For example, combat footage of UAV operations can go viral and raise the profile of the unit.

There’s also a Psychologist. He helps the unit avoid psychological burnout and assists in personnel selection. This composite character embodies functions of a recruiter, a military-psychological support specialist, and a therapist who can work with troops on burnout and PTSD.

The game includes a Logistician. In practice, this role is both a project manager and an administrator. On the front, it’s often the person who organizes processes and thereby improves logistics for the unit. In the game, logistics is the primary resource used to purchase UAVs and projects.

And of course, the Communications Specialist, can’t do without one. The Communications Specialist, like the Starlink card, grants an extra action because communication is critical to command and control.

- I read with sadness that the prototype of one of your characters was recently killed. Who was it?

- Unfortunately, I can’t say. He was a special forces soldier, and I’m not authorized to reveal his name. I can say that before the full-scale invasion he served in a special forces unit abroad. When the invasion began, he dropped everything, he was about to receive citizenship in another country and came back to Ukraine to join the fight. He fought bravely, destroyed many enemies, but sadly, he was killed. Each character in the game is, in part, a reflection of people I personally know.

Sadly, some of the people who inspired this game have been wounded or killed, and there are fewer of them with each passing month. The game itself is dedicated to my fallen comrade with whom I began developing it — Denys Karaban. He was killed in the spring of 2024. Denys was one of the brand’s co-authors; together we revived the idea of the game. Although I’ve been designing games for a long time, Dronovody was something we started together with several comrades, one of whom is also gone now... The game includes a dedication to all those who were killed. In this way, we emphasize that it’s a cultural artifact, a memory of those who gave their lives.

- Andrii, where did you personally serve? Which parts of the game are based on your own combat experience?

- The idea to create a game about drones came to me even before the full-scale invasion. I’d been carrying it since 2021, because I’ve been a veteran since 2014. Starting in 2015, I worked with UAVs, including in the combat zone. Later, I spent quite a long period as an instructor, teaching both teenagers and soldiers to fly the systems we had before the full-scale war. Back then, of course, there wasn’t such a wide variety of drones, so the concept stayed at the hypothesis stage for a while. It finally took shape as a prototype ( in the form of notes) in 2023, when I was serving in a UAV unit as its commander.

There were times when the weather grounded flights or we were ordered to stay in the trench and that’s when ideas would come! I’d pull out a notebook and jot them down. For me, at the front, it was a way to escape stress, a kind of reflection on my own experience. I also noted the funny moments from the front lines, and they’re represented in the game through the "Troubles" cards. The game contains plenty of humor and absurd situations. Soldiers say it’s truthful, painfully so, precisely because it’s truthful.

- For example?

- For example: filing a report in the wrong font means you skip a turn. Or if your unit has no drones left, all have been lost, you might draw a card saying your pilots are sent to the trenches as infantry. These are real situations! Or if your tourniquets are low-quality, a wounded soldier can’t be evacuated and dies immediately. Because how can you evacuate someone without proper tourniquets?

- Who else took part in creating the game?

- Besides Denys Karaban, whom I’ve already mentioned, at least three active servicemen were involved. I won’t name them for now. One is a senior artillery officer, another is a communications specialist. Some combat medics were also involved. In total, there was a group of about five active-duty soldiers helping to bring the idea to life. Another contributor who helped test the game is a veteran demobilized for health reasons. In addition, three avid board-gamers helped with testing, they now work with the "Ihrolad" team. So quite a few people were involved, not even counting the testers, more than ten of them. Overall, the team behind this game is large. Our designer and layout artist, Yevhen Karandash, is also a veteran, my comrade from the Aidar Battalion.

I think that among Ukrainian developments and not only Ukrainian, few board games were played more than 500 times before their release, and by such diverse focus groups. That was partly because I spent half a year in the hospital. To keep the project moving, people kept testing it, the prototype was already a well-developed version of the game. While we were preparing for release and finalizing the artwork, many people kept playing the prototype simply because it was already fun. Even before the illustrations were ready, the prototype itself was a polished product.

Why were so many veterans and active soldiers involved? Because it was easier with them. None of the veterans or servicemen needed an explanation as to why a board game about war should exist. There was no need to explain that it’s part of our informational and cultural front — part of propaganda, in the best sense of the word. Whenever I hear skepticism like, "Will the game even be popular or sell?", I can guarantee it’s coming from someone who has never fought, never served, never even gone through military training, probably not even volunteered, and is generally trying to escape from reality.

Games about World War II, The Lord of the Rings, or storming a medieval castle, aren’t they also about war? Maybe it's something else entirely?

- Here’s a not-so-glossy question: does your game address things like meat-grinder assaults, poor leadership, or other shortcomings of the military?

- It does. Dronovody includes jokes, but they’re not about positivity, they’re about reality. For example, there’s a situation where logs aren’t filled in, tags aren’t affixed. Then an inspection arrives, and you can’t attack in the next round, neither with drones nor with Support cards. You’re stuck cleaning the dugout.

That kind of ineffective management we expose and criticize — all those cards are placed in the same deck as enemy events, under the title "Troubles."

- Give an example of one of these "troubles" cards.

- In one deck, you might have several things at once, an inspection visit from high command, a faulty tourniquet, or a failed mobilization. But we present it gently. The card says, "for unknown reasons, the number of those willing to fight has dropped." That’s the "mobilization failure" card... We also have one called "order to fly in bad weather," which forces all players to check whether their drones have been damaged.

- Is it true that the profits from the game’s sales are used to train UAV pilots and purchase medical supplies for combat units?

- Yes. We can’t name every organization, but for example, at the start of the project we transferred 100,000 hryvnias to the Kolo foundation — and that was just one tranche. Right now we’re delivering a T-4 van to one of our comrades, which will go to a UAV unit. We’re also helping another raise 80,000 hryvnias for charging stations — and this kind of support is ongoing. We’ve been teaching people to fly UAVs for many years, even training wounded soldiers — both as therapy and as vocational rehabilitation. A person who has lost a limb may no longer fly missions at the front, but they can fly drones in the agricultural sector or teach others.

We stay in touch with those who assist drone pilots. We have many friends at the front, and everyone constantly needs something, spare parts, supplies, equipment.

Of course, we’re not a foundation, some organizations raise the amounts we do in just a few days, but it’s important to cultivate a culture of donating. There’s no such thing as a "small donation." Every contribution is part of the war for survival.

Sometimes it’s even easier to launch a fundraiser, someone in IT gets their salary, donates, and the goal is reached faster than through game sales. So the fundraising aspect is also part of the game’s informational mission — a kind of propaganda element that actually works.

- Finally, what do the first buyers say? What positives do they highlight?

- You can read it in the reviews. Everyone notes the same positives — the game has depth and replayability. There are multiple ways to play, multiple paths to take. After playing once, people want to play again to explore what other possibilities it offers.

Some players have highlighted Dronovody’s tournament potential as a major plus. We deliberately designed the mechanics so competitions could be held for both young people and adults. Сompetition boosts engagement.

Another point the military appreciates: the game is highly realistic. It can be used as a kind of process simulator. People really like that.

- What about drawbacks?

- Overall, players say the game is so well made that the downsides can be counted on one hand. Board-game enthusiasts have asked for alternative dice or a premium version of the player boards. But between premium build and affordability, we chose to keep the price accessible for a wide audience. For connoisseurs and collectors, we produce premium editions that can be won at charity auctions raising funds for the military. Certain accessories will be available for purchase on our website or via social media.

- So where and how can people buy the game?

The game is already available in stores, and you can also buy it on our website, where you will find video rules, information about events and additions. You can also contact us through social media.

We’re very approachable, and we’re ready to help schools and other institutions run tournaments or events. We also assist newcomers with the rules — just message us directly.

No other publisher or developer offers this level of support; for us it’s primarily about values and spreading the culture of drone operations.

Yevhen Kuzmenko, Censor.NET