"Fact that veteran asks to turn down volume of music in car or in restaurant does not mean that he is making complaint. It may simply be causing him pain," veteran Ruslan Pelekhatyi

Before the full-scale war, Ruslan Pelekhatyi served in the police, and when the assault brigade "Liut" was formed, he went to the front as an infantryman-assault soldier. Talking about this period, he says that it was a conscious decision. As was his subsequent decision to return to work in the police, but in a civilian position dealing with veterans’ policy issues.

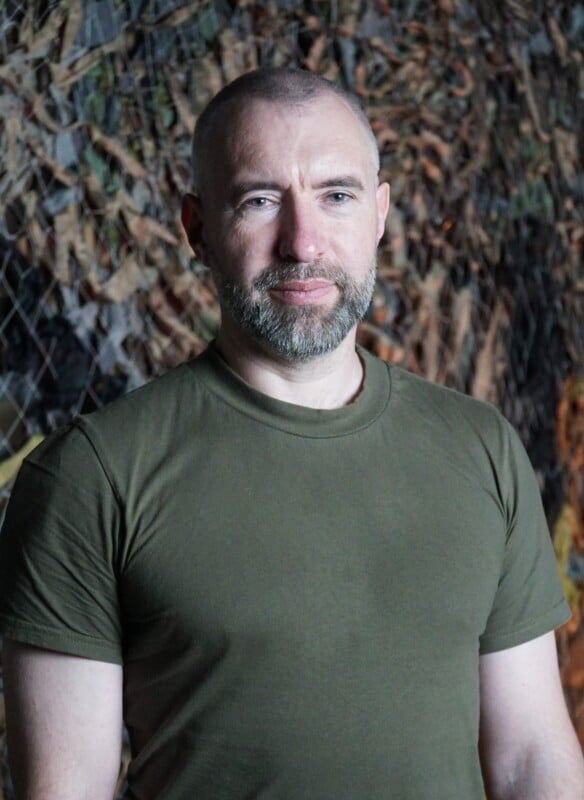

Since Ruslan was seriously injured during the fighting, we talked not only about the events at the front, but also about life after it. In an interview with "Censor.NET", the leading consultant of the Main Department of the National Police in Ternopil Oblast on veterans' issues told how to find a job for people who have been disabled as a result of combat injuries, what civilians should take into account in order not to create conflict situations in dealing with veterans, and how to return to "uniformed service" for those who want to continue serving after returning from the front.

"AT THE TRAINING GROUND IN THE 'LIUT' BRIGADE, I REALISED THAT I HAD TO LEARN FROM A SCRATCH"

- Mr Ruslan, police officers are often reproached that they should fight because they know how to handle weapons. How difficult was it for you to learn how to fight, even with such skills?

-I've said publicly many times that police officers deal with weapons, but the weapons they work with are not suitable for war. Police officers are taught to shoot short-barreled weapons - pistols. These skills were absolutely useless to me in combat.

In addition, not all police officers have good physical training; it is mainly those who serve in special units who do. If, for example, police officers work in pre-trial investigation or investigation, in the headquarters or analytical units, it is mostly desk work. Before I was transferred to the "Liut" assault brigade, I worked in the regional office in the department for organising the activities of patrol police response teams. My main job was to analyse and control the work of police patrol teams. In fact, it is a desk-based sedentary job. And although I kept fit, I wouldn't say it was perfect.

Of course, in order to join the police, citizens must pass physical fitness standards. This helps to weed out people who are not suited to the workload required by police service. Police officers also take annual physical fitness tests. But they are not difficult, 60% of civilians can pass them.

And when we started training at the training ground in the "Liut" brigade, I realised that I had to learn from a scratch. Work with automatic weapons and heavy weapons, combat tactics. Even basic military grenade throwing. We police officers were not taught this.

A policeman has a level of knowledge and self-discipline, he understands the military hierarchy and how this system works. Because the police and the army are somewhat similar.

We are used to following orders and regulations. It's easier for us than for civilians. But if a police officer joins a combat brigade or starts training as part of a rifle battalion, he or she has to learn almost from a scratch, as I said.

- Were you trained for assault operations in "Liut"?

- Yes, 'Liut' is an assault brigade.

- I heard from other police officers that it was difficult to recruit people when the brigade was being formed. They were afraid, they said that becoming an assault officer was like choosing a one-way road. Did you join voluntarily or under orders?

- No one forced me, it was my conscious choice. At first, it surprised my colleagues a little bit, because I hadn't told them about this decision beforehand.

- Why did you join? What motivated you?

- My choice was mainly due to the fact that a lot of friends, acquaintances, former colleagues from the militia who retired joined the Defence Forces after the start of russia's full-scale invasion. And I joined the "Liut" Brigade in 2023, when it was created. At that time, many of my police colleagues have already been at the front. I also wanted to defend the country in combat, so I made this decision.

- Is there any difference in the training of infantrymen who participate in assault operations?

- This question can be answered more clearly by the instructors who conduct the training. From my experience, I can say that any assault can turn into a total defensive position at any time. And vice versa - if the guys see that there is an opportunity to "push through" the enemy defence, they will go for an assault, even though they themselves have been holding the line.

The training is most likely common to all infantry units. Because infantrymen are universal fighters. We carried out both assault operations and defended the taken positions.

- You have been fighting in the Bakhmut sector when you were wounded. Was it the battle for Klishchiivka?

- At that time, the Third Assault Brigade was fighting for Andriivka, and our units, together with the Ukrainian Armed Forces, joined the fight to retake Klishchiivka from the enemy. But our main task was Kurdiumivka. Our main forces were involved there. It was a protracted battle. During the time the Russians had been in this village, they had the opportunity to dig in well enough and reinforce themselves. It was very difficult to knock them out of their positions. Especially for our police unit without much experience in combat.

- Were there still locals there at that time, or had they all left?

- As far as I know, there were no locals left. Because these villages were completely in ruins, the Russians "demolish" everything in their path.

- Nowadays, people mostly say that the current war is a war of drones. Weren't there so many of them back then?

- At that time, drones have already been more active in our and other areas. In particular, in Zaporizhzhia direction. I had heard about it from my brothers-in-arms. At the end of September, the first fpv drones began to appear in our area. But the enemy was working with "Mavics" quite actively both day and night. Drops, adjustments of mortars.

Drone warfare is, of course, good. But the final "clearing" of positions and their occupation is still the work of assault units in the near future.

- You mean we need people?

- Yes, we do. As fpv drones and other unmanned aerial vehicles become more widespread, it is becoming harder and harder for people, especially infantrymen and assault troops, to work. Now, due to the activity of enemy drones and ours, assault operations, both on our side and on the enemy's side, are an extremely high risk. And we can all see how the enemy operates. They are not very interested in personnel. Their main task is to accumulate and advance in a certain direction. They are not interested in the cost of doing so. They take in quantity, in manpower.

- How valuable were people to your commanders? When the brigade was being formed, some police officers who did not want to go to the front said that no one would worry about the personnel, the main thing was to report that they had formed the brigade.

- Planning military operations is similar to playing chess. No one can predict with 100% certainty what move the opponent will make. Therefore, operational planning is necessary, and work is underway on this. But no one can be 100% sure how the operation itself will go.

As for whether the soldiers were valued, I would say this: if there is no unit, there is no commander. Therefore, in our unit, the commanders were interested in bringing their men back alive. I'm speaking for those who went into battle with us - these are the squad leaders, platoon leaders, and the company commander who was directly in charge of the operation. They were fully cooperative and interested. I will say more. When I was wounded, the guys carried me out, so to speak, in their arms. The weather was unfavourable - rain, mud underfoot, there was no way to send transport because it could get stuck and this would have put people in even greater danger. And it was too far to carry me. So a group came to meet the group that was carrying me and help me. It included one of the battalion's deputy commanders. I think this says a lot.

The phrase: "Commanders do not value people" is like two sides of a coin. There were cases when the guys reproached that a car was not sent for them. And they had to be evacuated under fire, carried in people's arms. I witnessed an incident when the guys who were leaving in a vehicle were hit by an anti-tank grenade launcher. There were a lot of wounded, they asked the command for help, to send transport for them. The commanders listened to them, sent the vehicle, and thus the second vehicle that came for evacuation was also "blown up" by the ATGM.

That is, the commander must always soberly assess the real situation and the real possibilities for evacuating the personnel.

I had mixed feelings when they said that the car would not come for us. At first, I thought they didn't want to risk transport for me. But then, when the guys started carrying me out in their arms and I saw the state of the road, I realised that I probably wouldn't want the car to come to take me. Because vehicles are the first target on the battlefield. And maybe it would have been safer to evacuate me manually, despite the efforts the guys made and the risk they put themselves at. Because a mortar or other heavy weapon would most likely have started firing on the car. So, in such situations, there are really two sides of the coin.

- And how did you get injured?

- On the road where we were supposed to go, the Muscovites "scattered" mines - the so-called "petals". And on the way out of the position, I "found" one.

- Haven't you noticed it and stepped it on?

- It was about four o'clock in the morning. It was dark, cloudy, and raining. We could not see anything under our feet. We could barely make out the road we had to walk.

As I found out later, several other guys from other units also "found" these "petals".

- When you returned home, your colleagues did not tell you: "You see, you have lost your leg. Don't you regret joining? Did you really need it?". I'm sorry if I didn't phrase it correctly, but unfortunately, such situations do happen.

- I understand exactly what you are asking. But I was lucky. I returned to the same department where I had worked. And my colleagues, who knew me quite well before, were very understanding. There were no questions, like: "Ruslan, why have you done that?" They all know perfectly well that my decision was fully conscious. So they know what kind of person I am. So there were no stupid questions from anyone.

- Have you ever asked yourself this question? You know how it is when something happens and you start thinking, what if things had turned out differently?

- I know - this is the victim syndrome. When a person begins to wonder: what would have happened if I hadn't left. They blame themselves, saying, why did I do that, how will I live on ...

This kind of self-pity is not for me. It not only helps in later life, but also harms. When it became known that I would have to have my leg amputated, I realised that I needed to look for solutions on how to cope with this and what to do next. I "switched" to my new reality.

Now I have a prosthesis, it is quite well made. I had it fitted in Ukraine, in my native Ternopil. If there are any problems with the prosthesis, they are solved on the spot.

I work and live my life. I go in for sports, meet with colleagues and my comrades.

Everything is fine with me. The main thing is that you are alive, so you should not dwell on what had happened. If you got out of there, you were already lucky. And there is no point in feeling sorry for yourself, you have to move forward.

"WHEN I ARRIVED AT THE STABILISATION POINT IN DRUZHKIVKA, THE SURGEON IMMEDIATELY TOLD ME: "YOU WILL HAVE A PERFECT AMPUTATION".

- When did this realisation come?

- Immediately after I was wounded. I saw my leg and realised it was almost gone. When they put a tourniquet on it, I kept track of time. By the time we got to the hospital, I knew I would have to have an amputation.

- How long can the tourniquet be kept in place to avoid amputation?

- Ideally, 2-2.5 hours. If it's up to three hours, it's at the doctor's discretion. And the distance the guys carried me was about five kilometres. It was impossible to meet this time. And we were moving under mortar fire, mines arrived. They were hiding me and hiding themselves in certain areas. That's why the journey was quite long and difficult.

When I arrived at the stabilisation point in Druzhkivka, the surgeon immediately told me: "You will have a perfect amputation". Then I was injected with anaesthesia and I did not have time to ask him what "perfect" meant.

- Do you remember the first morning after the operation?

- I had already known that my leg was gone. I got up, looked, and made sure. Then the doctors did bandages, and then I was transported to a hospital in Dnipro. There I underwent an initial operation to suture the stump and five days later was transferred to the Ternopil Regional Clinical Hospital, where I underwent a number of other operations and had my leg fitted for a prosthesis.

- Have you found out what a "perfect amputation" is?

-Yes. My prosthetist said that if the leg was amputated a little higher, there would be a problem - the prosthesis would have nothing to fix on. If the amputation is low, i.e. a lot of the leg is left, then there can be problems with blood circulation in the limb, because it is clamped in the prosthesis and the lymph flow is disrupted.

I was lucky to have a fellow soldier who applied the tourniquet in the right place and in a reasonable manner. Because if they had put it on me as taught in civilian courses - as high as possible, I would not have had my leg completely.

There have been cases, especially at the beginning of hostilities, when in the confusion and panic, the tourniquet was placed as high as possible. Then they did not examine the wounded further. They brought him to a stabilisation point, and there it turned out that there was no massive bleeding at all. That is, a pressure bandage was enough. As a result of all this, there are cases of high amputation of the leg, which is very sad.

- Is the comrade who helped you a combat medic?

- No, he is also an assault man, but he has been fighting since 2014.

In addition, our combat medics were constantly conducting tactical medicine courses for us. Even when we have already been on a combat mission at our permanent deployment in Donetsk region. When we had time between combat missions, they gave us additional training. They wanted us to repeat things, learn something new, and practice our skills.

- How difficult was the rehabilitation course after your prosthesis? Because the guys told me different things. Some were lucky with rehabilitation therapists, and some met those who did not understand how to work with war injuries.

- I will not reveal some very terrible military secret if I say that we currently have a big problem with physiotherapists and rehabilitation specialists who know how to work with war injuries. Physiotherapists and rehabilitators working in clinics usually have experience working with patients who have undergone rehabilitation after domestic fractures or strokes. Not every physiotherapist and rehabilitation specialist in every medical facility knows how to work with military personnel who have amputations or a shattered leg after mine injuries, etc.

New departments are now being opened to provide relevant training. People have finally realised that we have an urgent need for such specialists. It would be good if there were permanent refresher courses or if they were sent abroad to specialised rehabilitation centres to gain experience working with the military.

I can say I was lucky. I got into the hands of qualified specialists at the prosthetic centre. They prepared me for the prosthesis and then spent another week teaching me how to use it. How to walk on different surfaces, how to go up and down the stairs.

During this process, the prosthetists adjusted the prosthesis itself. That is, everything was fine. But what do I want to say to my brothers- and sisters-in-arms? A lot depends on the wounded man himself. A physiotherapist or rehabilitator can teach basic skills. But the further process of rehabilitation and walking on the prosthesis itself depends on us.

I know that some of the guys, having received a prosthesis and walked on it for a while, throw it on a shelf or under the bed. Because it is uncomfortable, it presses into the leg, rubs, hurts. I compared this feeling to buying new shoes and trying to walk in them. At first, your foot will be getting used to it. Even if it is good and of high quality, there may still be some nuances somewhere. But the more you walk, the faster your foot gets used to the prosthesis. Eventually, they become one.

- How long did it take you to learn to walk?

- At first, I could walk about three hundred metres. Then my leg started to swell and I had to sit down, take off the prosthesis and rest a bit. Then I would put it back on and continue walking. It went on for several weeks. Then I set myself a goal - to get to the Ternopil lake on foot. It's about 650-750 metres away. And in five days I reached it. Then I set a goal to walk a kilometre every day. After 21 days, I left the rehabilitation centre without crutches and without a cane.

It was difficult, hard, my leg was hurting and swelling. I took off the prosthesis, rested and walked on. Because if you want to walk, you have to do it.

- How do you motivate yourself after such a severe injury to get up every day and do something? You have to do it through pain...

- I do not consider my injury to be severe. There are guys with much more serious injuries. We are now engaged in veteran adaptive sports with my fellow soldiers. I see guys playing table tennis without an arm. Guys without both legs playing sitting volleyball. Guys are lifting weights, working out on crossfit training machines.

Blind people also go to competitions all over Ukraine and play sports.

We have a guy with a double high amputation of the lower limbs working in the police. He comes to work, works his time in the team, and does not stay at home.

People are in society, they don't shut themselves away. That's why I try to convey the message to all the veterans I talk to: people, you can do it, the main thing is to want to. To close in on yourself, to stay at home with your problems, thinking how hard it is for you, is not an option. You need to get up and go. And if you want a door to be opened for you, you have to knock on it first.

- Didn't you have moments when you felt like freaking out?

- Yes, I did. Then the prosthesis was flying around the house. But then I jumped to it on one leg. Because I realised that without it, I was not mobile at all. So I picked it up, put it on and kept walking on it.

When it hurt so much that I couldn't walk anymore, I would take it off and let my leg rest. Then I would continue.

- When you returned home after rehabilitation, you were invited to work in the police again. Have you thought about any other employment options at the time?

- When I was called, I was still in rehabilitation. My former supervisor called me and said: "Ruslan, stop being treated, come back, there's a lot of work to do." We joked with him, talked and I decided to come back. He didn't give me time to think about it, and I didn't really think about it much. Even though I had had a lot of plans before, I decided that I would join the police as a civilian and would have more free time.

- So the position was different?

-Yes, the work was somewhat different, but the team was the same.

- When did you start working with veterans?

- Since March this year. The head of our main police department, Serhii Ziubanenko, called me and said: "Will you be my deputy for veterans?". I answered: "I will".

Perhaps I was motivated by the fact that many of my colleagues who were at the front called me to ask for advice, to ask how they should prepare their documents, whom they should contact to get a certificate or to clarify a law. I tried to help, and I read a lot of information about veterans for myself. So I have already been doing this work at my level. And this offer to help the guys at the official level, of course, interested me. I saw a chance to do something important for my brothers-in-arms, for the guys who are still fighting. Perhaps someone will perceive this as pompous phrases, but I believe that it is my duty to help as much as I can to the people who are now protecting me.

- Can those who have been injured and demobilised return to work in the police?

- Let me give you an example from my own experience. The military medical commission declared me unfit for further service in the police. Because the order they were guided by at the time I passed it was not adapted to those police officers who might be injured in the war. And I work in a civilian position.

This problem has now been resolved. The order has been amended to ease the requirements for medical indicators and physical condition of police officers who were injured during hostilities. This was done in order to keep them serving in the police. A division into categories of positions has been made. There are rear positions that require less physical activity. These are analytical work, personnel work, etc. For all these positions, we accept and are ready to continue accepting colleagues who have been injured at the frontline.

In addition, we are currently developing a mechanism for employing both military personnel and all members of the Defence Forces in the police with disabilities. And to certified police positions.

- That is, are we talking about the service in uniform?

- Yes. For active police officers, this opportunity already exists. For example, I can restore my rank and continue to serve in uniform.

- Are there enough positions for veterans?

- The biggest problem now is with veterans who have received a disability due to severe injuries. I'm trying to get them jobs not only in the MIA system. I have already established contact with the employment centre and am in contact with entrepreneurs. To find jobs for more people with disabilities. But there are certain difficulties. Because in such cases, employers need to expect more sick leave.

Employers are not always ready to work with veterans with disabilities. There are positions in the police, but the staff is also limited. We can hire a certain percentage of people with disabilities, but for positions that do not involve significant physical activity. Because we are still a power structure. And we mainly need people who are able to walk, run and perform official tasks.

Currently, about 10 people with disabilities are working for us. We are also employing people in our service centre.

In addition, the security police department is actively involved in hiring. By the way, there is a fairly large demand among veterans to work in security structures.

That is, I look for veterans who come to me to work in different areas and different structures, depending on their needs and physical capabilities.

- What exactly do veterans do in the security police, which involves rapid response and visits to facilities?

- There are various options. We have people with the second group of disability in our security police. We also employed a veteran with the first group of disability. He was a security guard for the premises. A video surveillance system was installed for him, so he could safely monitor the territory and the building while sitting in his office. And if necessary, he called the rapid response team.

But, as it turned out later, this man could not sit for long. So I don't know if he continues to work or if he quit.

- If a person is alone and has limited mobility due to an injury, is there any way to help them?

- The only possible way for this person to interact with society and government agencies is through a veteran support specialist. Because the functional responsibilities of such a specialist are to support and assist veterans.

- How can a veteran find one?

- Through a family doctor or a primary care doctor who is now operating in the communities. They can find a contact and get in touch with a veteran support officer and then use them to keep in touch with the outside world. For our part, we actively cooperate with veterans' support specialists. For example, support specialists, as a rule, are not provided with a car. But the community police officer has a car. And he works in the same community as the veteran support specialist. Therefore, if the specialist needs to send a veteran from a remote village to the district centre to apply for documents or social benefits, he or she turns to the police. The police officer of the community enters a formal assignment in his system, and together they take the veteran and provide him with the necessary assistance.

Or there may be another situation. There is a specialised vehicle that transports a veteran. But the person needs to be transferred from the train to this vehicle or from another mode of transport. Or they need to be picked up from their home, or helped to take them out if there is no ramp. In such situations, the accompanying specialist can also count on the help of the police. That is, they call the police, and the police come and help.

- Don't the police officers get annoyed? Because people are different.

- Yes, there are different people. Veterans of the Armed Forces sometimes have conflicts with police officers. But when a veteran realises that a police officer is coming to help him, this aggression either does not manifest itself or is not so pronounced. For our part, we conduct trainings with police officers to teach them how to communicate with veterans with disabilities, and with veterans in general. What to say, what is undesirable, how to start a conversation, how to communicate. We have psychologists, and we are constantly conducting training. We are now planning to conduct on-site practical trainings in district police departments to work out in practice possible conflicts and ways to smooth them out and resolve them.

We understand the challenges we are facing now and will face in the future. That is why we are preparing, working to improve our knowledge and professional level.

- What advice would you give to civilians about communicating with veterans in conflict situations? For example, a person who has suffered several contusions reacts to loud music. And the person who turned it on does not want to turn it off, does not understand the essence of the complaint. Or there was some other situation that caused the military or veteran to become aggressive. How to avoid escalating the conflict? Shouldn't there be trainings for civilians as well?

- It would be very good. Maybe someone could make a series of videos. Because situations can really be different. For example, as you said, there are people who have suffered from acubar injuries. They react painfully to loud sounds. And the fact that a veteran asks to turn down the volume of music in a car or in a restaurant does not mean that he is making a complaint. It may simply be causing him pain. Therefore, it is necessary to convey to society that this is not a whim of the veteran, but a physiological need. A person can show a certain degree of aggression, and he or she does not control it, it seems to him or her that everything is normal. But people who do not understand this can also respond with aggression. Which should not be done. Because this will pass in a few minutes for a veteran. And if there is aggression in return, it can provoke a conflict.

I personally had several unpleasant incidents. For example, I was standing in a bank queue. I'm wearing shorts and it's obvious that I have a prosthetic leg. And everyone starts offering me a seat or insisting that I go out of line.

Or, for example, the situation in transport. Sometimes my leg hurts and it's not comfortable for me to sit, so I stand. And when I am asked to sit down in an aggressive manner, it is a bit annoying.

If a veteran needs help, he usually says so. If I need to be let through in a queue, I will go to the window, show my ID, apologise to the people in front of me and use the opportunity as a veteran. When I feel comfortable and nothing disturbs me, I can stand in a queue or in public transport.

Some guys are triggered, they don't know how to react when strangers come up to them and start hugging and kissing them. It's very annoying when they offer money. I think it's tactless to do this in general. For example, I feel much more comfortable if a person who passes by and wants to express gratitude simply says "thank you". This is quite enough.

Tetiana Bodnia, "Censor.NET"