"Bullet went through my leg and shattered bone in my son’s leg as I carried him in my arms. Wound was so large that doctor could push his hand straight through it."

Our children are injured not only on Ukrainian soil. The son of a woman from Cherkasy was wounded in Syria before he had even turned one year old. The woman ended up in the country at the urging of her husband, who wanted to teach children. Most Ukrainian women arrived in Syria from occupied Crimea, fleeing Russian occupiers. In the majority of cases, they were Crimean Tatar families.

Wounded children evoke an overwhelming sense of pain and personal helplessness because there is nothing you can do to prevent it from happening. And when a child suffers a gunshot wound as a mother tries to save her baby, to evacuate or carry the child out from under fire, the horror is felt physically, through the skin. This is precisely such a story. While watching the documentary "10 Lost Years" by journalist Iryna Sampan, I discovered that dozens of Ukrainian families had ended up being held hostage in Syria. Most of them were Crimean Tatar families who fled the Russian occupiers from annexed Crimea in 2014.

Arriving in Syria with no idea of what lay ahead, they later found themselves caught in active hostilities. Men were killed, while women were left rightless, invisible, and homeless. For a long time, their voices went unheard. But eventually, a woman emerged who managed to reach the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Main Intelligence Directorate (HUR), and the president. In 2020, a special operation to bring Ukrainian women back home was launched. The first families were brought home in late 2021. However, even during the full-scale war, the special group continued rescuing Ukrainian women. In 2025, HUR officers extracted the last Ukrainian citizen who had remained in a refugee camp under horrific conditions. Prior to that, in the autumn of 2024, Inna from Cherkasy was brought back home along with her son, whom she had given birth to in Syria and who had been severely wounded when his mother attempted to flee militants. The boy’s leg was not properly treated at the time. Once in Ukraine, he underwent a complex surgery. More operations will be required. Yet Inna, who lost her husband, her daughter, and later her second husband, the father of her son, while in Syria, is prepared to do everything for her child.

"A SHELL HIT OUR HOUSE, AND WE WERE BURIED IN THE BASEMENT. WHEN THEY DUG ME OUT, I WAS BLUE AND BARELY BREATHING. MY DAUGHTER WAS KILLED."

"My first husband was an elementary school teacher. At one point, he was even recognized as the teacher of the year in the region where he worked. His parents were also teachers, and over time, both his mother and father became school principals. My parents are teachers as well," says 41-year-old Inna Dobrovolska. "My husband dreamed of creating something for children who had no opportunity to receive a proper education, to do something meaningful in places where it is most difficult. When his nephew showed him a video of children in Syria who had been left orphaned, he saw their suffering and became determined to help them in some way. He was not certain it would be a school. He simply wanted to go there and help children. How exactly, where, and in what form, those were details we planned to figure out on the ground."

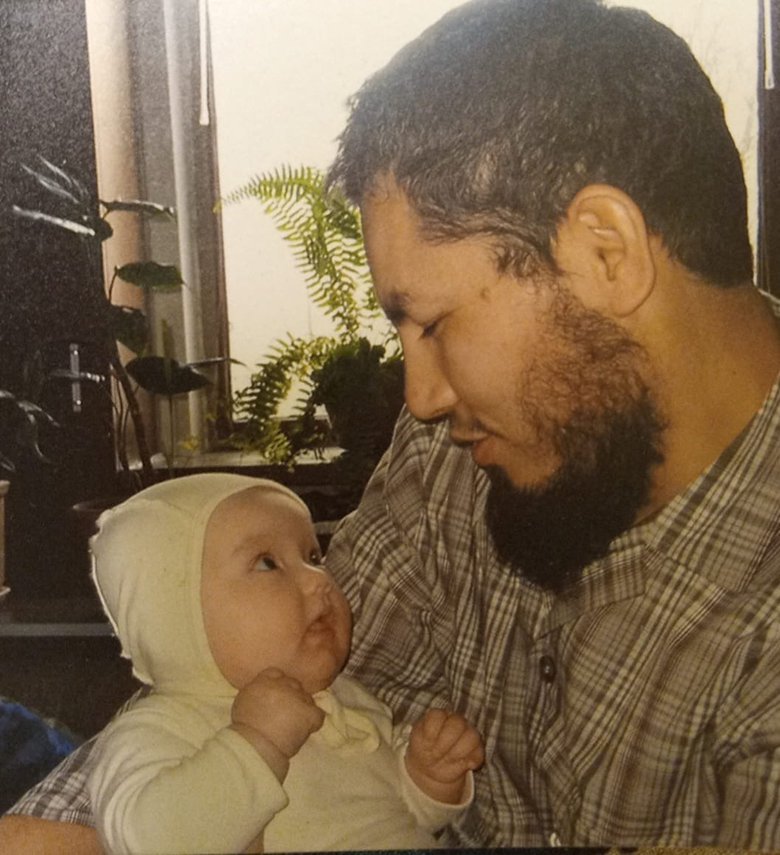

The family from Cherkasy moved to Syria in February 2014. At that time, Inna and her husband were already raising a daughter. She was one year and four months old.

"By February 10, we were already in Syria, in the city of Raqqa," Inna continues. "Unrest had begun there, and there was effectively no state anymore. The war moved from Syria into Iraq. In the city where we ended up, there were no schools at all — they had been bombed. Assad deliberately struck hospitals and schools, just as Putin does in Ukraine. They share the same ideology. In March, my husband renovated a building that had nothing but walls and a ceiling and opened a school there. We were allowed to take desks from state schools. We had to print textbooks ourselves because books were extremely difficult to find. A printer was brought in from Turkey, and that is how the textbooks were produced. Teachers of physics, mathematics, Russian language and literature, physical education, and Arabic were found." Children began attending the school. Many were Syrians. Later, Russian-speaking students appeared. After the occupation of Crimea, people from Crimea began arriving in Syria, fleeing the Russians. Our children also joined the school. When I learned that Russia had taken Crimea from Ukraine, I was utterly shocked. I could not even imagine that war could begin on my own land.

That is how we lived for eight months. During that time, we purchased our own house, which my husband immediately registered in my name. Then the war began returning to Syrian territory. War always returns to where it started, I understand that clearly now. The United States began assisting the Kurds, who pushed Assad’s forces out of Iraq. Aircraft appeared. They would fly in, drop bombs, and fly out. My husband was driving, buying supplies for the school. A bomb fell nearby. A fragment struck him in the head. The bone was not penetrated, but he bled out…

My daughter and I were left alone. I desperately wanted to return home. A foreign country, a foreign language, and a two-year-old child in my arms, how was I supposed to survive? My mother contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but was told that no help could be provided because no laws effectively functioned on Syrian territory. They suggested that I somehow reach Turkey, from where assistance with returning home might be possible. But leaving Syrian-controlled areas was almost impossible. Those who attempted to leave were caught by Assad’s forces and imprisoned. I tried to find out how it might be possible to get out, but I was told, "Then we will take your child, and you will never know where the child is." I was afraid to even try. Some people I knew managed to reach Turkey, but I did not risk taking their route, because most of those who tried were eventually caught.

When my daughter turned five, I remarried. My second husband was born in Moldova. His father was Ukrainian, as were his grandparents, while his mother was Moldovan. When he started first grade, his parents were offered work in northern Russia, where they lived for many years. He later ended up in Syria after being offered a job there. When I was left on my own, he would come to help me. The house where my daughter and I lived had four rooms. Nearby, there was a large generator; we paid for electricity for two to three hours a day to manage basic household chores. At one point, neighbors diverted our amperage to themselves. During that period, a woman with two children was living with me. She had just given birth, and I helped care for the newborn. We kept warm using a UFO heater lamp. Then the electricity disappeared and did not come back. I called him. He came and helped sort things out.

When Kurdish forces advanced to the outskirts of our city, he proposed that we get married. "You are alone with a child, without a husband. If the city is encircled, there will be no one even to bring you water," he told me. He was a kind man and loved children. I agreed. We got married. I became pregnant. In October 2018, I was five months pregnant when a shell hit our house. We were in the basement of our home. The house collapsed onto the basement. My daughter and I were buried under small stones and debris. When they dug me out, I was blue and barely breathing. My daughter was not breathing at all. She died. For three days, my unborn son did not move inside me. A woman I knew and her two children were also in the basement with us, we saw each other often, their family frequently came to my place, and the children had grown attached to me. That woman was also buried and killed. My husband was in an adjacent room in the basement. He was not injured. Someone took the daughter of that woman away, and as soon as I was dug out, I grabbed my friend’s son and held him in my arms. The skin on his head had split open down to the skull. The bone was visible. For two days, I went from doctor to doctor, begging them to stitch the wound. They refused, saying it was too contaminated and needed to be cleaned first. Later, I also found the daughter of my deceased friend. Those children stayed with me until I gave birth. Then their grandmother appeared and took them away. I still remember how the children screamed, how they did not want to leave me…

My son was born while we were on the run. Our house, or what remained of it, was constantly shelled by Kurdish forces, so we kept searching for safer shelters. At that time, there were many abandoned houses and apartments in the city. On February 3, we spent the night in yet another abandoned room. That is where my labor began. My son was born on the same day as my mother. I did not expect it to happen that day. The necessary items were not within reach, even though I had prepared them, they were tucked away somewhere deep in the car. There were scissors there as well. As a result, the umbilical cord was cut with a blunt knife. The delivery was assisted by a woman I knew. She was later killed.

My son was born extremely small, weighing less than two kilograms. This can be explained by the fact that I ate very poorly during the pregnancy. When the city came under siege, our entire diet consisted of rice, bulgur, and pasta. There was nothing else. My husband laughed when I said, "It can’t be that there is nothing green here. There must be some leaves or grass somewhere." I was ready to chew grass. I desperately wanted something green. So he took me to a park so I could see for myself that everything there was yellow and dry. And that was indeed the case.

The scales we used to weigh my son did not show an exact weight. A few days later, a doctor examined the newborn. He said that based on the signs, everything seemed fine, the baby was just very small.

"A KILOGRAM OF SUGAR COSTS ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS"

"We moved to another city, where we lived for almost a year without war," Inna continues. "Then hunger returned. I cooked whatever I could find outside, grass, some kind of mushrooms. My husband brought bran, but it was nothing but wheat husks. The children ate porridge made from it and passed blood. There was no other food. To give you a sense of it: a kilogram of sugar in the city cost one hundred dollars at the time. Finding nettles or any other greenery felt like a stroke of luck. I would taste whatever I found. If it seemed edible, I could stew it or make a salad. It helped that we had some oil and vinegar, so at least we could season what we found."

At some point, all of us were driven to the town of Baghuz to dig trenches. We lived there as well, in the very trenches we had dug. That was where my son and I were wounded. We were moving to another field with trees. I was carrying my son, who was not yet a year old, in front of me because gunfire was coming from behind. On my back, I was hauling bags, a backpack, and some pots. I was shot. The bullet passed through me and struck my son as well, hitting his leg. I tucked his head against my chest, while his legs hung between my legs. The bullet pierced my leg and then went through his. The doctor I ran to immediately, there were doctors in those fields, refused to stitch my son’s wound out of fear. He stopped the bleeding but would not do anything else. He was an Arab man with large hands. He was able to push his palm through the wound in my son’s leg.

My husband found another doctor. We could not leave that area — everyone who tried to do so was shot. A week later, Americans arrived in those fields together with Kurdish forces. They offered that anyone who wanted to go home could leave with them. They said they would evacuate all those willing to a refugee camp, from where each country would retrieve its own citizens. They told us to submit applications through the Red Cross and that we would be taken out. I agreed. Many people left with me. When we arrived at the camp, the first thing I did was find the Red Cross and submit the required applications. There, I met other Ukrainian women who had also become hostages to the situation.

- Where was your husband at that time?

- When we were taken from the fields, my husband left together with us. But he was detained and sent to prison. Only women and children were transported to the camp. Some time later, I was told that my husband had died in prison…

"THE TORN PIECE OF FLESH FROM MY LEG WAS ATTEMPTED TO BE SEWN BACK WITHOUT ANESTHESIA, WHILE I WAS AWAKE, BUT INFECTION SET IN AND IT FELL OFF"

Inna and her son spent six years in refugee camps in Syria. They lived for two years in the al-Hol camp, and then for more than three years in the Roj camp. There, the woman taught children mathematics, even though in Ukraine she had worked as an international tourism manager, a translator, and an economist.

"At the camp, a doctor stitched my son’s wound, gave me iodine, and showed me how to change the dressings," Inna continues. "I constantly washed and ironed the bandages I used to wrap my son’s leg. Doctors began arriving at the camp in specially equipped vehicles, and there was even an X-ray machine. Finally, an image of the leg was taken. I saw that the tibia had been shattered by two centimeters. We were given a splint to immobilize the leg. They also issued calcium and vitamins. My son liked the calcium. In addition, he was constantly on breast milk. Over time, everything healed, and the bone recovered."

During that period, we watched the camp being developed: utilities were installed, and water was brought in. Once construction was completed, the camp was divided into two sections. One was for Syrian refugees. Families there were given tents, and they built entire courtyards around them. They were allowed to have phones. Orphaned children were placed in children’s homes. Hospitals were also built, two of them. One of the hospitals was Syrian-run, while the other was built by Norwegians, large and well-equipped. Doctors there spoke English. My son and I sought medical care at both. In the other section of the camp, foreigners were held. Later, a hospital was also built in our camp. In the sector for foreigners, everything was prohibited: phones were banned, and families were not allowed to live together. Over time, a market opened. We began negotiating with vendors to bring in books, and later they quietly passed along phones as well. At the hospital that was built for us, my son was examined, and X-rays were taken. His legs were the same length. It seemed that everything was over, and the bone had healed. My son began to walk and run.

- You have spoken only about your son’s wound. But you were injured as well…

- The bullet tore a piece of skin and muscle out of my leg, but did not hit the bone. It was painful for me to walk. They tried to stitch that torn-off piece back on, without anesthesia, while I was fully conscious. But inflammation set in. And it all came off again. I tightly taped the wound with medical adhesive, and over time, it healed. A terrible scar remained, but the leg functions. I never even showed my leg to the doctors in the camp. The priority was treating my son and securing our return home.

In late 2020 and early 2021, another woman appeared in this story, a citizen of the European Union whose niece from annexed Crimea had also ended up in Syria and later in a horrific refugee camp. The Ukrainian women held there were known to authorities; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had their names. However, there was no solution for how to extract them. Flights to Syria were not operating, and there was no way to enter a country whose leadership was not recognized. But the same woman, Fatima Boiko, reached out to the leadership of Ukraine’s Main Intelligence Directorate. That is when the situation began to move.

"Fatima, as an EU citizen, received more substantive responses, not formal replies or dismissals, but explanations of why it was impossible to send a plane for us and why support from intelligence services was required," Inna continues. "Fatima stayed in contact with all of us who held Ukrainian citizenship and were in the refugee camps. Several times, we recorded and sent her videos appealing for our return home and documenting the conditions in which we were living with our children."

When my son was two years old, in the summer heat, there was neither electricity nor water in the Roj camp. One afternoon, he fell asleep, his temperature spiked, and he began having seizures that lasted for 20 minutes. When the seizures stopped, I wrapped him in a towel and ran to the hospital. Kurdish doctors looked at him in my arms and said, "Go bury him, he is dead." He was completely motionless. I left without any hope. Then I heard a woman speaking English. I held my son out to her and begged, "Please do something." She listened to him and immediately began acting. They administered injections, cooled him down, and turned on the air conditioner. He came to. For several days afterward, he could not speak or walk and only lay there. From that point on, my son began having seizures. At night, he would sometimes stop breathing. When he turned four years old, all of this stopped.

- But was he able to walk normally?

- When my son was three, after we were transferred to the Roj camp, he began walking on the toes of his injured leg. I sought medical help, and we were even taken to the city under guard. There were three or four men armed with rifles accompanying my son and me. I sat in the waiting line with them sitting beside me. They did not allow us to even walk down the corridor. Orthopedists and surgeons examined my son, and they even performed a CT scan. The doctor said he could operate under general anesthesia, but gave no guarantee that my son would tolerate anesthesia due to his seizures. After surgery, he would have needed regular physiotherapy, without which there would be no result. The doctor asked me, "Will you be able to take him?" That meant allocating guards and a vehicle every day. The guards said, "No, that is prohibited here." The doctor explained that a mother could not rehabilitate the leg on her own — only device-based rehabilitation would help. "If I cut now and the procedures are not done afterward, it could become even worse," the doctor explained. We were taken for consultations several times… But I never dared to agree to surgery there. I waited for our deportation and return home, while watching his condition worsen.

To extract Ukrainian women from Syria, the Main Intelligence Directorate developed a special operation and deployed its best intelligence officers. In late 2021, the first large families of Ukrainian citizens were taken out from a refugee camp — one mother had seven children, another had four.

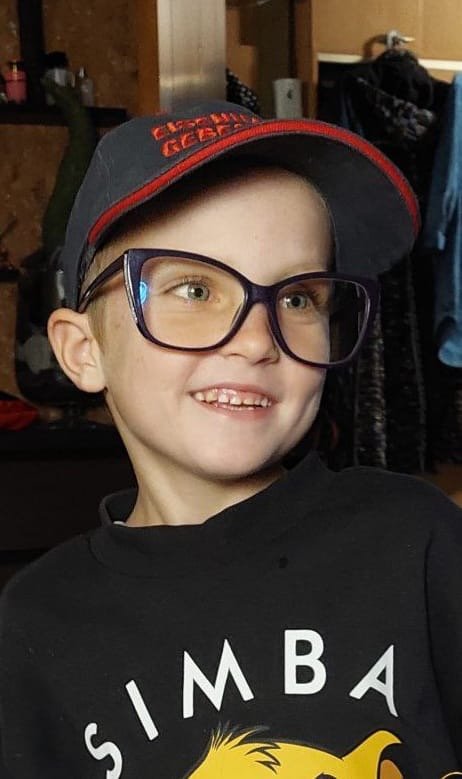

"The next time there was such an opportunity, they took women who had two children," Inna recalls. "Of course, I wanted to go home as well. I said my son was wounded, that he walked poorly and needed medical care, but there was an established order. I was terrified that it would be too late for treatment by the time we were taken out. I even asked: take my son alone, my mother will meet him, and I will wait for my turn. But HUR set a queue and adhered to it." Perhaps this order had been agreed upon with those who were holding us… After the large families were taken out, only my son and I and two women without children remained in the camp. We were evacuated on September 21, 2024.

When we returned home and sought medical care, doctors determined that the difference in leg length was already more than two centimeters. The foot of the injured leg was smaller and deformed compared to the healthy one. It was a complex case. Doctors in Cherkasy were unable to help us and referred us to Kyiv. I did not know whom to contact or where to go there. However, when I studied at the Cherkasy Physics and Mathematics Lyceum, one of my friends always said she would become a doctor, and she did. She has two children, and her older son has cerebral palsy. She had taken him to specialists in Kyiv many times. I asked her to recommend a doctor. That is how we ended up at the capital’s Institute of Orthopedics and Traumatology.

While we were waiting for our consultation, we handled the paperwork. In Syria, my backpack had been stolen — it contained food, documents, and rags I used instead of diapers. To obtain my son’s birth certificate, I had to go through court proceedings and a DNA test. At that time, my son was also given a new name, chosen by my mother. At birth, my late husband had named him Abdurakhman. When we returned, my mother said she did not like the name. I asked her to choose another one. She offered three options, one of which was Kamran. That is the name we chose.

After receiving the birth certificate last summer, we went to Kyiv for a consultation. The doctor said that during the injury, the bullet had torn away a portion of the muscle responsible for flexing the foot. My son wanted to walk, but he began limping because he could not bend his foot. The wound site was torn and had healed with adhesions that compressed the muscle and nerve. First, the bones needed to be corrected, then the muscles, and only after that could attention turn to the nerve.

During the surgery performed on November 25 last year, the leg was rotated by 90 degrees. There was no need to secure the bone with plates. Now, through rehabilitation, we are trying to stretch the damaged tendon.

Everything seemed to be going well. It felt as though the most dangerous part was already behind us. But a few days ago, while on her way to work, Inna fell and broke her leg. She spent a week in the hospital because the fractured bones had to be fixed with a plate. For three months, she is not allowed to put weight on the leg.

"While I was away, no exercises were done with Kamran. Everyone was also busy traveling to the hospital to see me," Inna sighs. "And when my aunt took my son for a follow-up consultation last week, the doctor said he was not satisfied with the results. We need to work more actively and rehabilitate the leg. Even before I fell, I had already submitted my resignation, because I cannot give my son as much attention as he needs."

- Do you think about Syria and what you went through there? How has it affected you?

- When I was a child, my mother once quoted a scientist’s words to me: if you cannot change the situation, change your attitude toward it. I could not independently change everything that was happening to me. It was important for me to remain psychologically healthy. Even now, I do not allow my emotions to come to the surface…

My grandfather also taught me a great deal. We were very close. He was a highly intelligent man who developed various devices and held many patents for his own inventions. Whenever there were problems, we would always consult with him. He never gave direct answers, instead, he forced you to think. And once you reached a conclusion, he made you consider the opposing viewpoint before making a choice. When I was finishing school, he was diagnosed with cancer. He underwent treatment, but a blood clot broke loose and he died. I visited him while he was ill and could not come to terms with it. During that time, he once told me: "You will face many difficult trials in your life, when you will not know what to do. In such situations, your head must remain cold, because decisions have to be made, it is impossible to run away from problems. And for that, you must learn emotional withdrawal." That is how I live now.

I constantly remember my daughter. There is not a single day or hour when I forget that she existed. But I do not allow myself to sink into grief. In the camp, when things became unbearable, and thoughts overwhelmed me, when I worried about what would happen to my son if something happened to me, I sometimes felt I was losing my mind. At those moments, I forbade myself from thinking about everything that had happened to me. I kept finding work for myself: ironing, cleaning, building, just to keep busy and not think.

- What was your daughter’s name?

- Kamila. My husband chose the name when I was still pregnant. We wanted children very much, but I couldn’t get pregnant for a long time. Every time my period was late, we would get excited, maybe I was pregnant. But it never happened. At some point, I even made peace with the idea that I couldn’t have children. But my husband sensed that something had changed. One day, he brought home a test: "You need to take it." "Are you serious?" I was genuinely surprised. "I can tell you’re pregnant," he said. And he was right.

Syria became a major school of survival for me. I had always been afraid of situations where I might not have enough air. I was afraid of suffocating. When I was buried under debris, I realized it was not as frightening as I had thought. When you don’t have enough air, you simply fall asleep. Once you go through that, you stop being afraid of many things.

And now, our country has no electricity and no communications. Many people panic over it, but I know what to do. Syria has terrifying winds. We lived in tents that were sometimes blown away. Once there was a brutal downpour, and I woke up because the tent collapsed onto me. I held it up. The cold rain was pounding down. The wind was dragging me along with the edge of the tent I was gripping. And I understood: if I let go, if I give up, the tent will fly off and my son will be left out in the rain. So I hung onto that edge of the tent. I held on, waiting for a lull so I could secure that "roof" over our heads. And I did. After everything I have lived through, I am far less afraid of the future.

When the full-scale war in Ukraine began, I was in a refugee camp. We had a TV because a generator worked from time to time. Ukrainian channels were hard to find, but I immediately refused to watch any Russian channels and watched English-language ones instead. We argued with Russians who were also in the camp. There is a big difference between our peoples. Even Dagestanis and Chechens - they are all thoroughly shaped by propaganda. Everyone is afraid to say, do, or write anything extra.

After I returned to Ukraine, a staff member of a UK human rights service contacted me. We spoke by video call. She asked me for contact details for Russians who remain in those camps - Russia does not take them back. She wanted to speak with them. But as far as I know, they all refused. They are afraid of what will happen if Russia finds out about the conversation. Even those who managed to leave the camp, paid money, and ended up in pro-Turkish regions of the country - they also stay silent. I will say more. I know that those who managed to return to Russia via Turkey were imprisoned at home - some for 15 years, some for 12, and some received 25-year terms. And these are women who have children! The children were handed over either to relatives or to orphanages.

You know, we, the women who, for various reasons, ended up in Syria, were invisible for many years. And our circumstances, the situations each of us found ourselves in, were based solely on our words. There is virtually no evidence of what we went through and why. But by making a film about us, Iryna has proven our truth and given us legitimacy. For each of us, this is extremely important.

The film by Iryna Sampan is available to watch via the link

The women from Crimea who returned to Ukraine after so many years of hardship strongly believe they will be able to go back home to the peninsula after Ukraine’s victory in the war. I am very glad to be home again, with my family, and to be able to focus on my son’s health. And I will do everything to ensure he can walk normally.

Kamran is a winner at heart. And his victories in sports prove it.

P.S. During the Kyiv premiere of the film "10 Lost Years," a fundraiser was organized to support Kamran’s treatment. After Inna was injured, all the money collected by that time was transferred to the family.

Violetta Kirtoka, Censor. NET