Ruslan Maryshev, Commander of 95th Airborne Brigade: "Deputy gave me pack of M&M’s and said: "Commander, stay in cover today so you don’t get killed on your birthday."

In February–March 2022, this officer served as a battalion commander in another airborne brigade and was deployed to Izium with part of his unit. In an interview, Ruslan spoke about the week when the Russians destroyed the city—and how it is still being battered to this day.

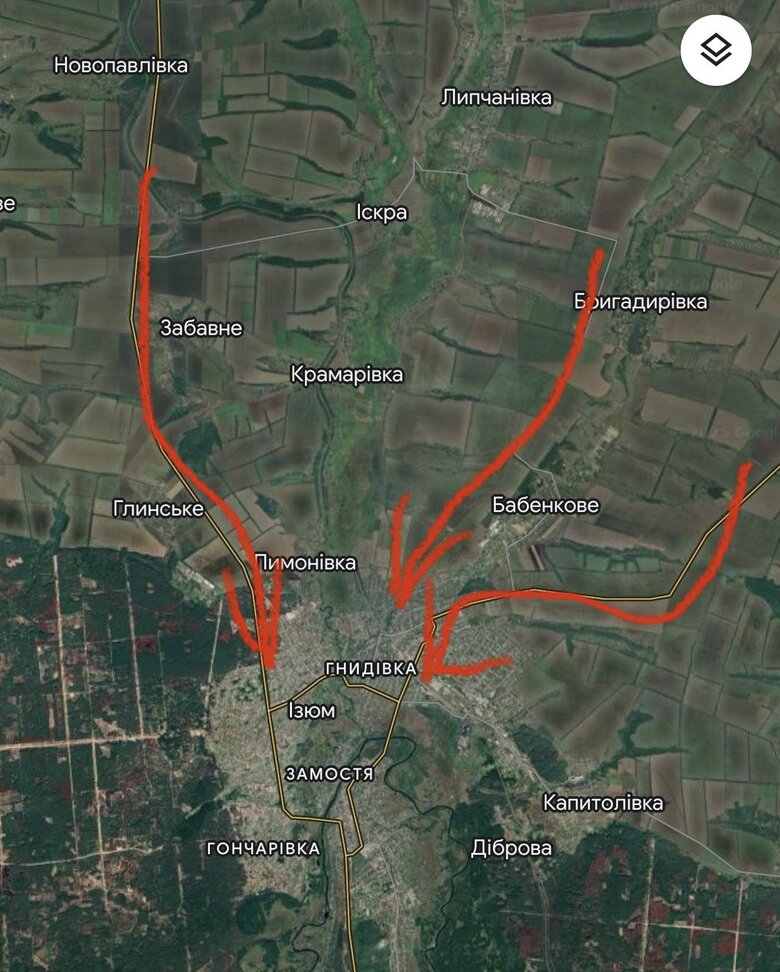

In the first days of the full-scale offensive in 2022, Russian forces planned to enter Izium from the Kharkiv region and advance toward Sloviansk. Additional troops were expected to make their way from the south. This strategy aimed to encircle the Ukrainian army grouping in Luhansk and Donetsk regions. However, the occupiers’ plan failed. Izium, particularly its right bank, became the high ground where Russian army columns were shattered. It is not entirely correct to say 'on the bank.' The enemy was stopped by a very small unit of Ukrainian soldiers from the 81st Airmobile Brigade and a group from the 3rd Special Forces Regiment. It was they who slowed down the Russian advance in this direction and forced the enemy to seek alternative routes to continue their movement. And this time allowed our soldiers to reinforce their forces and prevent the Russians from realizing their plans. This is now part of the historical record of what happened in the first weeks of the full-scale invasion. A year ago, we published a chronological account of the battle for Izium as told by a scout from the same battalion, Roman Sen, call sign Bravo.

The commander supplements it.

"AT 10 AM I HAD COFFEE IN A CAFÉ, AND BY 12 PM THE OWNER HANDED ME THE KEYS AND SAID: 'I'M LEAVING. LIVE HERE, USE EVERYTHING.'"

- How did you end up in Izium in February 2022?

- At that time, I was the commander of the 90th Separate Battalion of the 81st Airmobile Brigade. That direction was completely shielded. It’s in the Kharkiv region. Everyone was expecting an offensive from the Luhansk and Donetsk regions. But the Russians advanced through Kupiansk and Balakliia, pushing towards Izium. At that time, only the Territorial Defense Forces (TDF) were there. One of my companies had been reassigned to the 25th Brigade near Avdiivka. I remained with two companies when I received orders to move to Izium and organize the defense there.

I arrived in Izium with two companies, a reconnaissance platoon, and MANPADS operators. There, I met the commander of a special forces group—call sign Yashka—Roman Kosenko. He was there with a small unit, about six or seven men, as I recall. The local TDF was also there—about a hundred fighters, all from Izium. I began setting up defensive positions, looking for city maps. We blocked the streets, dug in, and laid mines. But Izium was a city full of civilians. It’s difficult to prepare for defense when the area is still populated.

I arrived in early March. Near the bus station, there was a shopping center called Mars. That morning, around ten, I was still buying an Americano at a café, and by noon, the owner handed me the keys and said, "Live here," before leaving Izium. Everything was happening very fast at that time.

- Did you anticipate that the Russians would target Izium and encircle it?

- No! We were assessing possible directions of their advance. Our forces were covering the Kharkiv highway and the road to Kupiansk via Borova. The enemy could have come from either of these two routes. Yashka was conducting reconnaissance. He always maintained contact with a senior commander and provided valuable intelligence on enemy movements deeper into our territory and their approach toward Izium. He informed me that Balakliia had already fallen, Chuhuiv was no longer under our control... So we focused on holding those two roads.

We set up defensive positions in Izium and mined all the bridges—there were three in total. Only one remained intact, a metal pedestrian bridge, because we failed to demolish it. The town itself sits in a lowland, and there is a hill overlooking it, offering a commanding view of the entire area.

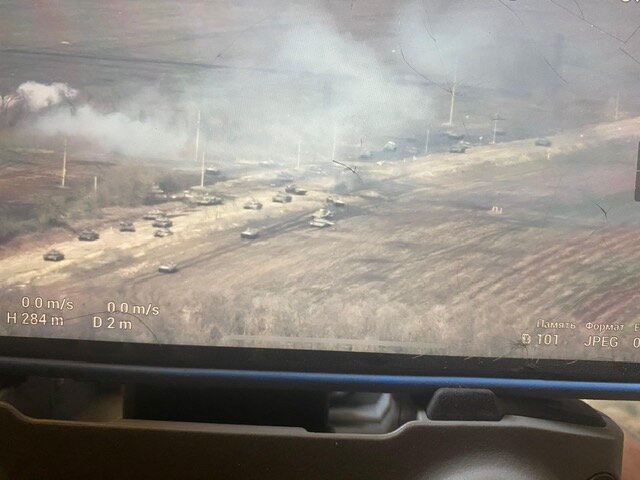

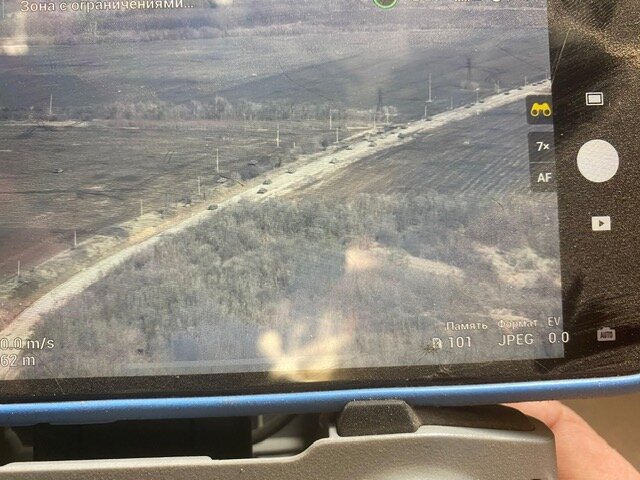

In the photo: Convoys of vehicles heading to Izium from these directions

The first tank appeared from the direction of Borova—it was a reconnaissance-in-force. We destroyed it. A day later, Izium was razed to the ground by airstrikes and missile attacks—Iskanders and Kalibrs.

The city was obliterated in less than a day. I have no idea how many air sorties were carried out from evening until morning, how many missiles were fired, but the sheer number was overwhelming. They hit the Seven Winds restaurant, which was situated on a hill, with missiles—assuming it was the command and observation post (COP) of my battalion or another brigade. But in reality, my anti-aircraft gunners were stationed there, along with a sniper company from the brigade that had arrived in two KrAZ (Kremenchuk Automobile Plant) Spartan armored vehicles. The Russians must have spotted these vehicles and assumed it was a command center, so they launched two missiles at it. After the first missile strike, I was informed over the radio that the company commander had been killed. But later, it turned out he had survived. Then the second missile hit…

The five-story buildings near the bridges remained intact for some time. But eventually, they were also hit by missiles. Everything else—the military enlistment office, the school at the entrance to the city, the police station, the city center, the area near the hospital—was obliterated by aerial bombs dropped from aircraft. We never saw the planes, only heard them: an aircraft would approach, drop its boms, and leave… By morning, Izium looked like a scene from the movie Purgatory. We drove through the city in an armored personnel carrier (APC)—everything was burning, engulfed in flames and rubble... But civilians were still there. Some were being evacuated—the local TDF fighters had shifted from city defense to evacuation efforts. The doctor at the local hospital worked until the very end; we evacuated him ourselves when we withdrew. We also discovered that there were two family-type orphanages in the city, each housing 10-15 children. They reached out to us, and we transported them toward Sloviansk.

- It's all about Kharkiv...

- ...It was already cut off—we were receiving reports on enemy movements. But we still had one last day to evacuate as many people as possible. We tried to organize it.

At the same time, we had to mine the bridges, but we had almost no explosives left. Supplies were being brought in from warehouses—Pions, TM-series mines—while some TDF fighters were making Molotov cocktails. We also had to deploy Stugna ATGMs at elevated positions. In short, the situation was chaotic… And then, at one moment, a Russian military convoy emerged from the direction of Borova. I spotted it on the horizon... It was stationary on the highway. At that point, our artillery was in poor shape. Our D-30 howitzers had been targeted by Tochka-U strikes. I could see the convoy, I could adjust artillery fire on it, but our guns were out of range. Communication was also terrible—it relied on my APC, which was positioned farther away on high ground near Dovhenke. Only from the APC could I establish contact with the commander.

- There were no Starlinks...

-There was none. Cellular service was still available, but everyone was afraid to use it. I had to talk on a mobile phone directly because there were no other options. Using the "Harris" radio took too long. That’s exactly why Yashka was killed—because the internet only worked on the second floor of the TV tower. He had to leave the bomb shelter to get a signal... It was a heavily fortified bomb shelter; I have no idea who it was originally built for. But when we withdrew from Izium on the night of March 13-14, my last COP was inside that ruined bomb shelter. We were still trying to recover the bodies... (More details later on how Yashka’s body and the two anti-aircraft gunners were retrieved six months later.)

- Two of your men were there, right?

- Yes, my anti-aircraft gunners. Anyway, that was the only spot where we could get an internet connection—nowhere else. That’s why Yashka was always up there, gathering information and relaying it himself.

By the time the Russian column was in position, our artillery couldn’t reach them, and when it did fire, accuracy was poor. The enemy started entering the city. Two tanks rolled in—we took them out using NLAWs and RPGs because I had grenade launcher teams. But I realized that we wouldn’t be able to hold that side of the city with just two groups of 60 men, a reconnaissance platoon, and a handful of remaining TDF fighters, most of whom had already "faded away." The plan was to withdraw from the city while inflicting maximum losses on the enemy before they reached the bridges. We couldn’t hold the city indefinitely. So, we crossed the river, demolished the bridges, and took up defensive positions on the far side—cutting off their advance. That’s exactly what happened: they pushed into the city, we hit them hard, but unfortunately, a couple of our grenade launcher teams were captured. I had specifically dressed them in civilian clothing—they moved around in civilian cars while carrying NLAWs, RPGs. But as the enemy pressed forward, we managed to extract our remaining forces and detonate the bridges. The original plan was to lure the convoy deep into the city… They were moving in columns down the streets. I wanted to follow standard tactics—wait for a column to reach the bridge, get six vehicles onto it, then blow it up, sending them into the river. We would handle the rest afterward. But it didn’t go as planned. One of our guys got nervous—just as the first vehicles started crossing, he detonated the explosives too early. The bridge collapsed, and the rest of the convoy began retreating.

Then the Russians started maneuvering around from the other side. We took out a couple more enemy vehicles and blew up the second bridge. That was it. After that, they began systematically pounding us with artillery and airstrikes. We didn’t have time to demolish the Iron Bridge. Why? Those five-story buildings that got hit by missiles... To be honest, I didn’t expect that. There were machine gunners positioned on the fourth and fifth floors, covering the iron pedestrian bridge. And when the Russian National Guard—the first 15 "Jackie Chans"—crossed to our side, they holed up in a small church. My recon guys went in to clear it out. They went there. They asked: "Who are you?" - "Russian national guard". That was all they needed to hear—they knew these weren’t our guys. A firefight broke out… We wiped them out, but I realized the Russians had started pushing across the bridge. We cut them down there—they abandoned their attempt. That same night, missiles struck both of those five-story buildings—one after the other. I lost a group of men in one, and another group in the other… That’s how we held on, while they kept systematically trying to push us out.

- Had you already moved out of Mars when they started getting closer?

- No, I was still on Mars.

- When did you move out?

- We were fighting. The city was on fire. I remember going into a school, stepping into a classroom, and lying down on a desk. Then I heard a plane coming in. I’ll never forget that sound... It was making a bombing run, and it dropped a bomb right on the block where the schoolyard and the five-story buildings were. The blast just threw me off my feet. My deputy called in over the radio: "Are they firing FFARs (free-flight aerial rockets) at you?" I replied: I said, "What FFARs? They're dropping bombs!" He was positioned slightly higher up in the city—he could hear everything, but he didn’t realize what exactly was happening.

Why did we stay at Mars? The Russians burned an armored personnel carrier (APC) that we had camouflaged nearby. They must have figured out that we were there. But the shopping center had a solid basement—a former gym. That’s where we were, along with my recon teams. My 1st company started falling apart because their commander was wounded and had to be evacuated. The soldiers began pulling up stakes from their positions, moving higher into the city. So, I drove to a gas station, caught my "runners," and told them: "Alright, that’s enough—hold the line, gang!" They had assumed their commander was dead. But then, just as an APC rolled by, he was inside, waving and smiling. I really feel for Serhii… He was a real officer, a sharp company commander. Unfortunately, he didn’t make it later. He was taken to the hospital, underwent surgery, got stitched up, and just four days later, he escaped from treatment and came straight back to the war.

I got my soldiers back in position, reestablished communications. That was it—we were back to fighting. My scouts were holding the line. Things seemed to stabilize a bit. Artillery was firing, planes were flying overhead, but overall, we had control of the situation. We could see enemy movements. We had Stugna ATGMs deployed—if a tank rolled out and came into our sights, we took it out immediately.

One day, the brigade commander called me in. I left the city, and we talked. And then a report came through—another breakthrough towards Izium was underway. I thought, The bridges are blown—where could they be advancing? Turns out, they were trying to cross the iron pedestrian bridge, but that was only for infantry—no way to get vehicles across. I jumped into a car and raced back. We were driving at full speed. No communication. As I approached Izium, the signal started coming back. I realized my deputy commander was in charge and that the situation was under control. I rushed towards Seven Winds, started descending, and suddenly—Russian IFV opened fire on the car from across the river, even though it was a civilian vehicle. Near the Marshal gas station, we swerved into an alley on the left and huddled under a fence while the IFV was destroyed a nearby house. The driver looked at me, wide-eyed: "What do we do, commander?!" I told him: "Get in the car and drive back." I sent him the coordinates. Then I was sitting alone under the building. I made it to Marshal. I could hear artillery working, but I was trying to figure out how to reach Mars. I decided not to take the main road but to cut through the cemetery near the memorial and into the lower district. I thought they would not shell the cemetery.

- Naive!

- Yeah… Not very human of them… Then I heard the launch of Grad rockets—the entire cemetery got hit… I thought, Nope, gotta run! I sprinted to Mars, but it was empty. I could hear them on the radio, but I couldn't reach them—signal was too weak. Then I finally broke through: "Where are you?" My deputy responded: "We're at the SSU building." I said: "Send me a rough location—I’ll find my way." And that’s how I ended up wandering through Izium… I didn’t even think about dying.

- And the loss of control?

- I had a smart deputy commander—always by my side. He knew how to lead. Now, Vladyslav Tsyba is the Chief of Staff of the 77th Brigade.

I found everyone in the SSU building. Everyone was alive, everything was fine. We reestablished communication—everything was back under control. I said, "We need to check the tower, see what’s going on there." We hadn’t been there since the missile strike. Seven Winds, the restaurant itself, was still intact. I took one of my deputies, got into my command APC, and we pulled under the shelter of the Marshal gas station. We were standing there—me, my deputy, the driver-gunner, the crew of the combat vehicle. Then a civilian car pulled up, a family inside—they were evacuating from Izium. The man approached me. The gas station was already partially damaged. He asked if he could get some water. I said, "Yeah, of course, take what you need." He opened the trunk, his wife loaded the water, and they grabbed a few more things. Then the guy came back carrying an armful of beer, stuffed it into the trunk—and they drove off... We were still standing under the awning when suddenly—we heard an incoming round. A shell landed right next to a gas cylinder at the station. The tank ignited, flames shot up… My driver shouted, "What do we do?!" I said, "Get in the vehicle!" We sped away from Marshal, heading uphill. But the Russians had eyes on us. I got out, scouted around the TV station, and went down into the basement—not through the main entrance, which was blocked by rubble, but through a side entrance to the right. The basement was empty, just piles of abandoned belongings. I made my way to the main entrance and saw people trapped under the debris—I could see the legs of two bodies pinned under the slabs. Motionless, frozen… That confirmed it—this place had taken direct hits. But the bomb shelter itself held strong. I returned to the SSU building, gathered my command team, and we relocated to the TV station. We stayed there for another three days.

"I WENT INSIDE THE SEVEN WINDS RESTAURANT—EVERYTHING WAS STILL INTACT. TWENTY MINUTES LATER, A ROCKET HIT IT."

- How many men did you have left from the two companies you entered the city with?

- We had about 30-35 killed and wounded in Izium. Each company had roughly 45 soldiers left, plus a reconnaissance platoon. Unfortunately, the anti-aircraft gunners were buried under the rubble. Two more groups remained, but I realized they weren’t needed here—we weren’t going to shoot down any aircraft—so I withdrew them.

- What about the soldiers of the 3rd Regiment? Had that group already withdrawn?

- After Yashka was killed at the TV tower, the rest of the group left the city.

- At that moment, did you realize you were holding back a much larger enemy force that was pushing toward Sloviansk?

- We understood that. The enemy had overwhelming numbers. But I knew the city’s geography well. The river was a natural barrier—they wouldn’t be able to cross it. If they tried to set up pontoon bridges, we would destroy them.

We held our ground. We withdrew to Seven Winds. I moved around, checking positions, getting reports on Russian movements. I walked behind the Seven Winds restaurant. The view from there was incredible—it gave us a great vantage point. That’s where I had a Stugna ATGM set up. A Ural truck arrived with reinforcements—not many, around 20 soldiers. I immediately assigned them to unit commanders, who led them down into Izium to their positions. The driver of the Ural and another soldier had just stepped inside Seven Winds when a rocket struck. The roof collapsed. Unfortunately, they died...

I went inside when everything was still intact. I returned to the shelter. And then I was informed that a missile had struck. I came out—and there was nothing left. About twenty minutes passed between the time I was there and when the restaurant caught fire.

- How long were you on the hill? A week?

- A little longer, up to ten days. There was no panic, no chaos. On the contrary, everyone was focused, and there were no signs of wavering. Everyone understood what we were doing. But unfortunately, the Russians kept advancing. They pushed forward, tried to break through, but failed. And the fighting shifted to the left flank—Tykhotske, Donetske, Komyshuvakha. That’s where they established a pontoon crossing.

They realized they couldn’t achieve anything in Izium, so they moved further along the Siverskyi Donets. The defending forces stationed there were unable to destroy the crossing. The brigade commander called me and said, "Watch, they’re about to strike with Tochka-U." I even saw the plumes, but they missed. And the Russians managed to cross the river with their equipment and advanced from Komyshuvakha toward the Izium checkpoint, approaching from the Sloviansk direction.

- Up the hill where you were, but from the other side....

- Yes, yes. I realized that I was in Izium with two companies, while the enemy was already at the checkpoint. I positioned a unit along the route leading down the hill toward Sloviansk to prevent them from flanking us from the rear. But they didn’t enter Izium; instead, they bypassed it and pushed straight through to Kamianka. I got calls asking, "Are you still alive there?" I replied, "Yeah, I’m alive." — "Do you even know what’s going on?" The war had already moved to the rear. No one was shooting at me, no one was trying to kill me, I didn’t see anyone, no aircraft were flying overhead—it had all shifted deeper. They told me, "The Russians have moved into Kamianka, the 95th Brigade’s other units are fighting there." I asked what I should do: hold my position or try to break through and withdraw? "Hold on for now, we’ll figure something out," was the response I got. That was March 12.

- And what about ammunition resupply? Did you have enough food?

- We had everything we needed. I wasn’t worried about fuel for the APCs since there were refueling stations. Food wasn’t a concern either—there were stores, plus we had our own stockpiles. There were no supply issues at all. Same with ammo—we had been fully loaded in advance. The real problem was communication. I had a stable connection with my men in Izium, I knew what was happening, I understood the situation. Communication was intact. But I had no idea what was going on behind me. I had to call over an open line: "Hello, what’s the situation?" March 12 was my birthday—I turned 30. My deputy came in and somehow found a pack of M&Ms—you know, the small pack. He handed it to me and said, "Here you go, commander, just don’t go anywhere and get yourself killed on your birthday." (Laughs)

- A fitting wish in those circumstances...

- And we held out for another day. We stayed put. Some high-ranking figures from our general staff got in touch with me personally, asking if I could hold my position in case enemy troops attempted a breakthrough. I said, "Of course. No one is storming us yet, no one is killing us. We’re holding our ground, maintaining a perimeter defense" – "Alright, reinforcements are on their way. They’ll break through from Kamianka and relieve you. We’ll lock down the area and push back." That never happened, and I was given the order to withdraw.

I had only one possible route for withdrawal. I found a road on a General Staff map from around 1980—running along the Siverskyi Donets. There was no internet, no way to check Google Maps to see if that road still existed. No Starlinks, nothing. I had to rely purely on luck. I figured that the road from the Izium checkpoint led down to the river. If the enemy had taken the checkpoint, they would have moved down to the river and secured the crossroads there. That meant heading toward Kamianka was not an option...

I gathered the company commanders, the reconnaissance platoon commander, and the brigade sniper teams and gave them their orders: the snipers would advance first, secure the crossroads, and confirm that the area was clear of enemy forces. Once they reported back, the first company—led by its commander, with vehicles and squads—would move out, reach the far side of Kamianka, and check in via radio. Then the second company would follow. I would be the last to leave, along with my communications officer, the deputy battalion commander, and the reconnaissance platoon. Everyone understood the plan and acknowledged their orders.

The snipers moved out—no report, nothing. Still nothing. I finally got on the radio: "Where are you?" The group commander responded, "We’re already past Kamianka." I said, "You idiot, your task was to secure the crossroads so I could be sure that all companies and units had passed through you!" We had to adjust the plan. I assigned the 1st company commander a new task—he led his men out in phases: first, a small group moved forward and secured the position; then he brought out his entire company. After that, another company passed through his secured position, picked up the initial group, and they all withdrew together. Finally, I was the last to leave with the deputy battalion commander, the signalman, and the remaining platoon.

So we withdrew along the Siverskyi Donets. It was early spring—cold, snow on the ground. We were all ready to fight, weapons at the ready, because we had no idea what to expect. We left Izium and made it to Kamianka. There was heavy fighting—just an absolute bloodbath… To be honest, I thought we wouldn’t even make it past the approaches to Kamianka. There’s a small river and a dam leading into Kamianka, and I knew they might be waiting for us there. We crossed that dam, then moved through a farm. That’s how we withdrew Izium.

- And where did you end up?

- Past Kamianka, almost to the turn toward Dovhenke. That’s where we were picked up. The Russians ran into stiff resistance in Kamianka and couldn’t advance any further.

Maybe they could have pushed through, but after crossing the pontoon bridge, they also sent forces toward Komyshuvakha—spreading themselves too thin.

- How long were you given to rest and recover?

- About three days. Then we went to fight in Kamianka. We fought there for around five days, holding the defensive line—positions in basements, some digging in. But the enemy had the high ground. Their tanks would roll out and fire on anything moving along the road. There was no proper evacuation, only through the farm or from the other side. The Russians tried to flank our forces via the dam from the opposite direction—not the one we had bypassed. Unfortunately, my platoon commander was killed there. I had sent him with two ATGM teams to reinforce the position. The guys took out a lot of enemy vehicles, but both the platoon commander and the ATGM crews were lost—they were hit by artillery and tanks. The ATGM team commander, Oleksandr Leunov, was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of Ukraine.

- How long did you fight in Kamianka?

- Four days—not long. The enemy didn’t push further. One day, 20 tanks arrived and took positions on the high ground overlooking the road to Izyum. At that time, we had only one Mavic drone. At the COP near the petrol station—there’s a side street on the right, and down in a basement there was another COP, up on the hill. We sent up the Mavic to get a count. Four tanks moved lower and started shelling the outskirts of Kamianka, randomly hitting houses. We fired back with Stugna ATGMs and took out two of them. The remaining two pulled back, but then another four moved down and kept leveling buildings. This time, we managed to destroy one more. They held that position for a full day. In total, we destroyed five tanks, and after that, they never came down again.

The next day, we sent up the Mavic and spotted a convoy—about 80 vehicles. They were approaching Izium from the left flank. They got lost, started turning around, and began to withdraw. They nearly reached the checkpoint but then took cover in a tree line. A while later, another convoy emerged—I stood there and counted. 300 vehicles! Even Msta self-propelled guns were in that convoy—three SPGs along with their command and staff vehicle. Staff APCs, BMPs, MTLBs… A full army column. Coming from Komyshuvakha, they reached the Izium checkpoint down the road— one convoy stood next to it

I immediately called the senior commander, requesting an Uragan strike on the convoy. They fired somewhere, but they missed. So the convoy kept moving, heading up the hill toward Izium. I kept reporting the number of vehicles and their types. Then another column of tanks arrived. The first one stopped at the crossroads, at the checkpoint. It sat there for a moment and then started advancing toward us...About 40 tanks plus IFVs were coming straight at us. And on top of that, the ones we had been engaging earlier were still out there. A massive force! And they weren’t stopping—they maneuvered around the stationary tanks and began descending toward Kamianka. At that moment, I realized—this is it, we’re done. They were actually coming down. The first tank hit a mine and exploded, then the second… In total, we took out six with NLAWs, but they still managed to break through into Kamianka. IFVs carrying infantry stormed into the streets. We engaged them in combat, exchanging fire. Meanwhile, enemy tanks bypassed my COP from behind and continued toward Sloviansk. I reported this, and the response came back: "Do something." We kept holding, but we knew—this was probably the end. My deputy turned to me and said, "We're all going to die here." I told him, "We’ll see!" We fought as hard as we could, but then the order came: "Withdraw. Try to get out." My deputy and I crawled across the field—a full kilometer on our bellies. There was no other way out. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have made it. But we did. And so did my companies. They overwhelmed us—not with tactics, but with sheer numbers —infantry, armor.

They broke through Kamianka, and their next military objective was Dovhenke—the turn toward the village, the village itself, and what I call the Sherwood Forest. This was the junction of two regions—Donetsk and Kharkiv. I held the position at Sherwood Forest and everything surrounding it. By that time, I had already been appointed battalion commander in the 81st Brigade, while the 95th Brigade was responsible for Dovhenke and the area beyond.

At that moment, the 81st Brigade had only one of my battalions in place—the second was fighting in Rubizhne, while the 5th BTG (Battalion tactical group) was engaged in the south. Our battalion's area of responsibility stretched 40 kilometers. I also had to allocate forces to help contain the advance of either the 19th or 20th Russian Army pushing from Borova. They were moving toward Pisky-Radkivski, Yatskivka, and Krymky. I had just one company fighting them there—to give you an idea of the scale. The first place we managed to hold them was Oleksandrivka. Before that, my guys had just been getting hit, barely holding on. We managed to gain a foothold only in Oleksandrivka—set up a proper defense and start hitting them back effectively. I also had two more companies stationed in Sherwood Forest. So, in one direction I was in Oleksandrivka, where the situation was toughest at first, while my deputy took command in the other. We split up to maintain proper control. The Russians never entered Oleksandrivka. Instead, they moved forward—toward the positions of the 79th Brigade, in settlements like Korovyachyi Yar and Shandryholove. They bypassed us completely and, advancing from Yarova, started pushing into Sviatohirsk. That meant they had flanked us, overran the 79th Brigade, forcing it to withdraw to Lyman, and reached Sviatohirsk. I was ordered to withdraw my forces from Oleksandrivka, move through Sosnove, and hold Sviatohirsk. But… by then, all the bridges in Bohorodichne had already been blown up. Only one bridge remained—near the Sviatohirsk Lavra—and that was it. Just one of my platoons was still there.

The war started in Bohorodichne and in Sherwood Forest. We held our positions there until the Kharkiv offensive.

"I CALLED THE FOREST NEAR SVIATOHIRSK SHERWOOD'S FOREST BECAUSE THE FIGHTERS WERE CONSTANTLY WANDERING IN IT, AS IF IT WERE AN ENCHANTED PLACE"

-How did you manage to hold back the Russians near Sloviansk? You had fewer troops, less equipment, no air superiority—everything was against you. Yet, you stopped that overwhelming force of armor and manpower...

- We held out thanks to the resilience of our soldiers and officers. It was incredibly tough. But at that time, every single one of my officers and company commanders was fighting as a soldier on the front line. All of them! Of course, company commanders should be protected. But back then, we didn’t have FPV drones, no payload drops. Artillery was working, but that was it. And when a soldier sees his company commander sitting in the trench beside him, digging alongside him, checking on other platoons—he reacts to that. He gains confidence, holds his ground. Under such conditions, soldiers stand firm, they don’t run. But the TDF units that were sent to us? They fled. Badly. Everyone ran. Meanwhile, my soldiers fought. They were given a target, they fired.

- And when a tank is coming straight at you, firing direct shots—who wouldn’t run?

- NLAW—and forward!

- A plane is flying overhead...

- I have one story for you. This happened at the regional border, near the stele. There was a road, and in the roadside ditch, a position where two of our guys were dug in. A Russian aircraft dropped a bomb on the opposite side of the road. And the guys? They survived. Just got covered in gravel—that’s it. To keep morale up, I kept moving through Sherwood Forest, checking our positions. Even when I was leaving my post as battalion commander for a promotion to the 95th Brigade, I still made my rounds as usual. That’s when I got caught in an artillery strike. One of our soldiers was killed... Everyone was burned out, but no one panicked. No one feared death. They fought. They stood their ground. But, the losses were devastating. From February to June, by the time I left, my battalion alone had already lost 138 men. Not the brigade—the battalion. More than 700 wounded. 21 missing in action. 15 taken prisoner. By now, almost all of them have been exchanged. But… the losses were enormous. As a commander, I took it all to heart.

- How was your unit replenished back then? Who came to you?

- I had motivated personnel. Everyone came voluntarily—they were determined to win. Of course, there were some unusual cases. One time, a company commander positioned his men and then sent me a photo of a grown man who had set up his own "defensive position" in Sherwood Forest: a tree trunk with a pile of branches stacked against it, like a makeshift wall… And he was just sitting behind it. I couldn’t help but laugh at his idea of a shelter. And this was a full-grown, capable man… I had to explain to him that he needed to dig into the ground.

- Were you the one who called it Sherwood Forest?

- Yes. Because people were constantly getting lost in it. Maps didn’t work properly. You’d open the General Staff map—it showed a stall roadway. You’d follow it, thinking everything was correct, but when you checked Garmin, you’d already drifted 150 meters to the left. You weren’t where you were supposed to be anymore. So you’d turn back—because it wasn’t the stall roadway. My men kept losing their bearings there, and the Russians? Even worse… Once, a Russian soldier carrying ammunition and supplies for his unit got completely lost and walked straight into our 3rd company’s position. "Who are you?" "3rd Platoon, 3rd Company, Russian Federation." "Come on in!" He walked in—and we grabbed him up...

- The forest was dense...

- Pine and oak trees. One time, a group was evacuating a wounded soldier. Another group—Muscovites—was approaching them head-on. They passed right by each other. Like there was a wall between them—they simply couldn’t see one another through the trees. My soldier only spotted the last one in their formation—and that’s when the firefight started. The Russians had highly skilled intelligence operatives there—RF DIU military intelligence. We also fought with them - the 13th Special Forces Brigade was fighting against us, and we killed a lot of them. When we killed one captain, we found a watch with data on it... We saw that he had been walking around our rear, around our positions, and had revealed our entire front line. He had marked points: a generator there, an observation post... He was experienced, he had been in Syria, fought near Kyiv, in Kharkiv.

We tried to position our troops along the front line so that they could maintain visual contact with one another, tightening our defenses. But somehow, the enemy kept infiltrating. One of my company commanders, along with a group of sappers, walked into an ambush while inspecting positions. Unfortunately, he was killed… But the head of the engineering service, Oleksandr Sipov, call sign Anubis, fought back alone, killing two Russians, grabbing the wounded company commander, a radio, and wrapping himself up—he had five bullet wounds in both legs. And still, he dragged him back to rear. We rushed in with an APC, picked them up, and evacuated them. That’s when we realized the enemy was already in our rear—so we started combing through the forest. Roma Sen and his group led the effort. Later, as our numbers dwindled, scouts were reassigned as infantry and sent to hold positions. That was when Roma was seriously wounded. We lost so many motivated, highly trained scouts.And not just them—there were men with real combat experience, those who had fought back in 2014–2015 and returned in 2022…

I remember those days, and there are no words. It was very hard.

I had a COP in the center of Bohorodichne. We set up a backup position—underground—because we knew we wouldn’t be able to hold out in houses for long. And then, just as we were relocating, a Ka-52 helicopter took off, flew past the Lavra——and hit our COP. The place where we had been sitting was burned to the ground. Oleksii Znaiko, call sign Mongol, the driver of the 1st reconnaissance unit, was killed. My sergeant major, Andrii Repniak, was wounded…

To be honest, I’m more afraid now than I was back then. Because now I see how the Russians are advancing, how they’ve adapted, how they’ve improved. They’ve adopted our own technologies. They’re even using fiber-optic-guided FPVs, advanced electronic warfare (EW) systems… They are stronger now than they were back then. And we’ve weakened. Not in terms of technology—but in terms of people.

- What's the scariest thing?

- For me personally, it's aviation, the aeroplane. Before the full-scale war, I thought 152mm artillery was terrifying. Not Grad, not tanks, but 152s—when they hit, they hit hard. But when the full-scale invasion began… Iskanders, Kalibrs—they fly around like they own the place. Still, it's not as terrifying… A missile might be more powerful than a bomb dropped from a plane. But a fighter jet or bomber—it gets inside your head. When it's diving toward you, you just think: That's it. I'm already dead. Nothing has even exploded yet, and you already feel like you're gone.

- Have you ever traveled abroad?

- Never. I was planning to go to Egypt in 2022. Made passports for my kids, for my wife (laughs)—and then all this happened...Now I plan to go in 2025.

- So, technically, your first trip abroad was to Russia...

- Yes. That was my first foreign trip.

- And?

- Nothing special, to be honest. (laughs).

- There were some predictions in 2014: we will finish it all now! Or did you realise then that it would take a long time?

- I've been in the ATO since 2014, starting as a platoon commander of the 90th battalion, then I was a company commander...

- I have passed all the stages.

- I was in the hottest spots of the ATO—Donetsk Airport, the Svitlodarsk Bulge, Izvaryne during the breakthrough, and the Avdiivka industrial zone. In other words, I was everywhere. Even back then, I understood this war wouldn’t end quickly, that it would drag on for a long time. I never had the feeling that it was just going to end somehow.

Before the full-scale invasion, we were scouting potential defensive positions along the Kharkiv region’s borders. The chief of staff assigned me the task, and as a battalion commander, I assessed the areas—just in case something happened there…And then it happened.

Violetta Kirtoka, Censor.NET