Commander of "Dovbush’s Hornets," call sign Liutyi: "We have many ideas for using various types of drones. But we need people for that. And we need them now"

Major Viacheslav Shevchuk, call sign Liutyi, belongs to the category of commanders who speak about their own path in the war only as a last resort. Only if a journalist specifically asks. But when it comes to various aspects of the war, relations with his soldiers, or reforms in the Armed Forces — he is more than willing to talk.

And also about UAVs — because in the 68th Separate Jaeger Brigade named after Oleksa Dovbush, Viacheslav heads the battalion of unmanned systems. The unit is called "Dovbush’s Hornets." By the way, the battalion dog, a calm and well-mannered corgi, is also named Hornet.

Despite his call sign, Liutyi speaks about his soldiers with warmth and respect. As for his command philosophy, he says: "I once had a few good instructors at the military academy. One of them used to say: ‘There are no bad soldiers, only bad commanders.’ Every person has strengths and weaknesses. You need to focus on the strengths and work a bit on the weaknesses."

This conversation took place in a Kyiv café. We talked about issues with the supply of drones and their components, as well as how service is structured within "Dovbush’s Hornets." What was once a UAV company has now grown to the size of a full battalion. Liutyi and his Hornets are in need of new personnel, both for specialized positions and a wide range of others. During the interview, Viacheslav explained how recruits in his battalion can gradually find their place in this war, depending on their skills and ambitions.

We started the conversation with the operational situation at the frontline.

- You’ve just returned from the Pokrovsk direction. What’s the nature of the fighting in the direction where the Dovbush Brigade is operating?

- Over the past six months, we’ve managed to stabilize the front line. We’re holding the defense directly in front of Pokrovsk. The enemy is no longer making gains there. We haven’t lost any positions, we’re holding steadily, give or take. The enemy’s assault operations are no longer as intense as they were a year ago, back then, near Avdiivka, we were facing 100 to 200 enemy troops storming us daily, with countless assault attempts. Now, it’s 10 to 20 occupiers advancing at a time. Recently, they tried to flank us from the direction of Kotlyne; then, they were tasked with advancing by May 9, but they still haven’t broken through and are now trying to bypass us via Myrnohrad. They want to take it in order to control the supply routes to Pokrovsk. Pokrovsk is a high-priority target for them, they were supposed to capture it back in December. It was a mega-objective, but they failed.

"EW SYSTEMS DON’T WORK AGAINST FIBER OPTICS. YOU CAN’T DEFEAT FIBER OPTICS LIKE THAT. EVERYTHING MUST BE APPROACHED COMPREHENSIVELY."

- We’ve got the broad-brush picture of the fighting, now let’s move on to your battalion. We won’t name the manufacturers whose UAVs are in service with Dovbush’s Hornets, because the enemy is interested in this as much as possible. But we will ask: what drones does your opponent use?

-The enemy has stockpiled a significant number of fiber-optic drones. And they’ve proven to be highly effective — because they can’t be detected via video interception, and they can’t be jammed. The connection runs through fiber optics. It’s basically like a fishing reel with a line. As the drone flies, this little reel slowly unwinds. Both the video feed and control signals are transmitted through that line. For us, it’s crucial that a drone stays within radio line of sight — either with the ground station or a relay transmitter — so it remains in visual range. We can’t fly behind a building, for example, because we’ll lose the signal. But a fiber-optic drone can fly into a building…

- What is the maximum range of your drones?

- The length of the reels varies. On average, the optimal, and what we currently need, is 15 to 20 kilometers.

- And what about theirs?

- The same. On average, they use reels of ten, fifteen, and twenty kilometers.

- Last year, the military was strongly requesting electronic warfare measures. Has fiber optics changed the situation?

- Yes, EW doesn’t work at all. You can’t defeat fiber optics like that.

- So what’s the solution for dealing with these EW systems?

- Use them in combination. Everything has to be comprehensive. Besides, fiber optics are very vulnerable. Sometimes a drone takes off — and then the line snaps; either it got damaged somewhere or caught on something because of the wind. Weather conditions also affect it: you can’t always fly a fiber-optic drone. There are limitations. But radio drones don’t have such critical restrictions. So it’s a combined effort, and different countermeasures are needed.

- What’s the approximate ratio of enemy FPV drones to ours in your sector?

- You can’t underestimate the enemy. They have everything militarized. Russia exists for war, for aggression. They’ve always produced these. They will always have a surplus of ammo, explosives, and drones. And drones are the most relevant weapon in modern warfare now. Drones decide the outcome of the war.

- There’s plenty of footage online showing a drone hunting down a single enemy soldier. Is such a ratio acceptable for you as well?

- Of course, it is. We need to eliminate the enemy by any means necessary. Using one FPV drone per enemy is absolutely normal. Sometimes, even several are used, because there are obstacles that need to be destroyed

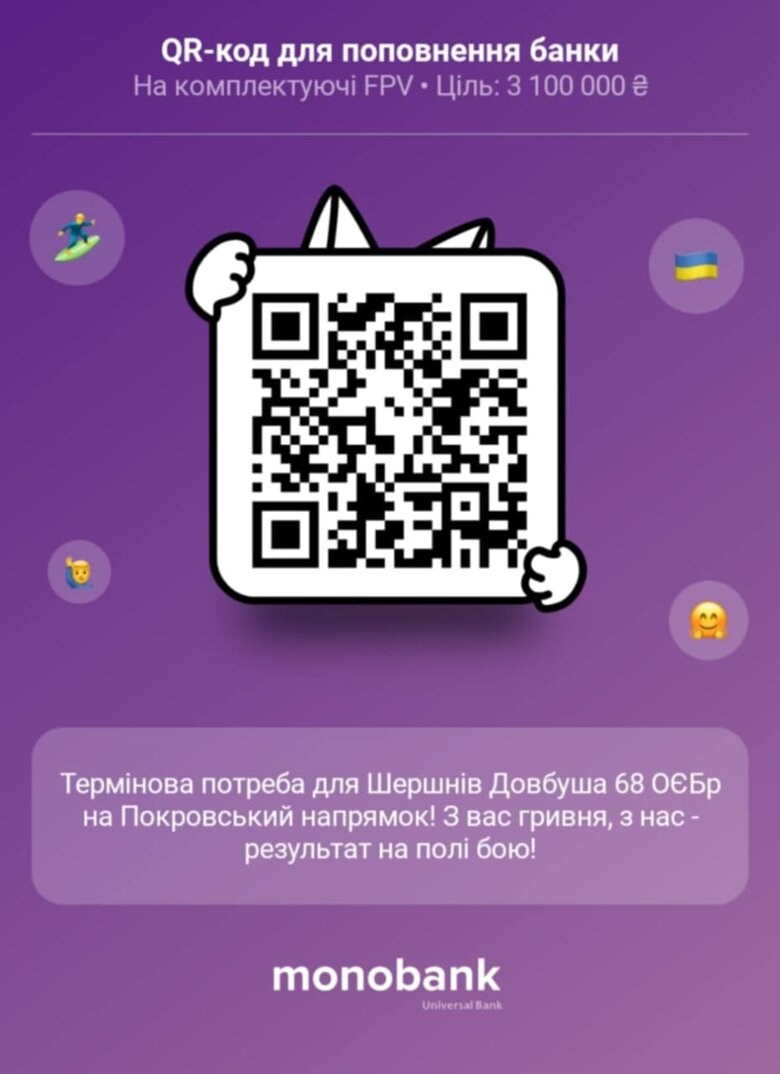

To maintain this resource, we invest a lot of our own funds. In a single month (and I’m not ashamed to say it — the guys all chip in), our unit — back when we were still a company — spent up to ₴3 million from personal combat pay alone.

- Wow. Am I correct in understanding that this is also necessary because nearly 100% of the drones supplied to you aren’t ready for immediate use and require modification?

- I’ll put it this way: that’s your wording. And I won’t deny it.

- And what about our own fiber-optic setups? How good are they?

- Right now, the quality is very low. We’re only starting to get a feel for all this. Some manufacturers produce better fiber that has a lower break rate and fewer signal losses. With others, the line snaps as soon as the drone takes off.

So for the moment everything is in test mode but the capability already exists, and we’re beginning to work with it. And that’s great.

- I risk sounding like an armchair critic here, but let me ask: why is it still in test mode? It’s been clear for quite some time that this is the direction things are heading. Of course, the question isn’t directed at you — I’m just curious to hear your take.

- We learn from our mistakes. People assumed that as long as radio-controlled drones were working and we could find frequencies to operate on, no one would… But now we’ve had nearly six months of a static front. And they keep bringing in new electronic warfare systems, more EW units, new setups. And it’s becoming very difficult for us to operate.

- And reality itself is forcing both sides to develop fiber-optic solutions.

- Yes, that’s inevitable. You could say it’s a 100% strike capability. It may have its limitations, but it will hit the target regardless of the enemy’s EW activity.

- Continuing on that note. In February this year, one of the Hornets' pilots, call sign Luh, wrote and Censor reprinted a bitter, critical, perhaps angry or disillusioned post about the screw-ups with the cameras that often come with the drones supplied to the Armed Forces by the state. Here’s the quote: "There are companies that install really sh*tty cameras on their drones. Because we have ProZorro, we have tenders. And if you put the cheapest camera in there, the state will definitely buy your drones. And pilots will definitely suffer and struggle, and lose drones, and fail to complete combat missions, and not kill Russians. And Russians will kill us instead."

Three months have passed. Has the situation changed? Maybe the percentage of sh*tty cameras has gone down? I can tell from that sarcastic smile — it hasn’t.

- Luh is the senior sergeant of our battalion. He’s my tower of strength. As for the camera screw-ups... There are issues with some drones that are actually pretty easy to fix. I’ll even say this — one manufacturer came to visit, I won’t name them, and we told them: "This component right here? We don’t need it. You can take it out and save money." And they said: "Well, it’s already built in — what are we supposed to do with it?" Like... only business.

It wasn’t a media conversation. He said: "What am I supposed to do with them?" – "Well, we don’t need them either…"

About cheap components. You see, even antennas can be simple and much cheaper than the ones we’re being supplied with. Sometimes, you can find more cost-effective solutions. But they just don’t want to.

Next. We can use the same base, camera, good motors, the frame — the parts that are constant and don’t need to be changed. But what we do need, video receivers and some form of control link, has to be upgraded. And this is where the worst part begins. Because no one pays attention to the need for these changes. They go ahead and sign tenders, say, for a thousand units of this type of drone. We take them, sure. They work for us, so we take them. But after flying just 10 of them, they’re no longer operational. The enemy saw them, analyzed them, and started jamming them. That’s it. We have to adapt. But they tell us: "Well, you still have 990 left to fly!" And then we have to invest our own money to modify and upgrade them. Because we respect the money of our fellow citizens. That’s taxpayer money. That’s people helping us. Volunteers. When you see my grandmother chipping in 100 hryvnias from her pension every time, to support the Hornets… And people keep donating, supporting us. We value and respect that. That’s why we put in as much of our own money as we can — just to keep everything working.

- And instead of sending that money to the families, a pittance, for which people at the market look at you with hungry eyes

Exactly. But it should be like this: the manufacturer is assigned to several brigades. And the end user clearly states: this is the product, this is what I need you to make. They give him the tech specs. He delivers and that’s it! Job done and much faster, too. If things worked that way, I think it would be much easier for the manufacturer than just handing out junk.

And then we still have that old Soviet narrative: everyone wants to have their own stash. So the command and others have hoarded themselves a bunch of FPVs, you know, just in case.

- Like canned goods?

"Exactly. I’ve seen cases where they just wasted the money. They stored those FPVs improperly — they’re unbalanced. You might as well throw them out, they’re relics now, can’t even fly anymore. Look, I get it — everyone wants to have some kind of reserve; that’s normal and reasonable. But not in this case, because you have to understand what you’re storing! An assault rifle, sure, it doesn’t change. A 120mm mortar round it’s still usable; you store it. But drones don’t work that way! And when we get drones from a certain manufacturer, and the guy shows up, we tell him: this is junk, throw it away. And he goes, ‘But guys, we made these two years ago, where the hell did you even get them?’"

IN POKROVSK, THE ENEMY IS DROPPING 20 TO 30 GABS ON US EVERY DAY. AND WE CAN’T EXTEND OUR RANGE BECAUSE WE STILL NEED TO REACH THE ENEMY OURSELVES.

- Our conversation so far is turning out to be rather critically grim. So, camera systems are often subpar. You’ve got issues with fiber optics. Drones are arriving expired. Can you at least tell me that you’re doing fine when it comes to ammunition?

- It's a bit complicated. Of course, when a soldier is motivated, nothing ever feels like enough; there’s always a shortage, he wants to be as effective as possible. So don’t get the impression everything’s doom and gloom. We’re still working, and we’ll keep working, taking out the enemy. As for ammunition, well, sometimes we do have to wait a little longer than we’d like…

- Why is that? There are lots of manufacturers now. And they compete with each other. Their Telegram channels are full of flashy videos — dropping payloads into an APC hatch or taking out another orc.

- Making a flashy video, that’s not the hard part. But making a quality product... In our battalion, we’ve got seasoned combat engineers. As they say, ‘Where you studied, I used to teach.’ That’s the level my sappers are at. They’ve been through it all since 2014. So someone brings in nice-looking packaging and says: here, take it, test it. They just glance at it, run the tests, check how it detonates, what kind of brisance the explosive has. And they go: this is crap…

You can make any picture you want. I had a pilot once, he dropped a grenade right into the hatch of a tank, and it blew up. A grenade! That’s basically impossible. I mean, you throw a grenade at a tank, it doesn’t care. It’s like tossing a pebble at an elephant. But sometimes, you drop a TM mine, and it just so happens the enemy had a whole nuclear-level stockpile of TMs and ammo there. So you hit it with a 500-gram charge dropped from a Mavic and boom, it’s like a nuclear blast! The picture is perfect! (Ironically) And we’re like: "Check out the kind of explosions we’re pulling off with this little payload!"

- Tough question: what’s the main cause of casualties and injuries among your troops? Drones, artillery, mortar fire?

- In Pokrovsk, GABs are doing massive damage. We’re holding a small section of the front and we can’t extend our range, because we still have to reach the enemy ourselves. So we’re limited in distance. And the enemy is dropping 20 to 30 GABs on us every day. They’re flattening our shelters, breaking them apart, taking down nine-story buildings. Right now, they’re hitting so hard that Pokrovsk is being leveled. We’re already running out of cover options. What we have left, it’s not great… we don’t have much variety to choose from.

FPV drones are also deadly, they knock out a lot of equipment. God protects our unit, our losses are minimal. But there are still cases like when Saba was killed. A Hero of Ukraine, now posthumously... He was a well-known guy who truly earned that title. And many of our guys have surpassed a thousand confirmed enemy kills (as a personal achievement). These are Men with a capital M. And not just the ones pulling the trigger, everyone who contributes. That’s when the entire unit works like a single machine.

- Given how inaccurate GABs are and how many the Russians still have, it seems like they’re just carpet-bombing you with them."

- Things have changed a bit. GABs used to be wildly inaccurate. But now the enemy is upgrading them, and they’re hitting with pretty decent precision sometimes. The problem is, where they hit, there are civilians. But they don’t care. Pokrovsk is already filled with civilian graves. They bury people right in the courtyards. There are children’s playgrounds there, now they’re covered in graves. So those who remain, they’re just getting ground down.

- And the people who are still staying in Pokrovsk, are they ‘awaiters’ or more of the ‘I’d rather die here than leave my home’ type?

Mostly the latter. Back when we were closer to Avdiivka, I did run into a few awaiters. But now, it’s mostly people who’ve simply chosen to stay.

- They said it straight out?

- More or less. It was obvious. You didn’t need to press them — it showed. But here, things are a bit different. One old man even recited patriotic Ukrainian poems to us and told us how much he hates the ‘ruskies’, called them all f*ggots and the like. And a lot of civilians say they’re fed up with the constant shelling and the destruction of their city and homes. So I’d say most of them lean more toward being patriots — people who really hate the Russians but just can’t bring themselves to leave their homes. I spoke with one woman, she told me her neighbor, Halya, went deeper into Ukraine. Stayed there for two months, they gave her a dorm room. And then they told her, ‘Well, now you’re on your own, figure it out.’ So Halia came back. Said, ‘We’re not wanted there either.’ I don’t know how true that is, but still…

- Honestly, if you put yourself in these people’s shoes, it’s horrifying.

- Exactly. Everything you’ve worked for your whole life, everything you’ve built, you have to leave it behind, grab one bag, and head off to God knows where, with no real support. And that’s exactly where the support should be going, to these people. Because, say, one person leaves and spreads the word, says, ‘It’s actually great here.’ And then more people would follow, I think…

- Viacheslav, am I right in understanding that this war places special emphasis on taking out enemy UAV units? And that for your troops and officers, there’s a kind of special thrill in this hunt?

- Absolutely. Drone operators have always been worth their weight in gold. We’ve heard it ourselves, over intercepted comms, for example. They’d lose it when they realized we were nearby. The second they spotted us, they’d start hammering our position…

- Same on your side?

- We try to do the same, as much as we can. For us, eliminating those so-called colleagues is critical because it’s one of the most effective things we can do. There was this one time, between Novohrodivka and Selydivka, a tiny village called Marynivka. Just one street, a handful of houses. But it’s on high ground and exposed terrain. And together with the brigade’s infantry, we wiped out about 500 enemy troops there in a week. It was pure carnage. Enemy meat, plain and simple. And after that, they started hitting us hard in return.

- So, when either side takes out enemy drone crews, it’s basically a celebration?

- No doubt. It’s a priority. I believe it’s one of the most important priorities we have.

- Do you have any predictions about what changes we might see on the drone battlefield by the end of this year, in terms of technology and tactics?

- Yes… though it's hard to predict. I believe fiber-optic systems will reach a whole new level. And I hope that worthy people will be at the forefront of this progress here in Ukraine. Because this is a new frontier. Unfortunately, many of our official regulations don’t even mention UAVs, not even close. We need to revise our military statutes, reassess what VOP and ROP mean, rethink engagement ranges, all based on modern warfare, not some outdated Soviet manual that still defines distance limits. We need to put people in charge who have already proven themselves. Not just keep them in their units. And yes, it’s tough — pulling someone out of a frontline unit and putting them in a leadership role. But people like Magyar, Veres, Achilles, their units should be the driving force behind this development. And we need room to grow, too. We’ve got tons of ideas for how to use different types of drones. And we have the people to make it happen. But we need more of them. And we need them now.

- Right now we’re speaking in Kyiv. Many soldiers coming from the frontlines are irritated by the number of police officers and their fancy vehicles on the streets. Do you feel the same?

- About the cars, yeah. We’re driving stuff that’s barely holding together. We had one new vehicle, fresh from the dealership. But now the clutch is shot, and everything else is falling apart too. That’s what happens when you drive like we do, with that kind of intensity and speed. We’ve basically got a whole repair shop out there. And then you see a shiny new pickup cruising down Khreshchatyk. And I’m thinking: what the hell does he need that for here?

- One police officer, a decent guy, honestly, told me when soldiers complain about their cars: ‘If we gave them my vehicle, they’d wreck it in a month! And besides, it’s about status, and law enforcement’s still needed in big cities.

- We could give them a vehicle that works just fine for city driving. Good off-road capability too. It’s not about status, we’ve got purpose-built vehicles. What we really need are pickups that you can load up fast. This isn’t about throwing a bunch of rags in the trunk. We’ve got masts, generators, Starlinks, tons of gear. We can’t even use a basic jeep…

- So you treat vehicles with respect. No wonder transport always shows up on your list of satisfying enemy targets, right alongside their personnel and hardware.

- We’ve absolutely wrecked their logistics in the past few months. We’d be sitting in place, and they’d roll out from Selydove toward Dniprovska. Oh man, we lit up their convoys with drones... Counted 40 vehicles torched and scattered, there was barely anything left to recover.

It’s basically a vehicle graveyard out there. Soon they won’t even be able to drive through. They just drag the wrecks off to the roadside. Because of that, they’re now driving around in old Moskviches, some beat-up vintage Bobiks. Those old UAZ vans… but the Bukhankas — that’s their classic. But when I see a Moskvich, I’m genuinely surprised. Zhigulis, Nivas with the roofs chopped off…

"THERE ARE NO BAD SOLDIERS — ONLY BAD COMMANDERS. EVERY PERSON HAS THEIR STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES. THE KEY IS TO FOCUS ON THE STRENGTHS AND DEVELOP THE WEAKNESSES."

- As far as I know, you’re originally from Zhytomyr and began your service in a Volunteer Formation of the Territorial Community (VFTG). Then you joined the Zhytomyr TDF, and in December 2023, you became part of the Oleksa Dovbush Brigade. What was your commander thinking when he appointed you first as a company commander, and now as the head of a battalion of unmanned systems? What did he see in you, considering you didn’t have prior experience leading a UAV unit?

- Maybe I’ll sound a bit harsh — and not exactly nice. But it’s the truth. I’m an honest person, and I try to stay that way. In war, when it comes to personnel, you don’t always get to choose. You’ve got a bunch of civilians and not a single career military person, especially in a new field like this. And some people don’t want to learn, and they don’t know how to treat others properly. They end up turning the whole unit against them. So you have to make staffing decisions blindly, by trial and error.

- You need to listen to others and find common ground. And you have to use people’s strengths.

- Exactly. In our unit, all decisions are made collectively. We’ve got a sergeants’ council — kind of like a Cossack council. We sit down, talk everything through, and vote on it. Sure, I have the final say as the commander, but I listen to everyone. My guys often come up with ideas themselves, like, ‘Hey, let’s try this.’ We weigh all the options, then pick one, test it, and execute. But a foolish commander just says, ‘This is what I’ve decided, do it,’ and that’s it. And when it doesn’t work, he turns around and says, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t execute it properly.’ Then he circles back to what someone else suggested in the first place…

I take a different approach. I’ve been right there with them, digging positions, coming under fire, evacuating the wounded. I always tell them: my life is no more valuable than any of theirs.

- It’s clear that in the battalion you’re, first and foremost, a manager. But what about technical knowledge and skills? In your position, do you need to be a specialist in everything, a technician, a tablet operator, a drone pilot? Or is that unnecessary, because then you’d stop doing what matters most as a battalion commander?

- The main thing is trust within the unit. When your people trust you, and you trust them. I always tell them: the most important thing is to tell the truth. I might not understand everything. But I know they won’t make excuses, they’ll tell me the truth.

Trust and honesty between the commander and the troops, that’s what matters most. As for the technical stuff… they’ll explain what I don’t know. One of them tells me: this is how it works. And I believe him because I trust my specialists. They’ve never let me down.

- And what if someone fails that test, not once, but two or three times? Would you try to get rid of them?

- No. Back in military academy, I had some pretty decent instructors. One of them used to say: ‘There are no bad soldiers, only bad commanders.’ Every person has strengths and weaknesses. You have to focus on their strengths and work on improving the weak spots. Give them a chance. You’ve got to find the right approach. If you just say ‘goodbye’ after one mistake, it doesn’t work that way. People aren’t lining up to join the army like they did in 2022. Right now, we’re critically short on manpower. And if you start wasting people and saying ‘get the f*ck out,’ soon you’ll have no one left. They’ll all run from you.

- What does a typical day for a battalion commander look like? What time do you get up, what’s your routine?

- It depends. Sometimes you don’t sleep at all, when things get critical. The days blur together, totally random. But usually, if everything’s calm, you wake up and go for a walk with Shershen. That’s our spirit animal, a corgi. Very calm, well-behaved. Sure, he flinches a bit every time something hits nearby, but he’s fine...

– So, you went out with Shershen. What happened next?

- Lately, I’ve been working on my physical shape. Makes a big difference, you just feel better. I try to alternate: one day it’s strength training, next day — running.

- On average, how much sleep do you get?

– When the crews head out for briefing, I sometimes don’t get back until midnight and by five you’re already up for the morning report. And then your phone starts buzzing… There’s a lot going on: calls, reports, you spend your evening analyzing ops, going through different group chats to see who did what, where there was activity. You check interceptions, other bits of intel. You piece it all together, down some coffee, go for a quick run. That’s how the day starts. Then I head to my command post, talk to the rear units about what got done yesterday. Just a casual talk, no stiff military formalities. We dress like civilians, no pressure. We go over the plan. They throw in their suggestions. If needed, I highlight what’s important. Or I reshuffle the tasks. The pilots — now those guys are super autonomous. You don’t have to babysit them or pull their pants up. No need to hand them a drone, they already know what they need. All you gotta do is occasionally throw a mission their way. They know the job inside out, where to fly, where the frontlines are, what needs spotting.

It all works like a machine. Sometimes I’ll say, "Hey, we’ve got some interesting intel over there, take a closer look." They do, collect the info. We get him ready with the Vampire, the night one. He shows up, boom-boom. Then a couple of FPVs follow and we just smash the position in broad daylight.

Sometimes we concentrate on a specific task. But usually, it’s routine. The enemy moves — we launch, wipe them out, that’s it.

"WE NEED TO RECRUIT MORE PEOPLE. AND WE’RE INTERESTED IN ANYONE WHO’S SIMPLY WILLING TO WORK…"

- How are vacations handled? Do caring commanders try to let their troops rest, even if it’s not always strictly by the book, but if the situation allows, send them home?

- We’re actually great on that front. Both the previous commander and the current one have given me real authority to make decisions. They don’t interfere with what, where, and how. The current commander always asks me with understanding about any issues in the unit. Any critical or urgent needs of the guys get addressed quickly. The commander never says no.

- That’s awesome. What’s the average age of your pilots?

- Around 30 years old. We don’t have a strict age limit. Though generally, the younger the pilot, the better, they’re more up to date with the tech. But we also have pilots in their 50s who work and are motivated. The only problem is health. You need to be fit for this.

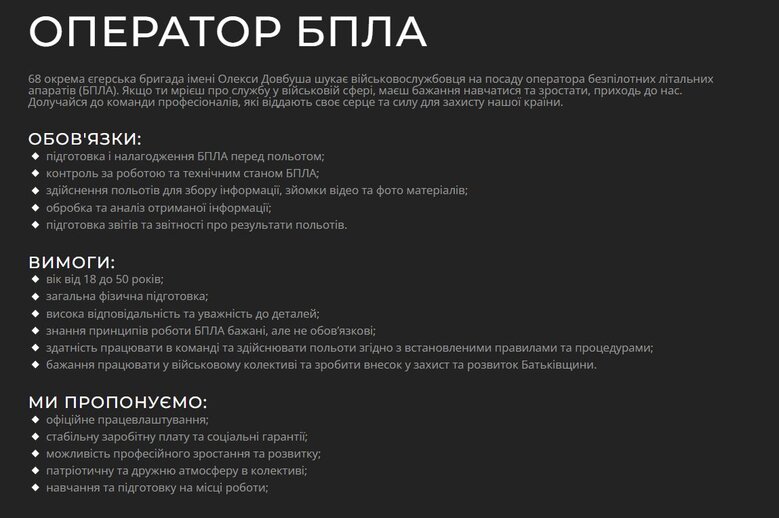

- You mentioned you need personnel reinforcements. Which positions are most critically understaffed?

- Of course, those who want to fly (and those willing to learn) are our top priority. But since we’ve tripled the size of our company because we’re moving to a corps-level system, we need to recruit more personnel. And here, we’re interested in anyone who simply wants to work…

WE WANT EVERY PERSON TO CHOOSE WHAT THEY WANT (AND ARE ABLE) TO DO IN THIS WAR. IF YOU WANT TO WORK A LITTLE FURTHER BACK, YOU CAN TRY FURTHER BACK; IF YOU WANT A LITTLE CLOSER, YOU CAN TRY CLOSER.

- I recently spoke with the chief of the medical service in the newly re-formed army-corps-level 3rd Assault Brigade. Their manning is tripling as well. In her view, the ideal breakdown is fifty percent core specialists, medics, and fifty percent support staff, who are just as important. Are you thinking along the same lines?

- Absolutely. We have billets for cooks, fuel handlers, mechanics. If someone isn’t in peak health but still wants to contribute, they can easily join Dovbush’s Hornets. Come in and say, "I can handle this job; let me get used to the war and to the operational tempo." Where we’re based, the zero line is relatively far off, no direct combat where we live. So you can take a cook’s slot, a refueler’s slot, and keep the unit supplied.

- So, all the vacancies on the brigade's website are also relevant to the Dovbush Hornets battalion?

- And more than that. Everyone can figure out where they fit and how to apply themselves. Take this example: a man came to us from the Territorial Center of Recruitment and Social Support (TCR and SS). He spent some time in the relative rear, filling out paperwork, processing write-off documents, which is also crucial. Then he said, ‘I want to move to combat duties. Nothing that scary about combat here; it isn’t infantry life in a trench.

So our aim is for every person to choose what they want (and are able) to do in this war. If you want to start a bit further back, you can do that. If you later decide to get a little closer, you can try that too. Every job matters, as long as you’re working. But in the rear, you have to work hard so the pilot is fully supplied and can get some rest. That’s the only way it works. If you’re willing to work, you can always find your niche, so long as you’re maximally productive where you are.

- A question from those thinking about a UAV-pilot career: Is it true that a pilot’s vestibular system needs to be in top shape?

- If you’re flying FPVs, yes, you have to get used to it. With a Mavic, the vestibular part is easier. You can orient yourself more easily. Some people don’t even know their own internal strengths, like whether they have a photographic memory or how well they navigate terrain. In flight, you’re seeing everything from above. Sometimes the link cuts out, you reconnect somewhere unfamiliar, then you have to orient yourself: where are you, what’s around you, and how do you bring the drone back?

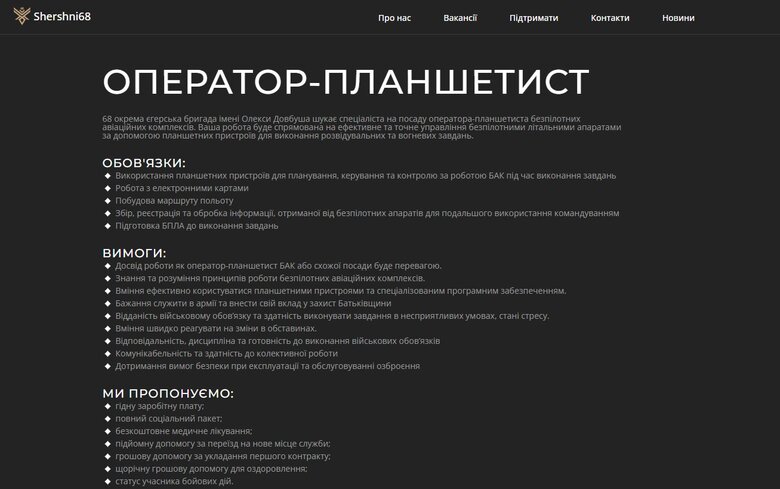

- Let’s circle back to the core vacancies. There are three: tablet operator, FPV-drone technician, and UAV pilot. The FPV tech is clear enough, the person who services and repairs the drones. But what exactly does a tablet operator do? What skills are required?

- It has to be someone who’s comfortable with gadgets and can keep situational awareness. Basically, he’s the navigator on the side. The drone pilot flies the mission, while the tablet operator watches the feed, tracks the flight, marks and calls out targets, monitors everything, and corrects as needed. And that’s not all. A tablet operator has plenty of other chores: refueling the generator, lowering the mast, swapping cables, repositioning antennas. It’s not just ‘I grabbed a tablet and never let go.’

- So a good battalion fighter is a jack-of-all-trades who can do it all.

- Exactly. Although I wouldn’t say all my top pilots can take apart and fix the gear themselves. That’s what specialized workshops are for. I don’t personally know how to disassemble a Mavic. But there are specialists for that.

- Where do your UAV operators work from? Tell potential recruits what to expect.

- We try to operate from the most fortified, 100% camouflaged positions. The days are gone when guys flew Mavics out of fields, controller in hand, with the b*stards just 500 meters away — tanks rolling up, armor closing in, and you’re launching a drone by hand. No trench, no dugout, nothing — just behind some trees. You get hit. You drop and stay down so you don’t lose the drone and controller together...

- Pilots are protected better now.

- Not that they weren’t back then. That’s just how it was — that’s how they worked. There weren’t enough losses to force a change. But now, you can’t just stand out there like that. Everything has to be concealed; antennas run separately. You sit in a proper shelter with your controller. Some pilots even operate drones remotely over the Internet from anywhere...

- In war, some jobs are ‘outsiders among their own.’ Snipers admit they’re disliked by other units because when a sniper hunts, the sniper gets hunted too, putting everyone around them in danger.

Can that analogy apply to UAV pilots? They hunt, and they’re hunted.

- That aspect is well understood and discussed with other commanders. We’ve agreed on the distance that must be kept between us and other units.

- That’s fair. On one hand, the analogy holds some truth. But on the other hand — where would you guys be without your UAVs?

- You know, the same goes for mortar crews. We hate the mortar guy standing nearby just as much. How does he operate? Using enemy coordinates — and you get counter-battery fire from him. Sure, it’s not super precise, but it lands somewhere near you, zeroing in. Not very pleasant, you know? It’s just as uncomfortable as a drone if it has a clear takeoff and landing zone. And if the drone operators are careless and not very smart, don’t follow camouflage rules, have their Starlink sitting out in the open, a perfect landing pad, antennas spread out in the yard, masts raised high… Any unit nearby would say to them, ‘Come on, guys, what are you doing?’

- Your brigade’s official slogan is ‘Your souls for our grievances.’ How do you personally interpret it?

- I see it as this: we take the lives of the enemy for our civilians, for our brothers. Our losses — to us, that’s a loss of family, a loss of kin. Because our unit has been built over a long time. It’s a family. It’s more than just a comrade in arms. It’s a battle brother. There’s nothing more precious. When you lose that, you have nothing left but a thirst for revenge. And that thirst — that motto reflects it. We are ready to take every enemy soul for the immense suffering they’ve caused us.

Not to mention the shelling of civilians because your heart bleeds when you see playgrounds destroyed by these bastards.

- How do you react to all these talks about ceasefires and the failed negotiations: Istanbul-1, Istanbul-2…

- I look at how brilliantly the bastard Putin is playing this, and Trump too, to some extent. Especially Putin. He’s playing on people’s despair. He’s playing on us. Those IPSOs (information and psychological operations) make both civilians and the military relax. Well, it doesn’t affect us that much — we see the situation on the front. The military isn’t that demotivated. But civilians — and then, down the chain, the military — are seriously demoralized. Putin is literally breaking our people from within. A typical example: I work with volunteers and say, ‘I need to buy this and that, can you get it?’ They say, ‘It’s tough now.’ ‘Why?’ ‘People think: peace is coming tomorrow, why donate, why work?’

- Yes, one can only imagine how these completely false hopes turn into disillusionment within the military.

- We can hope for anything, but as soldiers, we have to plan for the worst-case scenario. Prepare for the worst. There will be no ceasefire, not even close. All civilians must understand that the enemy won’t stop under any circumstances. Even if active fighting pauses, the enemy will continue working on their military industry. Our children will be fighting tomorrow. This is endless.

There are two ways we can react. Like with a house: you have a house or apartment, a thief comes and says, ‘This is my part of the house.’ You say, ‘Fine, live here.’ That’s the first option. Or, thanks to our resistance, the whole civilized world will understand that if you come onto someone else’s property, you must be held accountable. You will be punished. And this isn’t just about Russia. It applies equally to other aggressive countries.

- Finally, with what feelings and professional interest did Dovbush’s Hornets watch the high-profile SSU operation to destroy Russian strategic aviation? After all, drones were at the heart of the event. Pilots and tablet operators just like yours controlled them remotely...

- It was a major operation. They prepared for a long time. Glory to the execution and to the Defense Forces, and everyone involved. It’s very important that we show there’s no one to fear.

Am I right in understanding that a trick with trucks like that happens once? Now you’ll have to carefully design another combination.

- There are no limits with unmanned systems. It’s a flight of fantasy that’s not constrained by anything. New people with new ideas come in, and they rely on cutting-edge technology...

Attention! Those willing to support "Dovbush’s Hornets" can donate here:

Yevhen Kuzmenko, Censor.NET

Photos and video by the author + from the archive of the Dovbush Hornets