Impressions from fighting in Kursk region? Like I’d been on retreat in hell – Yevhen Makatsoba

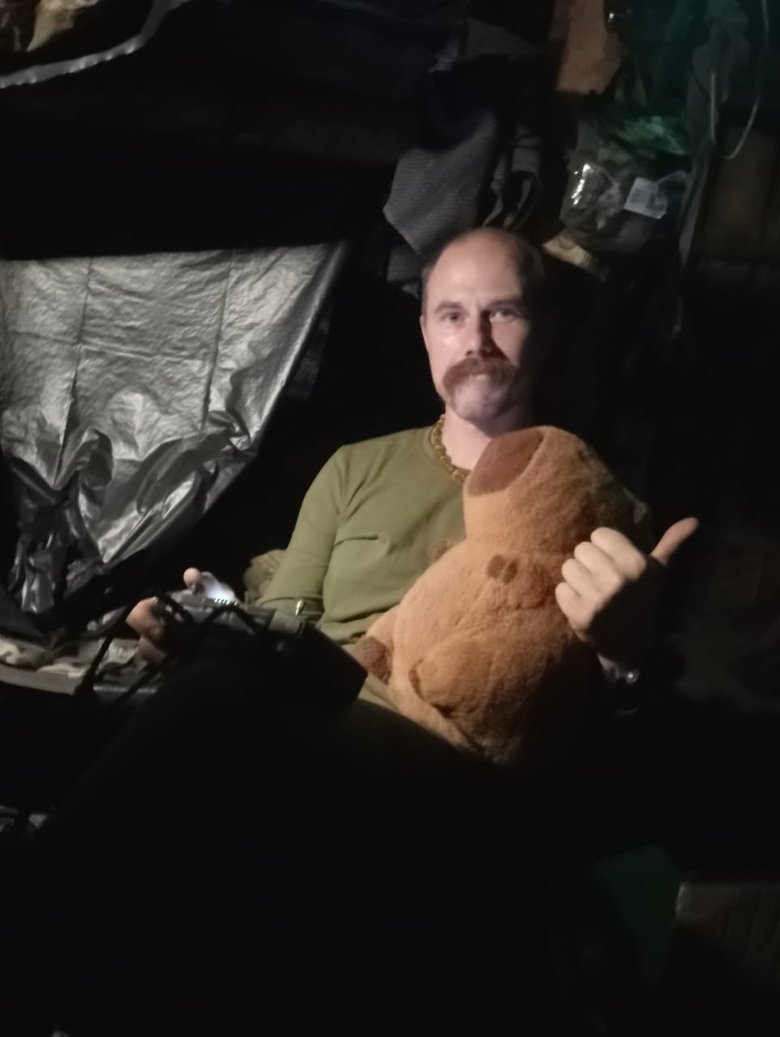

Yevhen Makatsoba (Kobzar), a craftsman of traditional folk instruments, has been in the military for a little over a year, though his combat record spans only a few months. During that time, serving as an infantryman with the 78th Separate Airborne Assault Brigade, he sustained an arm injury and what he called "unforgettable impressions" from fighting Koreans in the Kursk region.

In an interview with Censor.NET, the serviceman spoke about his combat path, what he described as the state’s unfair treatment of wounded soldiers, and his new role as a UAV operator.

ON NEW YEAR’S EVE 2025, I WAS DIGGING TRENCHES

- Yevhen, you are among those who believed that music and musical instruments also contributed to Russia’s defeat. That is why you joined the military in 2024.

- I made banduras and kobzas and ran workshops on making wooden toys at the "Ukrainian Village" ethnographic complex. My workshop is still there, with a sign saying it is temporarily closed because the craftsman is serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. I am not the only one mobilized from "Ukrainian Village." Our pottery master, Sashko Yarovyi, and our museum worker were mobilized as well. In other words, there are fewer and fewer "free" men left.

- How did I end up in the military?

- On November 17, 2024, I was walking to my garage with a cordless screwdriver when I ran into the Territorial Center of Recruitment (TCR). They stopped me to check my registration documents and took me with them. I did not resist, because I knew it would happen sooner or later, but I had not gone on my own because I genuinely believed my banduras were a powerful weapon.

The brigade I was assigned to was the 78th. My friend Yura Samaniuk (Thirteenth) served there and was killed near Bakhmut. There was no doubt that I had to go. Still carrying that same screwdriver, I was taken to the military medical commission (MMC) in Obolon. Everything there happened quickly, and then they said we would be taken to a central point to sign the paperwork, and only after that, sent home. They said this in order to actually take us to DVRZ. Fortunately, they did not take our phones at the time, so I was able to call my wife and ask her to bring me the necessary things. By morning, I was already heading toward Zhytomyr to join the 78th Brigade.

We were pulled out of Basic Combined Arms Training a week early, so on New Year’s Eve, I was digging a trench.

- Were you sent to the Kursk region right away?

- Yes, I miraculously got out of there.

- Tell us about your combat experience in the Kursk region.

- My impressions of the fighting in the Kursk region? Like I’d been on a retreat in hell. When we moved in, Koreans were advancing on us. To be fair, I never saw them alive up close. There were bodies everywhere, and you’re sitting in a position that enemy drones watch day and night.

While their infantry was crawling forward, our drone operators were eliminating them, but some still managed to reach our positions and open fire. Naturally, you start returning fire.

This is what it looked like. We were told to move into a position and hold the line. The position was a cluster of half-collapsed clay houses. I don’t know how the Russians live there, but there were only three or four cellars in the entire hamlet. That meant only three or four houses were even usable for fighting. But in every cellar there was either one of ours or one of theirs — KIA.

- So you held your defense.

- We were told we would be covered. But when we arrived, the question was where that coverage was. The houses were partially collapsed, and getting in and out took time. Drones detect the slightest movement, so most of the time we had to stay hidden.

And how are you supposed to hold the defense when we were under constant fire and exposed to some kind of gases – to the point that we were vomiting afterward? We moved into this position and realized that because the roof was destroyed, the Russians could see us. I started trying to patch it up at least somehow; two other comrades couldn’t do it because of their health conditions. We dug a sort of burrow so we could hide in that chaos. Everything was mixed together there: our ammunition, food, slate, bricks, boards, clay, metal... And that’s how we held the line.

We didn't want to eat as much as we wanted to drink. They didn't bring us food, water, or ammunition. We could only get clean snow when we made quick runs out of the hut.

- What were your impressions of your first time in position, your first battle?

- Simply put, the moment we drove into the position, enemy drones immediately went to work on us.

OUR MISSION WAS EXTREMELY DANGEROUS, BUT WE CAME THROUGH UNHARMED. THOSE WHO REFUSED TO GO — ALL OF THEM WERE WOUNDED

- When and how were you wounded?

- On February 22–23, that was when the freeze hit. On paper, I’m listed as lightly wounded, but in reality, we were holding a position, a half-collapsed shack, when a 120mm mortar round hit it. When those Korean bastards were pushing in, I told my buddy: "At least keep loading magazines for me." The magazines were gone in seconds. My comrade Dmytro Postyliakov was killed then; he remained under the rubble because it was impossible to get him out. (He was an orphan and unmarried. The only relative he had left was an uncle.)

When they realized they were taking fire, they started pulling back. The VAB we rode in burned out. The drivers made it back on foot — luckily, they were unharmed, because drivers are often burned to death in FPV strikes.

And the same thing happened when they came to evacuate us… We assigned roles. There was one severely wounded man, he had lost an arm and a leg and couldn’t see. He spent the whole night on a sleeping mat on the snow, in freezing conditions. When the evac finally arrived, I helped load him. My right arm was injured, so I had to take the left side so I could pull him in with my left hand. I ran up to the VAB, and an FPV drone struck. We were supposed to start moving out. I climbed in with my rifle, and the driver yelled: "Call the others." I looked out, and they were all hiding in the bushes. The guys were afraid another strike was coming, and that happens often. I jumped out to shout for them, leaving my rifle in the vehicle. The VAB drove about 200 meters, and another FPV drone hit it; that’s when the vehicle finally went up in flames. Thanks to the drivers, who knew the route, we got out on foot.

- Were you able to save that severely wounded man?

- No. We carried him into a dugout. He asked to be put on a bunk because he was freezing. That was probably his last wish. He died afterward. If the evac vehicle hadn’t burned out, he would have been saved.

- What was your impression of the Koreans? Everyone talks about how many of them there were, and about them seeming almost zombified.

- There was an incident before that. Over the radio, we were told to take single-use launchers and grenades to a neighboring position because a Korean was holed up in a cellar there. None of our guys wanted to go. I volunteered, along with one other man, and we went together.

It was straight out of the movie Forrest Gump: we’re running across a snow-covered field, and mines are landing behind us. I understand why we weren’t killed; the rounds were landing at an angle, so all the fragments flew forward. If they’d landed flat, they would have mowed us down. And when a mortar round lands about 50 meters from you, the adrenaline hits so hard that both your helmet and your ammo suddenly feel light, you don’t even understand how you managed it.

Long story short, we brought the single-use launchers and grenades to the position. One b#stard got in there and seemed to have dug himself in. They threw two grenades at him and he was still firing back. Then they tossed in the grenade we’d brought and that’s how they finished him off. When we got back to our position, all the guys were wounded or otherwise injured one way or another, a mortar round had hit there. The thing is, our mission was extremely dangerous, but we came through unhurt, while everyone who didn’t want to go on the mission ended up hurt.

The assault group we helped was ordered to move on to the next task, but drones and FPVs were constantly overhead. They were told to start moving out slowly. They made it to a nearby shed when they were hit hard; three were wounded immediately. They had to pull back. My point is that when a commander gives orders without being on the ground and assessing the situation, it can end badly. How people on the front line are treated matters in everything.

- Still, why do you think the drones and support you were promised didn't show up?

- We had our drones, but we didn’t have "Vampirs" to drop food or ammunition to us. After I was wounded, I spoke with drone operators who warmed me up and gave me tea. They handled reconnaissance and payload drops. On the approaches, they cleared out some of the enemy infantry that was pushing toward us.

Our artillery was there too. I understand how it works now: we report the direction the enemy artillery is coming from, the distance, the caliber. And then counteraction should follow, with drones and artillery. In 30–40% of cases, it helped, and their guns fell silent. But when the guns went quiet, drones would fly in. And sometimes it was all at once — drones, artillery, MLRS, and even guided aerial bombs. Aircraft and a tank were also engaging us.

I WAS REMOVED FROM THE UNIT'S STAFFING LIST ALMOST IMMEDIATELY AFTER BEING WOUNDED. IT FELT EXTREMELY DEMOTIVATING

- Let’s go back to your injury. What wounds did you suffer, and what happened afterward?

- A comrade next to me was killed, and I was badly concussed and my arm was torn up. We left the position right away, but as I said, we couldn’t get out of there for a long time. We couldn’t leave the second line for a long time either — there was shelling and there were injuries there as well. During that time, my arm started to fester.

In Sumy, doctors drained the pus and said that if we’d lost another two or three days, they might have had to amputate my arm at the elbow.

- When were you removed from the unit’s staffing list? Was it while you were still being treated?

- I was removed from my unit’s staffing list almost immediately — two weeks after the injury (which is illegal) — but I only found out months later. The feeling was, of course, awful and deeply demotivating. You realize the enemy isn’t only outside, but inside as well, as Petliura said. I had to swallow it and go back to fighting.

- How did you get through that period while you were off the unit roster?

- At the permanent station (PS) near Zhytomyr, I was waiting for an MMC to confirm that I was no longer fit to serve in the Air Assault Forces. Even there, there were sometimes problems with getting treatment: you have to file a lot of written requests, and some of them get rejected. I managed to get treatment twice, two weeks each time. I suspect those hurdles were put in place to save money. They supposedly secured my treatment payments, but I still haven’t seen them.

If this is how commanders treat their own people, how do they expect to win this war?.. It ends up looking like a Soviet Ukrainian army fighting a Soviet Russian army. That is profoundly demotivating.

So I kept waiting for the MMC. Then my commander suggested I try working with UAVs. I agreed, because I was going out of my mind there at the PS with no money. And since September, I’ve been fighting near Sumy.

- What pay were you getting then?

- About 800 hryvnias. Some months, even that didn’t come.

- So now you’re doing reconnaissance using Mavics and Matrices. How do you feel in this new role?

- Working with UAVs is more interesting; you can genuinely help eliminate the enemy on a large scale. It’s important to be the first to find their drone operators’ positions; otherwise, they’ll pinpoint you too, and it turns into a cycle of mutual elimination. There have been times when we found their drone position and smashed it.

In Sumy region, where I am now, the infantry is very active. Sometimes MLRS are used, and very rarely a tank engages. It’s not the same hell as it was in the Kursk region.

- Given your intense combat experience, your injury, and the period you then spent in limbo, what are your thoughts on the low level of mobilization?

- I don’t judge people for not wanting to go and fight. Even if I had known what awaited me, I still wouldn’t have dodged it, because I understand that Russia is our enemy and I know what awaits us in the event of occupation. We have ended up between a rock and a hard place — between the Russians and a state that often treats its soldiers unfairly.

Society really has taken a step back from the war. But it’s a contradictory and complicated answer. In the end, I have a wife and children — why should they be under constant strain because of the war? When there are no strikes nearby, life goes on.

Olha Skorokhod, Censor.NET