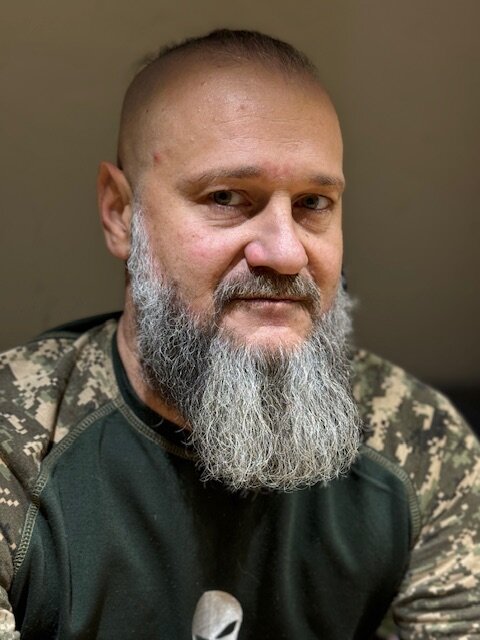

People’s Hero of Ukraine Oleh Davydenko, call sign Chub: "People pay to leave army. And I want to go back!"

It feels as if this man had been restoring his severely injured arm, wounded back in 2014, specifically for the full-scale invasion, just to face the enemy in battle once again. During the fighting for Bakhmut and Kreminna in 2022, the volunteer fighter-paratrooper was wounded again. Although he has been officially deemed unfit for military service, he now works as an instructor and is determined to return to the army.

There may not be an official term like "volunteer fighter-paratrooper," but the war that has been raging in our country for over a decade has brought many new definitions—both for soldiers and for those who support the army. For Oleh Davydenko, a native of Zhovti Vody, things are simple: in 2014, he went to war as a volunteer with the OUN unit. After his first rotation, he decided to formally enlist in the army and joined the 25th Airborne Brigade. So calling him a volunteer paratrooper is more than fair. Especially now—after being discharged from the army due to multiple injuries—he still stays close to it by choice, training newcomers in everything he knows. And he knows a lot.

Back in 2015, Oleh Davydenko received the highest non-state award, the "People’s Hero of Ukraine." Since then, he has repeatedly proven this high honor through his actions.

"I WAS THE FIRST FROM THE VILLAGE WHERE I GREW UP TO GO TO WAR."

- Why did you join the OUN specifically in 2014?

- The military enlistment office couldn’t find my file. At that time, I was trying to enlist everywhere, I applied to Azov, to Donbas... but they said, "No, you have a clean military record — goodbye!" Later, my aunt, who worked at the enlistment office, told me, "When they moved the office from one place to another, they burned Kamaz trucks loaded with the files — yours was among them..." I kept monitoring the internet and saw the volunteer battalion OUN. OUN-UPA means a lot to me spiritually. I called them, and they said, "No questions — come on over." I told my father where I was going, and he said, "It’s your decision — go ahead. Everyone in our family has defended Ukraine. That’s what I taught you. I don’t want this war, but what can you do." No one believed I would actually go to war. But I turned around and left. It turned out I was the first, the very first, from the village where I lived.

- I understand that the Maidan somehow influenced your decision to go fight…

- I wasn’t allowed to go to Maidan; I only watched it on TV. My father wouldn’t let me: "I know you. If you go now, everything will start burning and exploding there." My mother passed away a long time ago—27 years ago… So it was just me and my father. When Kyiv started burning and exploding, I said, "Now I’m going!" He replied, "Don’t go, because they’ll start shooting." They started shooting—I said, "It’s time to go," but my father said, "There’s nothing for you to do there anymore."

In Nizhyn, we quickly completed training and later ended up in Pisky. It was late August. The fighting was already happening right in the village. That’s where they shot down an Il-76 at Luhansk airport with 25 people on board… I became head of reconnaissance for the battalion. I picked my team and started training them… But we went to war unarmed: for 20 men, we had four assault rifles and one RPK (laughs). They told us: you’ll get everything you need in battle.

I clearly remember the first reconnaissance mission. Tank crews from the 93rd Brigade were stationed nearby. It turned out no one was prepared for the conditions we found ourselves in. Everyone was freezing. So we went searching through damaged houses for blankets and throws. I set one strict rule: God forbid anyone enters a fully locked house — I’ll tear their head off! Back then, we all hoped: we’d quickly crush the enemy, people would return home, and the state would compensate for the damaged houses. Myr Street in Pisky looked like this at the time: one side intact, the other terribly damaged… Some places were hit, some had no windows, and doors had blown off... We grabbed as many blankets as we could and returned. One guy, who later served in my recon team, suddenly decided to lecture me: "I thought you were normal, but you’re a looter!" I replied, "Well, a looter is a looter." I distributed everything to everyone. Then, at night, he came back: "Chub, you’re not a looter, give me a blanket!" I said, "No, no, looter!" (laughs.) That was my first sortie.

There in Pisky, we acted at our own risk, doing bold things—going behind enemy lines, carrying out sabotage, planting mines... Back then, the war was almost on a schedule: before noon, the enemy slept; in the afternoon, when it wasn’t too hot, they worked in their gardens; and all night we fought them.

- In their gardens — literally?

- Yes, literally in their own gardens.

- So, these were locals?

- Locals. The Moskals came later.

- Did you ever get into the airport?

- That was already in the fall. Our unit went in there. When they asked, "Who will go to the airport?" I obviously volunteered. But the unit commander said, "You’re leading reconnaissance; you’re not going anywhere." Soon, our constant support was needed for those in the terminals. At the end of September—early October, when the deals started, they set the condition to enter the airport with no more than four magazine cases. We smuggled ammo and water past enemy posts to our fighters. They were amazed: "Where does all this come from? How do the guys have what they need to fight?" The longest I stayed at the airport was a day and a half. We just couldn’t get out, and we fought there alongside all the guys. Otherwise, we crawled in there every day or every other day. Besides our own tasks, we delivered everything necessary.

We crawled past their positions on our bellies, stealthy like scouts. Now I realize how risky that was. Back then, it felt like playing war games. There wasn’t such dense minefields or vigilance from their side. We bypassed them, slipped behind their lines. Once, the three of us even entered Donetsk itself. We changed into civilian clothes and walked into the city. The only things we had with us were knives and grenades. Nothing else.

"I GOT MY FIRST WOUND ON MY BIRTHDAY."

- Why did you decide to go to Donetsk?

- I wanted to see how they had everything set up. I was desperate! Reckless. Now, when I remember it, I get goosebumps… An idiot! I even managed to enlist with their militia! I did all this knowing well that they didn’t take volunteer fighters as prisoners. And I left them on a page the size of A4 an image of my wolf with the caption "Greetings from Chub." They understood that OUN members had come. That’s how we intimidated them. Even if we didn’t do anything, we still left greetings.

We had a guy with us, callsign Monk. Once he told me: "You’re not just Chub." — "What do you mean?" — "You have three big letters — CHUB: polite killer of scum." That’s military humor. Because the guys kept telling each other how during hand-to-hand combat in enemy trenches, I said: "Sorry, but you came here yourself." Monk was surprised: "You still have time to apologize?"

There in Donetsk, we got exposed exactly when we were signing up. My long chub (traditional Ukrainian haircut - ed.note) was hidden under a cap. When I was signing, like a polite person, I took it off. Not only did I have long, Cossack-style mustaches, but my chub fell out too... I had to jump into hand-to-hand combat, throw a grenade, and withdraw. We spent 15 hours getting out. They chased us through the fields, mobile groups were searching for us… We got home, and there were three shot glasses with bread on the table… (laughs.) We came in, and the guys were sitting gloomy. "Who’s this for?" we asked. They said, "For you!" They’d heard the interception, heard the shooting — from edge to edge. When we went on missions, I always planned the time accounting for all emergencies, and we usually returned more or less on time. But here, plus 15 hours, that’s a lot… So the guys got upset.

Our main task on that sortie was to probe their defenses, find where to strike, how to get into the city. We thought they’d bring us ammo and weapons soon, and we’d go on the offensive to push them out. Basically, until spring 2015, it was possible to enter Donetsk without much trouble. If the Armed Forces of Ukraine had really engaged and blockaded Donetsk back then, we would have taken it.

It was in Pisky, on my birthday, that I got my first wound. It was October 11. We were preparing an operation together with the Main Intelligence Directorate (DIU). Their commander, Mr. Advokat, sadly died in spring 2022. He was my friend, my comrade. He came to Pisky to prepare the mission and gave us preliminary intel on what needed to be scouted and learned. He called: "We’ll come and congratulate you on your birthday…" And we were planning to put on a fire show. Everyone agreed we’d hit the enemy hard. The 93rd promised to send "cucumbers" (mortars - ed.note). Meanwhile, we mined their warehouses. We strung about five and a half kilometers of detonation cord, because we had nothing else for the explosion.

And then the guys brought me a rocking chair… They started the generator, ran an extension cord and two wires to me: "Chub, let’s go!" At exactly 12:00—shoo-oo! Everything lit up beautifully. But we didn’t know that a humanitarian convoy had just arrived on the other side. Two hours after our show, an insane shelling began. Later, when we captured prisoners, they said, "We didn’t even register what they brought us, they just loaded it straight from the trucks into the guns and fired at you." It was terrifying what was happening…

That day, the guys from the "Crimea" hundred promised to make pilaf and lamb kebabs. I said, "I don’t eat lamb." — "I’ll make you eat it anyway." Considering we’d been surviving on canned tuna for a month and a half, any food was a joy. They brought us a "Gazelle" full of tuna — that was all we had. Only recently did I start eating canned tuna again. Before that, I couldn’t. A month and a half with no bread, nothing, just tuna — six cans in a pack, morning, noon, and night. And then meat… I said, "Alright, let’s go." I got stuck in the first house on the frontline and couldn’t get out because of the shelling. They called me: "Chub, come on, the pilaf is ready!" Imagine this: four houses down, there’s no war anymore, practically nothing is hitting there, but where I was, everything was falling apart. "Come on," they said, "run over!" I ran, hearing them shouting "Get out." I thought I’d make it. I didn’t…

It hit from the "Vasylok." Four shells in a row — boom, boom, boom. Those watching from across the street said, "We thought you were done for because you were flying like a frog…" Two fragments hit my back, two hit my shoulder. The fragments went under my armor, ricocheted off the inside of the plate, and then entered my back. That’s what saved me, because if they had gone straight through, I’d be done for — it would have hit my heart area. I got up, realized I’d lost my bandana — found it. Grabbed my rifle and crawled on. One fragment also tore a vessel in my nose, so blood was streaming from my nostrils… I ran to the guys, Fakir shouted, "Chub’s wounded! Chub’s a WIA!" The guys started checking me out. I said, "It’s nothing serious." — "You’re in shock!" — "It’s fine, just my back hurts." — "Where’s your armor plate?" — "I don’t know." It turned out the armor plate was gone from the back; I found it the next day.

- What do you mean — the next day? And the hospital?

- What hospital? The medic from the 93rd Brigade showed up. It was his birthday too. He examined me and said, "It’s my birthday today." — "Mine too," I said. "Oleh." — "Oleh Olehovych," we introduced ourselves. "Well, you need to go to the hospital." But our rotation was scheduled for October 19. Just about a week, and I’d be heading home. I had surgeon friends there who would fix me up and stitch me properly. That’s what I decided.

In the morning, we gathered for reconnaissance, heading out at five o’clock. I found my new body armor plate. When we came back, our unit commander was waiting and shouting, "How come you didn’t report your wound to anyone?!" — "Well, the mission had to be done, it was planned. Nothing torn off, no heavy bleeding — so, whatever…" — "Straight to the hospital!" So, we arrived at the hospital in Krasyk — later renamed Pokrovsk. I was with a guy callsign Khan; two fragments hit his nerve endings, one in his arm and one in his leg, and he was shouting non-stop. The hospital was full of wounded. Then a doctor came out, looked like a baby doll, and said, "I have only one ampule of lidocaine left, no painkillers at all. Does anyone have any pain medication on them?" — Where from? It was my turn. I said, "Give my comrade lidocaine." So, they treated and stitched me up without anesthesia. The only warning I gave was, "I’ll be talking." — "Alright." I kept cracking jokes until the doctor asked me to stop, saying, "My hands shake when I laugh. Tell me something else." I said, "If I shut up now, I’m gonna piss myself — it hurts that much." He said, "The main thing is, you’re enduring it." He removed those two fragments from my back. I asked, "Can I have the bottle from the penicillin? I’ll send it home to my father. I’ll fill it with oil so they don’t rust…" I kept all my fragments from various wounds. When I tried to get up, he said, "Wait. Show me your undershirt." I took it off, and he said, "Go get photographed again." — "New undershirt?" — "It was new." — "You’ve got two more holes." He found two more entry wounds on my shoulder. Looking at the scan, he said, "I can’t get those. They’re lodged in your joint; I can’t reach there." They wanted to send us to Dnipro, but I refused — and the guys took us back to the unit. Only after we were rotated did I go to the hospital at home. They removed my stitches — but everything opened up again. The operating nurse stitched me up again and then came to my home to do dressings and care for me. If you don’t count her as my second wife who was visiting my third wife, whom I was married to at the time, you could say everything was fine.

"GIVE ME A JOB THAT DOESN’T REQUIRE USING MY HEAD OR HANDS"

- During the rotation, my brothers-in-arms and I decided to "surrender" ourselves to the Armed Forces of Ukraine. We enlisted through the Brovary military enlistment office. My younger brother had just received his draft notices. Our father called and said, "Keep my younger son safe, take him with you — you’ve got combat experience." That’s how we all ended up in Desna. During assignment, there was a bit of arguing — everyone wanted to join the unit closest to home. In the end, two of them went to the 95th Brigade, and four of us, to the 25th. My brother and I served in a reconnaissance and airborne company. In 2015, we were deployed to the Avdiivka sector. In April 2016, we were demobilized. During that rotation, my right arm stopped working.

- Because of the fragments in the joint?

- Turned out, the arm had been partially torn off — it just held together for a long time thanks to my good physical shape. Then, all of a sudden, the shoulder started dislocating. I went through every painkiller the brigade had in a week — swallowed and injected all of it. The brigade medic, Slavik Prokhorov, said: "This can’t go on." And sent me for treatment. After the scan that revealed the fragments, nobody did anything else. And during the draft medical exam, no one paid much attention, even though I had adhesive strips on my back stitches, and they were still seeping…

I was sent to the hospital in Irpin. Slavik Prokhorov came to visit me and, let’s say, was surprised to find out I wasn’t being properly treated. After he had a showdown with the doctors, they scheduled me for surgery. They didn’t remove the fragments because you can’t grip them with an arthroscope. But the surgeon said: "Whatever was broken — I screwed it back in place. Whatever was torn off, I reattached it. Whatever was ripped — I stitched it up."

- Did it take long for your arm to recover?

- It did. It started to wither… After I was discharged, I went back home. I was living with a second cousin — I had just gotten divorced. My cousin was a fan of "the stuff," actually not just a fan — a pro. Every day: "Come on, let’s have a drink. Let’s drink…" I kept saying, "No, I don’t want that. I’m not doing it."

- Good thing you didn’t get pulled into it.

- I did get pulled in… Eventually, it got awkward for him — didn’t know where to put me. My father and I had our own woodworking shop. I came in, turned on the machine and realized I couldn’t do it. The sound drove me mad. Everything squeaked, buzzed, whined — I’d start twitching, panic would hit.

There was nothing to do. The money I got from the army ran out quickly. The local administration gave me a dorm room — just a small room. Basically, another barracks. I slipped into depression…

I wouldn’t leave the place during the day — didn’t want to see anyone, because I was sick of the constant, "So how was it?" The only thing I could say was, "Go see for yourself…" Either they start pitying you, or interrogating you. I’d go out at night to the 24/7 store, stock up, and then drink through the whole day.

One day, my comrade Klyk (also no longer with us) called me and said, "Commander, I’ve had it with you. I call you at night — you’re drunk. I call in the morning, drunk. Afternoon, evening — drunk. Are you ever sober?" — "Screw you!" I said. But he didn’t give up: "Listen, there’s rehab for your arm. How is it doing?" — "Don’t even ask." I couldn’t even scratch my nose. I had to do everything in the bathroom using only my left hand. I felt like that was it — life was over. Thoughts even crossed my mind like: maybe I should hang myself? But then I’d think — I can’t even tie a noose with one hand. And then there was my child. She saved me. My daughter kept coming to see me. We’d go places together. Those were the moments I stayed sober, running on emotions. Klyk invited me to Kyiv. I only had enough money for a round-trip ticket. He said, "There’s food here, a place to stay." So I came. And it really was good rehab.

Olia — a volunteer — started visiting me regularly. We had met before, back when I was operated on in Irpin. She kept calling, checking in on how I was doing. But it was a tough time for me, and our relationship didn’t go any further back then. But now, crazy love. And then I got discharged — cue the sorrow. I had to go back to the dorm, and she was staying in Kyiv. Olya said, "Why go back? Stay with me." So I stayed. But my arm kept withering, it got shorter. We found another doctor to take a look. He agreed to operate on me. We even raised the money for the surgery pretty quickly. Surgeon Maksymets reattached my shortened bicep in a way that stabilized the joint. There were a lot of procedures, the operation took a long time. Afterward, the doctor told me: "For ten months, you don’t stretch the arm, don’t use it at all. No push-ups, no parallel bars, no throwing — forget all that for life." So I did as told for ten months. Then, little by little, I started training again. One day, Maksymets caught me doing pull-ups on a workout bar — we lived nearby, and he saw me. He scolded me right away: "Why did I even put you back together? So you could ruin it again?" I said, "Mikhalych, look — everything’s fine. I can do this." He sent me for tests — he couldn’t believe it himself that the arm was working. He even recorded a video. Then he asked me: "Write down how you recovered. I forwarded your case to the States — that’s where I learned to do that surgery — and they don’t believe you recovered like this. I told them: he’s a recon paratrooper. Our fighters can do anything."

In 2016, I started working at "Cascade-15," a military-patriotic training center. They hired me as an instructor thanks to my combat experience. We traveled to military units, training young guys. But in 2019, our funding was suddenly cut off. The new president started saying there was no need to prepare anyone, that we wouldn’t be fighting anymore — all that "shashlyk-mashlyk"...

I went through all the medical boards and in 2020 was officially granted disability status. Third group — 50% loss of work capacity. The fancy certificate reads: "Assign work that does not involve using one’s head or hands."

- And why can’t you use your head?

- Because of concussions. I asked the commission members, "What am I supposed to do then? Ride a stationary bike for someone else?" — "Well, with your conditions… sorry." There was another thing: everyone expected I’d be assigned second group disability, because of the arm. But no one knew I had restored it; according to the paperwork, it didn’t work. But I hadn’t recovered it for people or commissions — I did it for myself. When I got the paper, I asked: "Why third group? Why not second?" — "Well, if you had paid three thousand…" — "Three thousand what?" — "Three thousand hryvnias." Olia said, "I’ll give you the cash right now." — "No, the document’s already processed. Come back in a year, and we’ll get it sorted." That was in 2021. And in 2022, the full-scale war started — I didn’t need to go anywhere anymore. I was already fighting.

"NEAR BAKHMUT I TOOK A FRAGMENT THAT BLOCKED AN ARTERY. DOCTORS CAUGHT IT FOUR CENTIMETERS FROM MY HEART"

- Where did you go in 2022?

- Back to the 25th. On February 24, around noon, the company commander called and said, "Chubaka, come on — I’ve got three spots: for you, Mamon, and your compadre. Get here fast!" I arrived in the village of Tymofiivka near Ocheretiane, not far from Avdiivka. On March 20, I got my first wound in this war — at the location we called "Tsar’s Hunt." We came there to work as a sniper pair. A platoon commander was supposed to come and pick us up. Everything had been coordinated with the battalion commander and the company commander — where we’d work, who we’d report to. "Alright," they said, "the platoon commander will be there soon." And then the radio operator announced over comms: "Come quickly, the snipers have arrived." I cursed him out. Who the hell says that over the radio? We stepped outside with the company commander to smoke — and suddenly a 120mm mortar round landed right next to us. Good thing it was a delayed-action round. The company commander caught shrapnel in his shin, and I got two fragments in my lower leg and two in my thigh. We crawled back into the basement.

The shelling starts… A medic runs in: "What’s wrong with you?" — "Eh," I say, "just a concussion." Blood was pouring out of my boot! Damn, I screamed that time! And not just me. They had just given me a new Columbia thermal underwear. I said, "Don’t cut it, I’ll take it off myself. Just don’t cut it! I’m fine, I’ll do it."

At that point, the enemy was hitting hard at the industrial zone. Constant shelling. They had the upper hand. They were trying to launch assaults. That’s why I’d been sent there — I came with a 50 caliber to stop lightly armored vehicles. They were trying to push in along the road, and I was supposed to stop the convoys. But fifteen minutes later… The commander had dropped me off and left, and then suddenly they radioed: "Come back, Chub’s a WIA." He goes, "What do you mean?! I just left!" But a week later, I was back on the front line. All the fragments went through soft tissue. No bones were hit. I spent two weeks helping with replenishment and then snuck back to the front line for a week. They even put out a search for me. The commander laughed: "I got a letter from brigade HQ — why isn’t your sergeant showing up for his wound dressings? I told them to check the reports — you were on a combat mission."

Then we were sent to Bakhmut. We spent the entire spring and summer under Bakhmut. And in early autumn 2022, we took part in the liberation of Izium, after which we were redeployed to Lyman and Kreminna. It was near Kreminna where I had a run-in with a tank. Around October 20. Yenot, our company commander, tasked the snipers with covering assault groups. So we went out to carry it out. But the Russian tank was firing wherever it pleased. My partner and I were moving ahead, with Redys out front using a thermal imager. We were scanning the area, choosing a position, shouting to each other. The shelling continued, but the tree line we were in offered decent cover — slightly elevated terrain. The tank kept firing blindly: something exploded over here, then over there. Long story short, a round went off right between us. Thank God it wasn’t a high-explosive fragmentation shell — it was armor-piercing. I slammed my back against an oak tree and blacked out for a moment. But I came to, we kept going, finished the job, covered our guys, and made it back. That’s when the rain started — and we were constantly soaked. The guys found a beekeeping shed to sleep in, but the basement was flooded… We all slept in water. No way to warm up, no way to light anything. The generator was only running to keep the Starlink online — so we had comms. In the morning, I couldn’t get up — my body was all cramped up. They pulled me to my feet, but I couldn’t walk. That’s when my partner told me about the shell. "Why didn’t you report it?" "Well, we were all in one piece. No one’s counting concussions anyway." They sent me to the hospital. Concussion, back injury. I was first taken to Dnipro, then transferred to Kyiv, where they put me in the ENT unit to treat the concussion. They sent me for a chest X-ray. The radiologist said, "Take off your cross." I said, "I’m not wearing one — I took everything off." She said, "Well, congratulations — you’ve got metal in your chest." "What do you mean? From where?" Only after they cut me open did they tell me where the fragment had lodged. And only then did I remember when it could’ve gotten there.

- Was that an old piece of shrapnel?

- Yeah, I caught it near Bakhmut, just didn’t know it. A six-by-six chunk got lodged in my pulmonary artery — like a little cube — completely blocked it. The surgery lasted ten hours, they cut everything they could to get to it, finally caught it four centimeters from my heart. So now I’m breathing with one and a half lungs — not exactly convenient. But I’m getting used to it, doing diver’s breathing exercises to stretch my lungs.

Then they started looking at my back: "What’s that — just a bruise? There’s nothing there." And by that point, I was already dragging my legs behind me. On top of having my chest cut open, I couldn’t even walk properly. A friend got me in to see neurosurgeon Pechyborsh at the border guard hospital. He took one look at all the scans and said: "You’re mine." He operated on my back and told me I’d need another year and a half to recover. For six months I couldn’t sit — only stand, walk in a back brace, or lie down without one. At the military enlistment office, they told me: "We’re going to discharge you — you’re unfit." But the neurosurgeon who was doing my medical evaluation wanted money. He said: "You’re faking it. People walk the next day after a surgery like that." I replied: "Either you don’t know what you’re talking about, or you want something." Sure enough, he wrote it down on a slip of paper — five thousand hryvnias in cash. But during my next visit, he changed his mind. Explained: "I saw that your military specialty is high-risk." – "Ah, you realized I’m a sniper?"

But I asked them not to discharge me. The pulmonologist even got curious while reading my file. And I said, "I need to keep serving. Take me out of the Air Assault Forces, put me in the infantry if you have to." – "Who operated on you?" – "Professor Hetman." – "You’re lying!"

I said, "No, Professor Hetman." So he calls the professor, addresses him formally, and Hetman says he remembers me. Then he asks, "What does he want?" – "To keep serving." – "Discharge him, for God’s sake. There’s nothing intact inside him. All his arteries are shredded. Discharge him!" They talked a bit more, and then the doctor says, "Come with me." He made me walk up to the third floor. I got through two flights of stairs and started gasping for air. That’s when he asked, "Now do you understand?"

The discharge process took three months. One certificate after another, on top of more certificates…

- But after the discharge, you were involved in civilian demining…

- That was initiated by the Sheriff holding company. We built everything from scratch, but they simply stopped funding us. The state said it wasn’t going to reimburse a private company for its work — even though we had bought about a million dollars’ worth of equipment and machinery. The government was supposed to reimburse 70 percent, but instead they said, "Goodbye, go take a hike." Those $300 million allocated for demining? They vanished somewhere — now they’re just gone. And yet, in our country, we have enough land to demine for the next 750 years.

- I take it not everything has been cleared in Kyiv region, or in Zhytomyr region either?

- Nowhere near it. For example, we took on a plot — part forest, part field, part pond. And get this: some of our entrepreneurs somehow managed to sell about 50 hectares in Mykolaiv region to the Germans — an area where there had been active fighting. Brilliant! The Germans moved in, one of their combine harvesters hit a mine, and they immediately filed for demining. There’s at least five years of work there. And that’s not even counting the seasonal issues — in winter, frost stops everything; in the rain, sappers can’t work either. And as it turns out, the government isn’t even interested in this...

- But you’re currently doing instructor work, right?

- Yes, with the 48th Special Purpose Detachment. So far, we’ve only agreed on training sessions. But at least give me a chance! I immediately told the commanders: if I don’t keep improving my combat experience, I won’t be able to teach the rookies anything. How was it in the Soviet army? Who was an instructor? Someone who couldn’t do a damn thing and knew nothing. But that’s not me. The commanders say, "You’re clever!" — "I’m not clever, I’m objective." "We’ll see," they replied. I’m ready for anything. People pay money to get out of the army. And I want to go back!

Violetta Kirtoka, Censor.NET