Victory depends on how many Ukrainians take up arms – UAV operator Bond

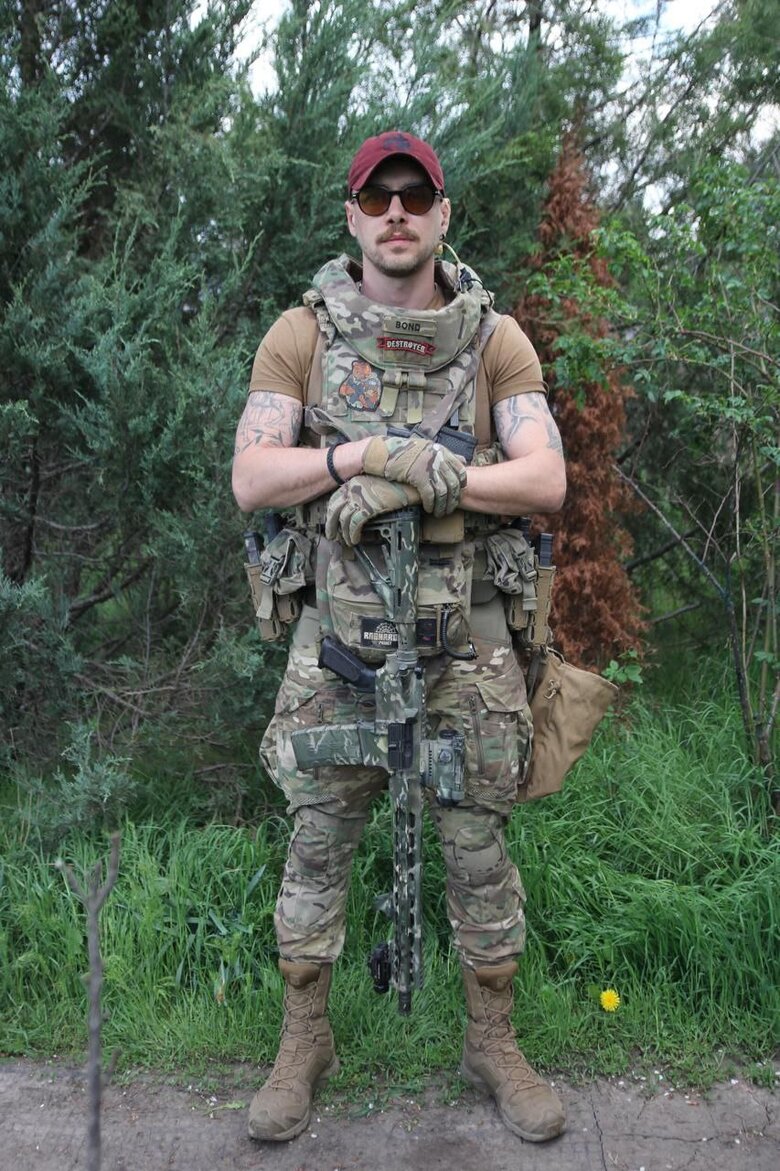

Bond, commander of the "Kotyky" (Ukrainian for "kittens" - ed. note) UAV platoon of the 130th Territorial Defense Forces (TDF) Battalion, is one of the fighters who returned from abroad in 2022 specifically to defend Ukraine. With prior experience as an infantryman and reconnaissance operative, he now takes pride in his unit and its accomplishments.

Bond, commander of the "Kotyky" UAV platoon of the 130th Territorial Defense Battalion, is one of the fighters who returned from abroad in 2022 specifically to defend Ukraine. With prior experience as an infantryman and reconnaissance operative, he now takes pride in his unit and its accomplishments.

During the tense negotiations between Ukraine and the United States following the start of Donald Trump’s presidency, the Kotyky recorded a message addressed to Volodymyr Zelenskyy, pledging to keep fighting even if the United States withdrew its government support. What drove them to do it, what plans Bond has for life after the war, and how he views the current situation on the front line and in the rear – all in his conversation with Censor.NET.

OUR MONTHLY NUMBERS NOW – 127 OCCUPIERS ELIMINATED BY UAV UNITS ALONE

- The choice you made to return to Ukraine from the EU after the full-scale invasion began – was it a difficult one for you and your family?

- In 2022, I was living in Poland, and at the onset of the full-scale invasion, I happened to be in Germany. I called my wife and told her I would be returning to Ukraine. She asked me to wait for the first three days – negotiations were scheduled, and no one knew how it would end. Since I was already far away, I agreed. As you can guess, nothing changed, so I set off for Ukraine.

- What were your thoughts at the time?

- It was quite simple: I understood that no one but Ukrainians would help Ukraine. Victory depends on how many Ukrainians take up arms to defend their country, regardless of which state they currently live in.

I started looking for a unit while still on my way, and focused specifically on combat units already engaged in real operations. That’s how I ended up in the 130th TDF Battalion – as a regular soldier in a rifle company.

- So it all started for you with the infantry.

- The battalion began fighting in the Kyiv region. As soon as it was liberated, we were redeployed to the village of Dementiivka in the Kharkiv region. That’s where I did "the most infantry-type work." It was honestly the best combat experience I’ve had. The Russians tried to capture the village for a long time, and we, a single platoon, held part of it for a month and a half.

From there, we continued advancing through the region. After the Kharkiv offensive, we were redeployed to Bilohorivka – the last Ukrainian-held enclave in the Luhansk region, which remains under our control to this day. Then came a long and memorable chapter in Donetsk region: we saw action in Bakhmut, Ivankivske, Chasiv Yar, took part in the assaults on Makiivka. After that, we were once again sent to the Kharkiv region – to the Kupiansk forest. And then, back to the Donetsk region, where we broke out of three cauldrons. At the moment, we’re operating in a different direction.

- At what point did you end up in the UAV?

- It happened while we were in the Luhansk region. Our platoon was reorganized into a separate reconnaissance unit. We started integrating UAVs into our work because for any assault-related missions or movements toward enemy positions, having drone support was simply more reliable.

At some point, we met an excellent group of guys from the Kharkiv region who specialized in drone-dropped munitions, and we were blown away by their effectiveness. Still being a recon platoon at the time, we began applying those skills ourselves. After seeing how well it worked, we realized this was exactly the direction we needed to pursue. First, it protects our personnel. Second, it helps our infantry avoid direct face-to-face encounters with the enemy. And finally, eliminating targets with drones is much more efficient than with artillery because the operator can carry out near-perfect drops directly onto enemy positions, unlike artillery shells. As FPV drones began to evolve in Ukraine, we started using them through trial and error.

Back then, it was all early-stage experience – we went through crashes where drones would go down 500 meters out, a kilometer out, even 1.5 kilometers… But it was valuable practice because we were actively looking for ways to solve the problems. Today, we’ve reached a level where, on the Kurakhove direction, our monthly statistics (achieved solely by our unmanned systems) include 127 occupiers killed, 95 wounded, tanks and Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs) destroyed, assaults repelled, and shelters eliminated. I think that’s an excellent result. We actually welcome challenges, because they drive progress.

- How do you calculate these figures, like the number of killed in action (KIAs)? UAV operators often say they’re not 100% sure about the outcome, saying things like, they dropped a munition on a house full of occupiers, but don’t know how many were actually killed.

- It’s pretty straightforward: we work off our own footage. We go frame by frame to see exactly what happened and to whom. If everything is covered in blood, or a piece of metal hits someone in the leg – there’s no question they’re wounded. The statistics I mentioned are based on filmed and verified cases.

ON A SINGLE BATTERY CHARGE, I MANAGED TO DROP FOUR MUNITIONS. OUT OF EIGHT ENEMY INFANTRYMEN, FIVE WERE TAKEN OUT ON THE SPOT.

- How effective are munition drops from Mavics? Some remain skeptical, as drones are often lost during munition drops.

- I’m talking about Mavics too. Unfortunately, war is a space where, over the past three years, technology has only continued to evolve, so the issue of drone losses will always be there. But losing a Mavic isn’t nearly as critical as losing personnel.

Our battalion’s command takes a slightly different view. They see the results of Mavic drops and explicitly say it’s an ideal weapon for locating and eliminating the enemy. With Mavic-dropped munitions, we’ve managed to stop enemy infantry assault groups at distances of up to three kilometers. FPV drones, on the other hand, are more suited for countering large groups or enemy vehicles.

- I suppose you were lucky with your command. That’s the impression not only from your unit’s social media page, which is regularly updated, but also from the fact that you have the time and motivation to analyze your own footage.

- A unit creates good working conditions for itself — but yes, we’ve really been fortunate with our command. At this stage, our leadership is young and forward-thinking. They don’t operate by Soviet-era manuals — the focus is entirely on the battalion’s effectiveness. So overall, we genuinely enjoy our work, especially when the results speak for themselves.

- What drones have you worked with, and which ones do you prefer?

- We are not getting away from Mavics. As for FPVs, more than once, we were literally saved by drones supplied by Sternenko. And of course, we can’t forget the excellent heavy bombers. I won’t name the manufacturers — that’s more about our team’s internal story than the drones themselves.

- You mentioned Sternenko. Do you get your drone supplies mainly from volunteers or through the Armed Forces?

- When it comes to FPV drone components, we cover those from our own pooled resources. As for Mavics or Autels, we can’t manage without volunteer support. I wouldn’t say everything comes from volunteers, but their contribution makes up a significant share.

- Do you remember your first combat engagement and what you felt at the time?

- Honestly, I was enjoying it. There were seven of us holding the position. We held a fairly long defensive line. I had multiple direct engagements with the enemy, and I can say with full confidence: in every second of contact, I trusted my guys completely. I just knew they wouldn’t back down. Those seven men were literally crawling under fire, getting as close as possible to the enemy to take the fight head-on.

- Where and when did that happen?

- That was in the Kyiv region, the Kharkiv region, and the Luhansk region. My most recent small arms contact – eliminating Russian troops using a Mavic – took place in the forest near the Chasiv Yar. An Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV) stopped about 50 meters from my position, and Russians began to dismount. On a single battery charge, I managed to drop four munitions. Of the eight enemy infantry who exited the vehicle, five were taken out on the spot. The remaining three moved toward our positions. We realized it was better for us to reach them before they reached us. As the group leader, I made the decision to move toward them. Maybe we got lucky, but the firefight ended way too quickly. When we reached the IFV, we laid down suppressive fire in its direction, expecting enemy contact – but no one responded. Maybe they’d already been taken out by other drone operators’ drops. It turned out to be a "contact" with likely dead Russians.

- Have you ever targeted particularly large assets?

- Actually, we’ve had plenty of hits on equipment as well. In the Bakhmut direction, we torched a Grad system, IFVs and tanks. Around ten vehicles were destroyed on the Kurakhove direction. For us, it became part of the daily routine.

The Grad burned beautifully, with all its rockets cooking off in perfect succession. At that moment, I realized war can have its own kind of beauty, as long as it's not burning on your side.

ONE ENEMY SPECIMEN, UPON SEEING OUR DRONE, TRIED TO PASS HIMSELF OFF AS A TREE — JUST STOOD THERE FROZEN IN PLACE

- What impression have you formed about Russian tactics?

- You can’t underestimate them — they learn fast. Sometimes a bit too fast, in fact. For example, on the Bakhmut direction, they used to launch large-scale assaults with vehicles. It looked like losing over a dozen pieces of equipment in a single assault meant nothing to them. But two weeks later, they switched tactics and started sending in infantry groups instead. I assume either they ran out of vehicles or they realized that in an environment saturated with FPV drones, armored assaults should be kept to a minimum.

- Can you share some examples of smaller-scale encounters? What do you actually see on-screen when closely tracking individual enemy soldiers?

- We’ve run into some pretty special specimens. One of them, upon spotting our FPV, remained standing — apparently trying to pass himself off as a tree in the middle of an open field. Naturally, he died shortly after. Our collection also includes Russians who seemed fond of giving us the middle finger — a few cases, actually. One of them, after our first calibration drop was slightly thrown off by the wind and left him unharmed, assumed that no further drops were coming, he climbed out of the bushes and flipped us off. Then, wounded and bleeding, he crawled back into the bushes – and, to our delight, stayed there.

- What non-combat tasks do you carry out with drones? For example, do you help evacuate the wounded?

- We’ve long adopted the approach that a drone should help with everything it possibly can, especially on infantry positions that are hard to reach. That includes delivery of food supplies, ammo drops using heavy bombers, and we’re working on improving those types of missions.

Once, during the evacuation of bodies and wounded personnel, we used a drone to maintain communication with the group, conduct reconnaissance, and ensure the evacuation team was safe.

- Do you ever get nostalgic about your infantry days?

- Not about the times when I was purely an infantryman — I’m too active to sit around for long. But I do miss the times when I was doing infantry reconnaissance.

- Do you mean literal reconnaissance on foot? Is that an adrenaline thing?

- Because it’s interesting. Maybe it is the adrenaline. You could explain it with a line from a movie: "F#ck yeah, I ended up in a proper shootout with proper guys." Everyone who dreams of going to war and fighting the enemy has that kind of picture in mind: you locate the enemy, you carry out a sweep…

- What operations have really stuck in your memory?

- There was one mission where we were sent into a completely unfamiliar area, in total darkness. It was a tree line under active assault and then we heard the order: "Move the infantry in. Engage. You need to repel the attack." Let’s just say it was pure adrenaline. At that moment, your thoughts just shut off. There’s almost no time for planning but going in without a plan is complete madness. So we took a 15-minute timeout, looked over the maps to get at least some idea of the terrain. Then we linked up with the infantry group and literally stormed into the fight where the enemy was trying to storm us. And there we were, standing tall in the dark, ready to take fire from every bush, while leading the guys to the positions, holding the line, repelling the assault, digging in, catching our breath. And ideally, heading back out again — still in the dark — to pick up the next group and hit the same way all over again.

I don’t really know how to explain it… Sometimes it just feels great. But if you don’t get any rest for two or three days, it gets brutally hard. You start having those "I can’t do this anymore" thoughts. But they pass once you’ve holed up somewhere and caught 3 to 5 hours of sleep.

WE WON’T JUST WALK AWAY FROM THIS WAR

- Your platoon published a message to Zelenskyy, stating that you're ready to keep fighting despite Trump’s pressure on Ukraine and the possibility of losing U.S. support. The situation has shifted since then. But let me ask — do you realize that not everyone in the military shares that stance? Especially given the exhaustion, the lack of rotation, proper leave, or adequate rehabilitation...

- To be honest, I wasn’t speaking for everyone. I was speaking specifically about our platoon. We talked it through with the guys, and we agreed — we still have something and someone worth defending, despite all the issues. Even if the war drags on for another three or four years (the time it might take for a change of U.S. president) we’ll keep fighting.

As for inadequate leadership, Ukraine has plenty of systemic problems. But we also have enough young, ambitious guys who know exactly what they’re doing in the field and how to act. It’s those who’ve actually been through the war, not just military academies, who need to be given command. If someone’s been in the infantry and lived through ten assaults a day on their position, they’ll think very carefully before giving any order.

For those serving in brigades where they’re not valued and are given the most senseless orders, there are currently options in Ukraine to transfer. We need to understand that we’re not going to just walk away from this war — like, "I’m sick of fighting, so I’m out." Based on that, you need to treat it like a job: if you don’t like it, or if the pay isn’t worth it, then find a different one — one that fits you and actually lets you do your job with meaning.

- How do you cope mentally with the loss of fellow soldiers?

- Everyone in our unit has been wounded at some point, but we haven’t had any KIAs. There was one severely wounded who had both limbs amputated. How do you deal with something like that? Like with any other challenge in life: you need knowledge. We train as an entire unit and regularly review tactical medicine. Every brother-in-arms knows exactly what to do in case of a specific injury — we have a clear response algorithm. I’m convinced that all servicemembers must keep learning. While we're at war, we’ve got no spare time — let alone to piss it away, pardon my French.

- So you study psychologists’ recommendations both in theory and in practice...

- No, we just work. To put it bluntly, over three years of war, our battalion has cumulatively spent only about three months on recovery. And even then, instead of treating recovery as rest, we scheduled a full training and education program — Monday through Saturday, with only one day off. We actively sought out people who could teach us, and on our own initiative acquired the knowledge that would help us in the future.

When it comes to psychology, nothing works better than the atmosphere within your unit. These are the people who are with you 100% of the time. If you’ve created the right mood and can freely joke about death, fully aware that it could happen any second, then morale on the front line will be solid.

Our former commander once said something brilliant: "We’re not here to die for our country. We’re here to kill for country." That’s exactly the mindset you need when heading to your position — you go there to kill, not to die.

- I’ve formed a certain impression of you. It seems like you’re ready to make war your calling, even after victory. Is that the case?

- As of now, I’ve been serving as an officer for six months, but I wouldn’t want to keep fighting after the war is over. And there’s a major reason for that. If the war ends and we shift to a contract-based army, I’m not willing to serve in a military that still trains using manuals from the 1950s and 60s.

- So you don’t believe the army will change — that generals and officers will learn from this war going forward?

-This war is already being studied. The world has seen a surge in the technological training of our soldiers, and that will be analyzed for years to come. But I don’t believe in quick change. Reform has to be ruthless. A good example is the police reform. If you want to change everything, you have to throw out the old system entirely and start from scratch.

But when we throw out half and keep the other half, including commanders who spent their whole careers taking bribes — and put them back at the top, then nothing will really change.

I do believe our army can be reformed and made the strongest in the world. But I’m not sure I’d want to be part of the military after the war ends. I did my compulsory service once, and for me, the army outside wartime just doesn’t hold any appeal.

- How do you react to negative news from the rear, particularly when it involves servicemembers? For example, incidents like a soldier being beaten up by teenagers. These are isolated cases, but how do they come across from the front line, through your own experience?

- It’s a reminder that none of us are perfect, whether we’re in uniform or not. Division within the country during wartime is the worst thing that can happen. I’m not ready to vouch for all servicemembers, just as I wouldn’t vouch for all civilians.

A certain shift in public attitude toward the military, which we’re now starting to feel, is to some extent understandable. Many people say they’re tired, and the military keeps asking for money for supplies. Ultimately, the story of a 30-year-old man hiding from the TCR (Territorial Center of Recruitment and Social Support - ed.note), saying "this isn’t my war" — sure, sounds nice but...back in 2022, I didn’t go to the draft office for one simple reason. I knew that the wonderful story of me going off to war would get seriously delayed because at the time, the lines at the draft offices were insane, and everyone understood exactly why they were there. Now the trend is gradually shifting in the wrong direction. And that shift depends on society itself. People need to understand that it’s the soldiers who take the risks so that civilians in their towns and villages never have to learn what war truly is.

Olha Skorokhod, Censor.NET