"It’s lie! No money is paid for downed planes" – Fara, air defense platoon commander of Rubizh Brigade

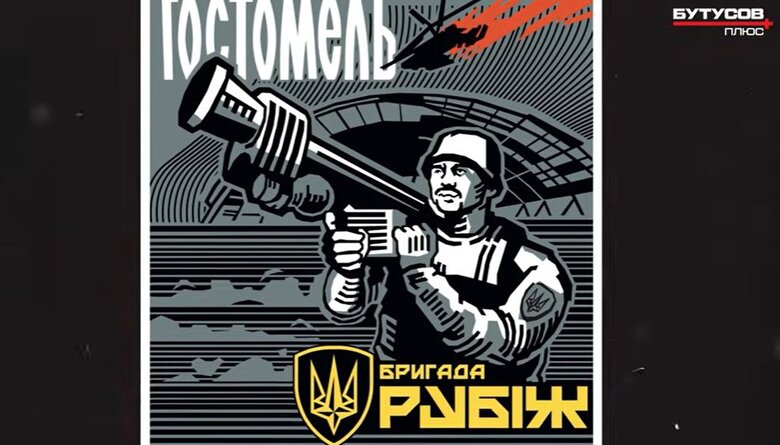

Ukrposhta issued a stamp in his honor — the legendary air defense platoon commander of the Rubizh Brigade was the first serviceman to personally take down two enemy helicopters over Hostomel in the opening minutes of the full-scale invasion, and later two Su-25 bombers near Bakhmut.

Serhii (Fara) Falatiuk, at the Hostomel airfield, showed the positions of his platoon and spoke about the first hours of the full-scale invasion — and how inexperienced air defense troops managed to shoot down enemy aircraft for the first time. He also talked about new developments, including anti-aircraft drones designed to help take down enemy reconnaissance UAVs.

"We were already on duty here. This was our post.

The guard post was behind that building. I was on guard duty at the time, there was one shift posted over there. Another group was stationed on the roof of the building.

The personnel were at their positions, and the ‘Varta’ armored vehicle was parked right here—under the bushes, more or less."

Journalist: Were you all sitting in the same vehicle?

Soldier: Yes, yes. We were sitting in the vehicle because, up until February 24, the management of Antonov State Enterprise (SE) had not provided us with any shelters or allowed us to dig in. There was a complete ban on fortifying positions on Antonov SE in order to avoid damaging the infrastructure.

There are a lot of underground power lines and cables beneath the surface.

On the evening of the 23rd, we were told that a large number of helicopters, specifically Ka-52s, had entered Belarusian airspace. I gathered my personnel, talked to them, told them Ka-52s had flown in. We opened Wikipedia and read about what kind of helicopters they were.

Journalist: And before February 24, you hadn’t fired a single shot?

Not with a live missile, no. We had only used mock-ups, standard military training simulators for the Igla MANPADS. We practiced only with the simulator. As for an operational missile, it was more like, opened the crate, looked inside: "Ohhh, that’s an operational missile."

Soldier: "There’s a pile of money just lying in that crate, you look at the missile and picture a Kyiv apartment." (LAUGHTS) "So I closed the crate, grabbed a mock-up, and went on across the range with the mock-up. That’s it."

"This barrel, it's full of fuel. Kind of a backup power station for the runway, emergency use. On February 24, we were sitting here, and I told the guys: ‘God forbid things go south, no one hides behind the barrel."Well, what I noticed on the 24th, no one did. Except me.

I was the only one sitting under it. Later, when aircraft started flying all over the place, I moved the ‘Varta’ armored vehicle behind the fence.

And that’s how we stayed on duty, until four in the morning."

Then, around 4 a.m., my shift was finally relieved. Some of the guys went up to the roof, others moved to a second position. They climbed up the fire escape behind the building.

And just as they reached the roof, I got into the Varta and shut the door, something fast flew over Kyiv and exploded.

We started checking the news, saw the President’s address, it was the start of the full-scale invasion.

I reported over the radio that I could hear a helicopter. The reply was something like: "There are no helicopters in the air. If you see anything, maintain visual contact."

From the direction of Belarus, through the tree line, I saw helicopters hopping over, one, two, three, four. I counted them.

Journalist: With binoculars or the naked eye?

Soldier: Naked eye — they were already too close.

Journalist: How did it happen that you saw them but they weren’t picked up?

Soldier: Because the radars we had in service back then were Soviet-era systems; that was no secret to anyone, including the Russians. They have the exact same sets. Everyone knew they detect everything flying above roughly 500 metres, but anything lower goes unnoticed.

It was a good thing they came in on Ka-52s: without hesitation, I shouted, "Fire on the enemy aircraft!" Had they been Mi-24s or Mi-8s, I’d have let them fly straight to the airfield.

The Ka-52 is in service only with Russia, so I let it come closer to check its recognition markings.

Roof of the building. Our position was here…

The roof here is white, this was February 24. There was no snow by then, so I asked my command to provide us with white ghillie suits because in black, a person was highly visible here. On February 24, the men stood guard on this roof wearing white ghillie suits. Everyone joked that we’d be wearing white ghillies in the summer.

I spotted the assault aviation Ka-52 coming from the tower side, command post area. I climbed down, grabbed missiles from the ground, and ran out onto the road to make the first launch.

I took a missile and ran onto the road. The Ka-52 was flying low right down the road toward me. I saw it coming clear and low (SMILES). I held the missile, stood my ground, watching it approach, knowing that according to all relevant regulations the minimum firing distance should be 500 meters or more. I realized it was too close for the missile to lock on properly and hit it. So I crouched down, and the big helicopter flew right over me. I turned and fired at it as it passed behind me.

In the back like a coward (LAUGHTS).

And then the thought hit me: why didn’t he fire at me? That was my very first question, why did he leave me alive? Why, what did I do wrong that he didn’t finish me off? Thank God he didn’t, of course, but that question still nags me to this day, why?

Journalist: He saw you...

Soldier: Yeah, I clearly saw his weapons, machine guns, even rockets. He didn’t need to waste rockets on me; machine guns, the cannon, it was enough to turn me into minced meat with just the press of a button or pedal. Maybe he thought I wasn’t shooting back, that I got scared and would run.

When he flew over me at about, I don’t know, 20 metres altitude

That cockpit is huge. I tried firing at him with my rifle, but it didn’t do anything. He flew right over me while I was hiding behind the barrel.

I made a second launch in the same direction. He flew off and struck the building where our personnel were stationed, then turned away.

From the same spot, I made another launch. That was the second Ka-52 that was forced to make an emergency landing, I hit him with a cluster of "Nurs" missiles.

Journalist: What’s your feeling here? This place, where you could have died, became the place of your glory.

Soldier: Me and my comrades, who were there that day, continue to defend our country. We talked about whether we’d want to relive that day. Probably not. No one wants to.

You understand you could have died.

That day, I had one dream, to survive the full-scale invasion, or at least get through that day.

Journalist: How many helicopters did your group shoot down in total that day?

Soldier: Six.

Journalist: And how many did you personally shoot down?

Soldier: Two.

They threw all their best forces in the first days of the war, after all, they were considered the world’s second strongest army. They wanted to unleash their full power in an instant, and that power completely crumbled in the second second of the war.

In the first second, they reached us; by the another second, they got their asses handed to them, that was it. They realized their power was collapsing.

Journalist: What was the situation around you like?

Soldier: Everyone was calling me then, "What’s the situation over there?" (SMILES) I said, "We’ve run out of missiles, we’re working with ZU-23-2s, so far no big results." Then the commander of the combined battalion-tactical group contacted me over the radio and said we were pulling back to secondary lines on the military base.

By then, Buryat troops had landed and were running through the bushes, so we started firing back a bit. We decided it was best to cross over via the armored vehicle to withdraw to our military base. Honestly, there wasn’t much fear then, it was all driven by adrenaline and excitement, because you’re out there fighting and everything’s burning.

I have a serviceman with the call sign "Truffle", he’s small, short. We’re still fighting together today. I managed to pick him up and toss him over a fence. We laughed about it later; I tried doing it again, but it didn’t work. At the time, fueled by adrenaline, I grabbed him in his body armor and all, just threw him over the fence and said, "Here, take the conscripts."

And that’s how the conscript service started.

Journalist: Which fence was it?

Here’s that fence.

There’s a ditch there. Behind that ditch is the retreat path to our military base. While we were withdrawing to the ditch, small arms fire opened up on us.

A helicopter was flying behind us. The helicopter was shooting at us. It was quite an exciting ride.

I was the first serviceman in the division to shoot down an aerial target. I was so pumped, I called everyone: the division commander, the battery commander, everyone, on the second or third day, telling them I’d downed a helicopter, saying, "I’m a hero!" (LAUGHTS)

The feeling was that the personnel were ready for the invasion; they were doing great, hitting targets. Their previous years of service hadn’t been wasted, they knew their equipment, they were worthy warriors of their country, destroying the enemy. Those machines the Russian Federation boasted about as "unstoppable tanks with rotors", they were falling and burning. The emotions were indescribable.

It just so happened that on the 24th I was there, doing everything I could to save the lives of my comrades and destroy as many aerial targets as possible.

We held back the enemy, gave our defense forces the chance to deploy combat formations on the outskirts of Hostomel, and prevented the enemy from advancing further. It might sound a bit grandiose, but in my opinion, we created a small yet very powerful shield defending our capital.

Bakhmut direction, October 2022

At that time, Bakhmut was still under full control of Ukrainian forces along with its outskirts. It was October, and fighting was ongoing around Bakhmut.

Our position was located between the settlements of Bakhmut, Kurdiumivka, Zelenopillia, and Ozarianivka, in the fields near a quarry.

Soldier: We moved onto the new defensive line at the settlement of Kurdiumivka.

We had just taken the position, I hadn’t even dropped my pack yet, when I saw an enemy Su-25 aircraft approaching. We identified it as hostile and launched a missile at it. The shot was successful; there’s confirmed evidence of a hit. Then we turned around and withdrew from the position. When you fire a missile, it creates a large smoke cloud and a significant heat signature, which puts the personnel launching it at risk, so it’s advisable to leave the position afterward.

Journalist: From what distance did you shoot it down?

Soldier: It was almost at the critical range, around 3 to 4 kilometers.

A helicopter is slower and less maneuverable, but a plane is a fast and agile target. That makes it difficult to lock onto, track, and hit.

It’s like firing a pistol, the bullet leaves the barrel and you can’t adjust its path; it goes where it goes. The same with a missile, it’s not like an anti-tank system like Stugna that can be guided slightly left, right, up, or down. Once the missile is launched, it’s committed. If the missile locks onto the target and the shooter does everything right, locks on, tracks, and launches, the missile will intercept the target and is on its way. Whether it hits or misses then depends entirely on the missile itself.

Journalist: Do you know what the task was?

Soldier: The missile struck the combat formations of our infantry or more precisely, an adjacent unit positioned to our left. The plane maneuvered and was already heading back to its base, the airport it came from, when we caught it on the retreat.

The second plane appeared around early October, about three to five days after the first, same direction but a different position. We took up position again, and in the afternoon we received a radio warning that enemy aviation would be operating in our sector. We went on alert, prepped the missiles, and waited. At first we heard the planes acoustically, then we spotted them visually.

There were two aircraft. We launched at one and confirmed a hit.

My partner shouted, "Hit again!" I said, "Yeah, understood—let’s get out of here."

They know we’re here, so they don’t fly this way, they know we’re not here, they’d fly here. But they did their job: shot down two, and that’s it. They don’t fly here anymore; they know it’s pointless. They have to fly somewhere else, where they won’t get shot down.

Journalist: Tell us about what you do now and how you requalified.

Soldier: With the decrease in large-scale enemy aviation activity, we started retraining specifically to counter FPV drones, tactical reconnaissance UAVs used by the Russian Federation, like Orlans, ZALA drones, and Supercams.

The division commander proposed creating a dedicated battery for this purpose and offered me command of it. I took command and formed the air defense battery focused on these systems. Now we fight as FPV drone operators against Russia’s strategic reconnaissance drones. This is also crucial during wartime because strategic reconnaissance causes significant harm to infantry, artillery, tank units, and all branches of the military, as well as to our entire defensive line. They fly high, have excellent visibility, and prevent logistics operations, for example, on position or ensuring safe operations for our artillery and movement for infantry on the front lines. When we cover their eyes a bit, it gives artillery and tanks a better chance to operate, allows logistics to run smoothly, and facilitates evacuation of the wounded.

Journalist: How do you see the war evolving with these innovations? Where are we headed?

Soldier: Yesterday, I was talking with a friend, and honestly, it’s a scary prospect where this is going. If it moves toward fully digital drone control, it’ll be a grim story. You could be sitting ten kilometers behind the front line, dropping nearly 120 mines from drones, that’s much more efficient and precise. Well, like I said, it’s a pretty sad story: when you’re positioned at long range, you’re protected, you don’t put yourself or your troops at risk, and you eliminate the enemy remotely.

Both we and the enemy can do this. So this isn’t just a sad story for Russia, but for both sides, because we both understand this and are developing capabilities in this direction, both of us very, very well.

Soldier: Our job is simple: for every shame they invent, whether to eliminate us or scout their forward edge, we have to come up with something better and kill whatever they’ve invented.

We fly in with FPV drones, shooting down their strategic reconnaissance drones. They’ve even mounted one of their strategic reconnaissance drones with an additional rear camera—like a car’s backup camera—because to destroy it, you need to catch it from behind. This camera lets them see what’s going on behind them, whether anyone’s approaching. If something comes close, they can maneuver and escape from us. So they’re already starting to fight back.

Interviewer: How many have you shot down?

Soldier: Since our battery was established, quite a few.

Around forty.

Interviewer: Over what time period?

Soldier: Roughly four months.

The challenge is the altitude, finding a target in the sky isn’t easy. The Russian Federation has begun painting its birds sky-blue so they blend with the sky, or black so they merge with ground folds, like their own kind of multicam.

Subjectively, flying low to take out infantry or hardware is much easier, because vehicles aren’t nearly as agile. We also initially thought the ZALA, Orlan, and all those Supercam drones had big wings, flew straight with preset parameters, and turned smoothly to fly back, but when we started engaging them, they turned out to be incredibly maneuverable. You approach within a meter, and it can suddenly drop like a hammer straight down. By the time you adjust your aim downward, it’s already sharply veered to the right and disappeared. And then you need about five minutes just to spot it again in the sky.

Because it’s thin and flat, I even think it’s easier to shoot down a helicopter than catch a ZALA. To shoot down a helicopter, you roughly need three servicemen, someone spotting, someone fixing the target on radar, and someone passing the info. But to take down an FPV drone requires a large team: someone to assemble it in the lab, set up solid communications, assign frequencies. Reconnaissance soldiers searching the skies, an engineer assembling the missile, a pilot flying, and a spotter guiding them, telling the pilot roughly where the target is. That’s up to ten servicemen working together to bring down one drone.

Interviewer: Have you received any awards?

Soldier: The Order of Courage, third class. No money is paid for downed planes. That’s a lie. Everyone asks how much they gave me, in every interview where I talk about it, the first comment is: "He must be a millionaire, two planes, two helicopters, that’s gotta make him rich, at least enough to pay off his loans."

Interviewer: Your image just appeared on a postage stamp. How does it feel... to be a stamp?

A postage stamp? A carrier pigeon? (smiles) When they called me and said I was getting a postage stamp made, it really lifts your morale, your patriotic spirit, though mine was already pretty high.

But still, it shows that if they made a stamp in my honor, it means I did something significant. I’m just an ordinary citizen of my country who, when the full-scale war started, took the right path, to defend my country, my family, my homeland.

Because just a couple of months before the invasion, my contract was supposed to end, and I planned to leave and find my place somewhere in civilian life. But as my wife told me, "You won’t be able to live without the army, and the army won’t be able without you. You won’t be able without your personnel."

I’ve been in the army since I was 18, I can’t do much else. Give me a hammer and a nail, I probably won’t even hammer it in. But give me any kind of weapon, and I’ll master it in five minutes.

No, well, I can hammer a nail into a wall (LAUGHTS). Basically, being in the army, at war, feels like being at home, I know everything here, I like this job. As long as the war goes on, I’m not thinking about going anywhere. Definitely no plans to swim across the Tysa River.