"Military surgery is like plane going down. You don’t have to land it in one piece. But crew and passengers must survive," - military surgeon Andrii Drozdov

37-year-old Andrii Drozdov is the kind of person who acts first and only then (maybe) speaks. And since the surgeon of the 66th Military Mobile Hospital is swamped with work, it was Censor.NET who had to (or rather, was lucky to) pepper him with questions.

Despite the many months of intense work on the frontlines that Andrii Drozdov and his colleagues have behind them, he’s in no rush to call himself a soldier:

- I serve as a military surgeon in a mobile field hospital, but I don’t see myself as a soldier. I don’t see myself as an officer either, even though I do hold an officer’s rank. Why not? Because, to me, it’s still medicine...

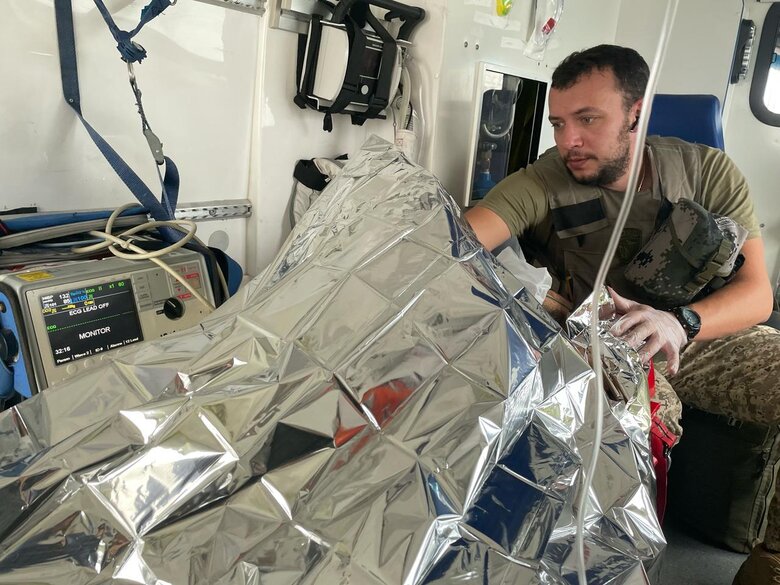

We asked him about the most recent surgery he performed in Pokrovsk (it was Drozdov himself who carried it out). About the months spent working on the frontlines without a single day off. About what it's like to operate under the sounds of explosions — and what helps doctors keep their "sanity". When, with a massive influx of wounded, the senior medic at the stabilization point has to decide who goes to the operating table first...

And we started from the very beginning — with his call sign.

- Andrii, is it true that you don’t have a call sign?

- That’s true. People just call me by my first name — or by my patronymic.

- And if you did have one, would it be Drozd?

- Possibly. My cousin, unfortunately, he was killed — his call sign was Drozd.

- Where and under what circumstances was your cousin killed?

- Near Toretsk. A UAV strike.

- One of your fellow surgeons told me about his reaction on February 24th, 2022: "I woke up to the sound of bombing. I just lay there thinking: well, I’ll be doing wartime surgeries now…"

Did you have a similarly calm, melancholic reaction to the start of the war?

- No. On 24 February, I woke up to a call from my wife, that day, she was at her parents’ place with our 7-year-old son. She woke me up and said the war had started. At that moment, I wasn’t thinking about the military, or the army, or becoming a military surgeon. All I could think about was my family. I had to get to the left bank, pick up my wife, our son, and her parents, and take them somewhere. It almost didn’t work out that first day because of massive traffic jams. I brought them to the Kyiv emergency hospital where I was working at the time.

A scene from the pre-war working life of Andrii Drozdov

We stayed there until the evening, waiting for the traffic jams to ease, and eventually, I managed to take them to a village. I thought my wife, our son, and her parents would stay there. But she said: "No — I’m going with you." So we spent the first month, while Kyiv was under siege, living at work. Just working.

- A lot of people thought Kyiv would be bombed and that the city would be dangerous, but that it might be safer outside of it.

Unfortunately, we all know how that turned out.

-Our village happened to be in a relatively safe area. Thank God, everything turned out fine there. But my wife stayed with me anyway.

I set up a small medical point for the Territorial Defense in Obolon and started going to the military enlistment office. I even filled out the mobilisation form. But then a captain came out and told me, "We don’t need officers." After that, I stopped going to the military enlistment office.

So it happened that I remained a civilian all the way until 2023, even though I did go to the front as a volunteer. I was in Bakhmut in October 2022, when Russian troops were already entering the outskirts. I also worked as a volunteer with different mobile hospitals. And in November 2023, I finally got my draft notice and officially joined the army.

- Where were you assigned?

- That’s where it got interesting. I wanted to join the 47th Brigade, where my friend serves. But at the military enlistment office, they told me there’s a directive requiring everyone to go through retraining. I ran around, argued, even went to the main TCR (Territorial Center of Recruitment and Social Support), but it didn’t matter — I still had to do the retraining.

- And after retraining, you still couldn’t join the 47th?

- I could. I was supposed to. I even had the assignment request letter. But the thing is — they pulled me out earlier. I won’t say who, but someone found out I was about to be mobilised — and they brought me to the hospital. They knew what kind of surgeon I was. They knew how I operate — and they took me.

- Some solid headhunting. Did the retraining give you anything new?

- Not much. The retraining mostly covered general tactics — stuff we’d already gone through at university during military training. Overall, those courses are more useful for people going into administrative roles — chief medics and the like. For practicing doctors, there wasn’t much that was new.

- Then you were transferred to the mobile hospital in Pokrovsk?

- Yes. I was the last person to perform surgery there. We had several locations. One used to be in Pokrovsk — not anymore. There are a few others nearby, but I’m not sure if I can say exactly where...

- The reader will forgive us if we skip that. Do you remember your last operation in Pokrovsk?

- I remember all the more interesting ones. This one was a popliteal segment injury — the popliteal vein was completely severed, and the artery was bruised. I'm not a vascular surgeon, but this year I’ve had to operate on pretty much everything...

- So you're performing the surgery, and meanwhile…?

- Explosions. They were hitting the city with GABs (guided aerial bombs). Even FPV drones were flying in. A day before we pulled out of Pokrovsk, an FPV drone flew right into the courtyard. One of our colleagues was wounded.

- How does a surgical team of six or seven people even work under those conditions? I mean, sure, you’re focused on your job, but it must be hard to ignore what’s going on around you. How did people react to the explosions?

- You get used to it. When things got critical, we moved the operating room to the basement. It was a decent one — we could work there. But still, you could hear everything. You could feel the shockwaves.

- That’s what I mean. Did people flinch?

- Honestly? They don’t flinch anymore. You just get used to it. We had rotations — 20, 24 days. For example, I’d go to Pokrovsk, then come back, then go again. The first few days after you arrive — yes, it gets to you. But after that, you adjust.

- How did that last operation end?

- Successfully. You see, military surgery is like a plane going down. Take an injury to a major vein, for example. We don’t attempt a reconstructive procedure — we simply ligate it, because the limb still has a high chance of survival. There’s no point in doing more. But when it’s a major artery, then yes — we do our best to repair it, to restore blood flow, to do everything we can. In this case, it was just the vein, so we ligated it. The patient’s doing fine.

- So, the task of the medics in the evacuation vehicle is to deliver the wounded alive, stabilizing them somehow, to the stabilization point, an intermediate point. And the surgeons' task at this intermediate stabilization point is to prepare the male or female soldier for safe transportation to the next level of care. Am I understanding this correctly?

- Partly, yes. But at Pokrovsk, we tried to do as much as we could in the shortest possible time. Sometimes I was even told not to — but I still tried. For example, I’d insert a shunt for arterial injuries, do everything I could so that doctors at the next stages would only have the minimum left to do. But you’re right: the main task of a frontline surgical unit is to save lives. And the injuries we received — they were really severe.

- When did you first get experience working close to the front line?

- Back when I was still a volunteer. And in the Armed Forces, it was at Pokrovsk. Back then, the front line was still relatively far away. But my very first day there, I had five difficult surgeries. Heavy bleeding. Five operations in one day. That’s how I spent my first six months in Pokrovsk.

- Have you formulated the key rules for yourself? What can be done, and what absolutely can't?

- Absolutely. It changes your whole perspective on providing care, both as a doctor and as a surgeon. Military surgery is a completely different world from civilian surgery. I learned a lot of new things. Luckily, before the war I worked in an emergency hospital. Although even there, you rarely see the kinds of injuries we deal with here. At the same time...

- Is the urgency a key factor?

- That’s what I’m saying. It’s like a plane going down — and you don’t have to land it in one piece. But the crew and passengers must survive. That’s how we have to work.

- You also have to prioritize when time is short. What comes first, what comes next…

- Yes, and triage becomes incredibly important when there’s a mass influx. No matter how harsh that may sound. When I was the lead at a stabilization point, I had to assess the condition of every wounded soldier brought in. For example, someone with moderate injuries who can survive and wait a couple of hours — that’s one case. But then you have someone who arrives sitting up, looks okay at first, but you realize he’s in critical condition, and they may only have minutes, tens of minutes left. In cases like that, I had to take them in first. Others had to wait for the operating table.

- Did you often have to make those kinds of decisions?

- Not during the first six months. But later, I was in charge at stabilization points in Pokrovsk and Kurakhove — and yes, I had to. Same as now.

- Is that usually a job of the head of the medical team?

- Yes, and usually it’s the surgeon. I personally think an anesthesiologist could do it too — but for some reason, that’s not how it’s done.

- You come across as a very confident person, but making those calls — that’s a heavy kind of responsibility. Do you feel the pressure? Like — what if I choose wrong?

- Honestly, I never thought about it in the moment. Maybe later, when the rotation ended, or I was somewhere quieter, maybe on leave, yes, I would reflect on it. But during the work, my focus was always on the consequences of the surgery. From a medical standpoint, I’d assess every case afterward. And in critical situations, I often found myself thinking after each operation: Did I do the right thing?

- When it comes to deciding who to take first, have there been cases where wounded soldiers said: "Why not me?"

- I serve at one of the best hospitals in Ukraine. The staff — all my colleagues — are so dedicated, it’s hard to put into words. When we have a mass casualty situation, no one ever takes a break. Everyone jumps in. Even if someone is waiting for surgery, there’s always someone by their side — providing assistance, pain relief, whatever’s needed. Additionally, at every stabilization point we work from, we always try to set up two operating tables, so we can operate on two patients in parallel. It’s not always possible — we’re short on personnel. It’s getting harder and harder to find enough medics.

- So no one ever complained?

- No one ever really complains. There’s always someone with them. Maybe the bare minimum — but an anaesthetist will come over, administer pain relief. Another surgeon might be examining minor limb injuries in the meantime.

- Andrii, have you had any surgeries that left a lasting scar on your soul? The kind that still show up in your dreams?

- Yes. It was a very severe lumbar injury — a penetrating wound to the abdominal cavity, with damage to the lumbar spinal cord and a comminuted pelvic fracture. He was an extremely complex case. He survived, but that area is notoriously difficult to manage — controlling bleeding there is extremely challenging. After about an hour into the surgery, I started having doubts... I didn’t give up, but it was incredibly hard... He required a massive transfusion. But we were able to stop the bleeding, and he was stabilized and transferred to the next level of care. I bring up this case because his chances of survival were very slim. Despite the extensive blood loss, we handed him over stable.

- Were you able to find out what happened to him later?

- We have very poor feedback. In the beginning, I tried to set something up. It didn’t work. The only case where I managed to follow up was my first heart surgery — I pushed hard enough to find out what happened to that patient. But in general, it’s very difficult.

- Do former patients ever try to contact the surgeons who operated on them?

- No. Not once.

- That actually surprises me. If someone saved my life, I’d want to thank them.

- Actually, I don’t really think about it.

- One of your colleagues said this about the war: "A surgeon's work doesn't depend on the direction, because the war is nearly the same everywhere. There are gunshot wounds, shrapnel wounds. Surgery is the same." Do you agree? Or is the Pokrovsk direction somehow different?

- I can't really compare — maybe only with Bakhmut in October 2022. But since February 2024, around the time of Avdiivka, I can’t recall ever dealing with this kind of workload. We had people going without sleep for two days straight.

- How many wounded did you operate on per day, on average?

- I don’t remember the exact numbers, but on average, we received 100–150 wounded per day. Sometimes it reached 200. It’s impossible to put it into words.

- What was your longest shift?

- Hard to say. I basically work without days off. If someone is covering for me and there’s a mass influx, I don’t rest. I go back into the shock room or the operating theatre.

- No days off? How do you stay functional in those conditions?

- Things are a lot easier now. Back then, coffee, energy drinks. Nothing special. We just had to keep working.

- Have you lost patients on the table?

- Yes. Two cases this year. Extremely severe injuries. Unfortunately…

- How does the team handle that? What do you do with yourself — because the next patient is already waiting?

- I’ll be honest: professional medics become cynics — up to a point. But moments like that still hit hard — for me and for the whole team. Of course you feel for the wounded. And in my case, it also made me start questioning myself as a doctor — could I have done more? Afterwards, I’d think about it for a long time. I’d talk to my colleagues — ask if there was anything else I could’ve done. And of course, they’d say no — you did everything possible. But the doubt still creeps in. That said, it fades quickly — because the flow of patients doesn’t stop. You have to stay focused. Always.

- I’ve spoken a lot with doctors working at stabilization points and tried to imagine myself in their shoes. Three years of "long shift – short rest, long shift – short rest" mode, month after month. And honestly, I don’t think I could endure it. How do you manage?

- Just a small note. I have great respect for the medics at stabilization points — I’m on good terms with many of them. But brigade doctors usually get days off. Military surgeons don’t. I can’t speak for everyone, but here’s how it is at our hospital: I haven’t had a single day off in a year. Sure, if I was on rotation at a safer location, I could go to the store for coffee — but I was always on call. I haven’t had a proper day off.

- Not even one day off all this time? How did you stay sane? Everyone needs to reset at some point.

- First of all, we’ve got a solid team. We always try to set up some kind of normal routine, wherever we’re posted. Of course, sometimes we can step outside and take a walk (if it's a safe location). In Pokrovsk, that wasn’t an option. In the final days before we pulled out, we stayed indoors. I ordered the team to stay inside. Because in September, when I was still in Pokrovsk, going outside was already strongly discouraged, but I still felt the need to clear my head. I went for a short walk around the hospital grounds, and a piece of shrapnel landed right near me. You get the picture? In safer places, we might step outside, take a walk. Physical games also help us unwind. We try to do some sports when we can. But I haven’t had a single proper day off this past year.

- And how many vacations did you get?

- Two per year, about two weeks each. Give or take — usually one travel day included.

- But without days off, you’re not getting proper sleep. And the psychological pressure must be intense.

- It often is. That’s why, when young surgeons come to our stabilization point for a rotation — let’s say from a central hospital — I always tell them: my policy is that everyone should rest as much as possible.

- And then you tell them there’ll be no days off. What’s their reaction?

- They don’t have a choice. I joke that they’re coming from the mainland — from Lviv, from Chernivtsi. And they’re only here for three months.

Our personnel have been working like this full-time. But most of them understand — they come mentally prepared. I tell them again: "Rest as much as you can." They laugh and ask: "Why?" And I say: "Because if you get a quiet moment during the day — you need to take it. The next night might be a full-blown nightmare, and we’ll be up for 24 hours straight."

- How far from the zero line did you work last year?

- When we left Pokrovsk, we were about 4–5 kilometers from the zero line. Now, the stabilization point where I work most of the time — where I’ve set up an operating room that I’m really proud of — is roughly 15 kilometers from the front line.

- Do you often have to relocate so the enemy doesn’t zero in on you?

- Fortunately or unfortunately, no. Setting up a field surgical unit (FSU) is not an easy task. When we establish an operating room, we follow all protocols—it's a fully equipped operating room with proper equipment, antiseptic control, and sterile instruments. It’s not something you can throw together quickly. Of course, there’s planning for where the next point might be, but that’s up to command. At the site where I currently work most of the time, I set up the operating room back in December. It’s still operational — we’re even doing renovations there: walls, flooring, everything.

- Listening to you, it’s clear you’re tough — a real die-hard. Have you ever seen anyone who couldn’t handle this kind of schedule?

- I haven’t. But like I said, I’ve been lucky at the 66th Military Mobile Hospital—with the colleagues I work with and those who rotate in. I’ve never heard any colleague say that I’m tired, I need a break, and that was it.

- We’re speaking now in Kyiv, at the end of your leave. You’ve come home, you’ve got two weeks with your family. What do they do for you — and what do you do for them?

- First of all, we always pick our son up from school. He says he’s not going to school while I’m home. My wife tries to take time off too — so far, her employer’s been understanding and has given her leave. That’s all. Nothing special. We just do everything together.

- And when you're at the front?

- My wife loves sending me postcards. I honestly don’t even know where to hide them anymore (laughs). Sometimes I joke that enough is enough!

- What’s on those postcards?

- All sorts of nice things, like we miss you and stuff like that. My wife or son usually add something extra. My son likes sending me keychains of his favorite cartoon characters.

- One of my interviewees, a company commander, sent his wife a photo: a heart made of grenades.

- We don't do things like that. We rarely handle weapons directly. Mostly it's just phone calls and messaging apps.

- Right now, we’re all witnessing the current U.S. President Trump and his team conducting peace talks with both sides in this war. What’s your take on this process? Do you believe in reconciliation?

- No, I don't. Even when it became clear he’d become U.S. president, I didn't believe there’d be reconciliation.

- Why don't you believe it?

- Because of our "neighbor," who we’re so "fortunate" to have. It's a treacherous enemy. In my opinion, they don't see any benefit in stopping the shelling right now.

- Because the initiative is on their side?

- Possibly. A clear example: even after their press conference, Kyiv and Sumy were shelled right away.

Honestly, it’s a philosophical issue. I believe history hasn’t taught Ukrainians anything. They’ve been our enemies for the past 300–400 years.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the yoke fell from our shoulders — but many Ukrainians still saw them as a "brotherly nation." That was a big mistake.

- You’re from Kyiv. When you come home on leave from the front, what are your impressions of the city?

- During my first leave, I was honestly shocked that people seemed to have forgotten about the war. But now, I just don’t pay attention to it — for one simple reason. I don’t think I have the right to make any judgments. I’m not at zero line, not in the trenches — so I don’t feel I have the right to condemn or justify anyone.

Yevhen Kuzmenko, Censor.NET

Photo: archive of Andrii Drozdov