"Why did state deny me chance to live?" — story of military doctor with cancer

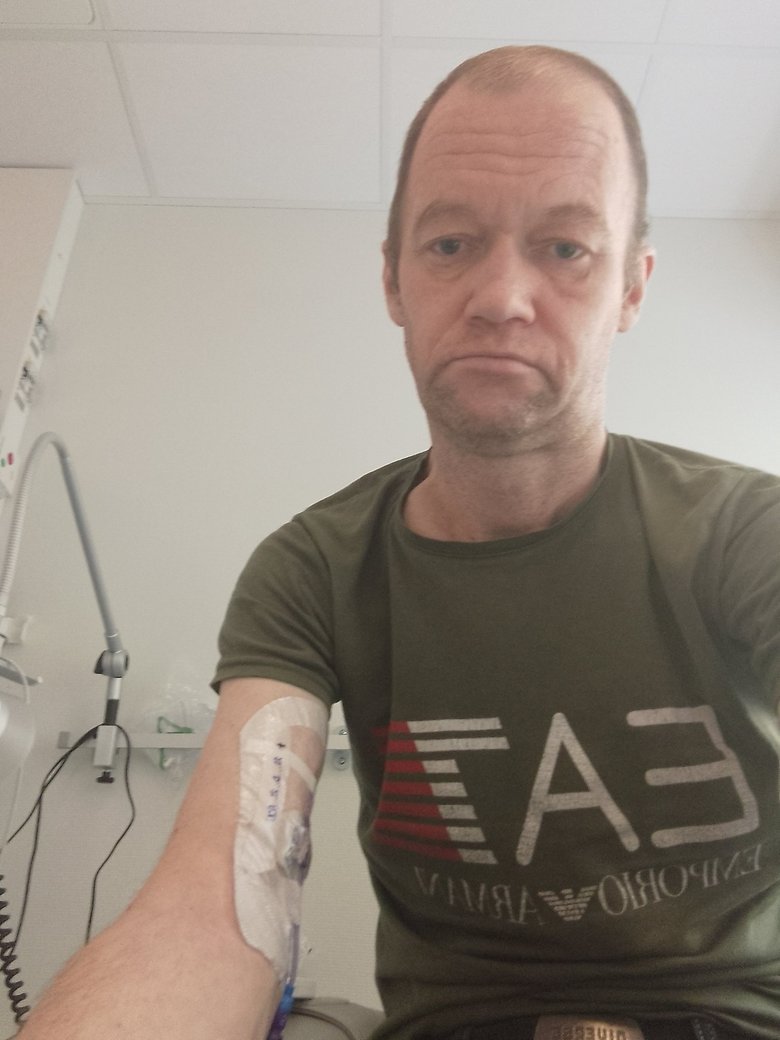

Recently, Censor.NET has begun documenting and reporting on violations of the rights of service members and veterans. The newsroom has been receiving letters with personal stories behind which lie broken lives and systemic problems. Among those who wrote to us is Oleksandr Poliarus, a reserve captain who was discharged from the Armed Forces of Ukraine on health grounds because he has cancer. For nearly three years now, he has been forced to undergo treatment for melanoma in Norway because no free treatment could be found for him in Ukraine.

"I have a question for the state I served for 14 years: why did everything I was promised turn out to be untrue?" Oleksandr explains in a phone conversation, describing why he decided to reach out. I did not receive housing from the state, neither during my service nor after it, and I was not employed after my discharge. And that is not even the worst part. They refused to treat me free of charge and handed me a bill for several hundred thousand hryvnias. And now the question: why does the government allocate money to treat, for example, AIDS, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, but not skin cancer? I will try to explain what I do not understand. The reasons I developed melanoma are a coincidence in time of the following factors: skin injury, exposure to the sun, and severe stress. In other words, conditions that are very common during military service and participation in combat. Whereas AIDS is contracted mostly in civilian life and is not connected in any way with service to the state. Here, AIDS is treated free of charge, fully funded by the state, while the state does not procure medicines to treat skin cancer. Why is there such an approach to choosing who gets to live and who does not? Who are the people who make that decision? Why did the state, after taking my service, make me a refugee in return by denying me treatment and therefore a chance to live? I would like to get answers.

- Let’s tell your story. You are a career serviceman. You chose this path even before the war with Russia. Why?

- I am the son of a serviceman, so I always wanted to be in the military. I completed compulsory military service, then graduated from Bogomolets National Medical University, and after that from the Ukrainian Military Medical Academy, and became a military doctor.

- Why did you choose this profession in particular? Was your father also a military doctor?

- No, my father was a warrant officer; he flew helicopters. But my grandfather’s neighbor, who was his peer, was a military doctor during World War II. He served in the 300th Regiment, which still exists in Desna. After talking to him, I became passionate about this profession. And I began my service there, in the medical battalion.

- Did he tell you about the war?

- More about service in the 1950s and 1960s, about what a military doctor actually is. During the war, he was the head of a medical post of an infantry battalion. It is a very bloody profession. That is probably why he did not like talking about it.

- What is your specialisation?

- A military dental surgeon. My first posting was to the 3rd Separate Special Forces Regiment in Kropyvnytskyi. I served as a doctor at the medical post, a dentist.

I served there for two years. Then I transferred to the medical company of the 128th Mountain Assault Brigade. And in 2013, I was transferred to the 17th Separate Tank Brigade and promoted to head of the brigade’s medical service. In general, dentists had not previously been appointed to that position. But by that time, the military medical system was already, to put it mildly, failing. For example, when I took up the post, the medical company was supposed to have 17 doctors on staff. But in reality, there were only three. And five days later, the war began.

- Did you know there would be a war? Were you warned, perhaps?

- No, I wasn't warned. But the first battles I took part in were an exact copy of the exercises I went through in 2012, when I was serving in the 128th Brigade. Back then, the ‘script’ was this: unknown troops from an unknown state cross the border into Ukraine and try to seize the border regions, and we repel them. We went through this one-for-one in 2014. So it was for that scenario that we were trained by Colonel General Hennadii Vorobiov, who at the time was commander of the Ground Forces (during the Revolution of Dignity, Vorobiov refused to deploy the army against activists, and later spent more than two years in the ATO zone – O.M.).

- You said you took part in combat. But you are a doctor. Was there a shortage of fighters?

- When it all started, we were severely understaffed. On top of that, we had no combat medics at all. And the 17th Tank Brigade I served in was a cadre brigade. That means that under the wartime table of organization, it should have about 4,000 service members, but at that time, there were roughly 425. That is normal for a cadre brigade. There was only the command cadre, so the unit could be rapidly expanded if needed. We had weapons. We were supposed to receive personnel and carry out missions. But for the time being, we were split into two parts. One half was formed into a rifle battalion. I became its chief medical officer. To put it in perspective: companies were commanded by colonels, platoons by majors, and the riflemen were captains and senior lieutenants. We had very few enlisted soldiers. The other half of the officers stayed with the brigade and, by October, expanded it to the required 4,000 service members.

- Where were you located?

- At first, on the second and third lines in the Kharkiv region, in the Barvinkove area. Then the Kulchytskyi National Guard Battalion took the first checkpoint near Sloviansk. In the summer, they were defeated and driven off the position. We were sent there, 54 men. We retook that checkpoint. The 95th Brigade helped us, by the way. That is where my first combat took place.

- What stands out from that period? And what did you think about Russia at the time?

- I knew much earlier that we would end up fighting Russia, back in 1997, when I began my compulsory military service. That was when the fleet was finally divided: we received only support vessels, while all combat ships went to the Russian Federation. We also allowed their contingent to remain in Crimea. Even then, I understood they would try to seize us. However, most of the servicemen I served with did not believe it. They thought it would be something like an Anschluss: we would simply become the Russian army, meaning our politicians would strike a deal that would effectively turn us into it. Most of them were not against that, but later they became Heroes of Ukraine. It is just that in those days the state, in effect, kept the army on a shoestring. People were very dissatisfied because of low pay. Meanwhile, Russians, on the contrary, kept getting pay raises. For example, when the war began, I, the brigade’s chief medical officer, was earning 5,300 hryvnias. A Russian in the same position back home, converted from rubles, was earning more than 20,000 hryvnias.

And when the war began, we actually experienced a strong sense of uplift. In the units where I served, we lived through the fall of both Sloviansk and Debaltseve. But there was an understanding: we could do something; we were not worse than the Russians.

- How long did you fight in the ATO?

- I took part in combat directly for about three months. Overall, I spent five months in the ATO.

- You were a rifleman. But you also had to provide medical aid, right?

- The nature of the fighting was very rarely infantry combat. Over those three months, I saw the enemy up close probably only twice. Most of the time it was something like "artillery duels." Yes, I provided medical aid. We took very heavy incoming fire several times.

I was with the personnel on the positions and, in practice, performed the duties of a combat medic. Although I was the head of the brigade’s medical service, my deputy remained on site and was forming the medical company.

Let me tell you about one incident. Our company commander, my subordinate, was at one checkpoint. I was at the second. And there was no one at the third. I went there and delivered medical supplies. There was a veterinary feldsher from the infantry there. I asked him, "Will you be a combat medic?" He agreed. When I arrived the next morning, he threw that medic’s bag at me. It turned out they had wounded overnight, and he got scared. You know, this happens very often in war. That is why I tried to stay on the positions. Because when people know they will get help, they perform well in combat. When that is not there, panic sets in.

- How did you learn about your diagnosis?

- While I was still in the ATO, I realized it could be something like melanoma, because I badly tore a mole on my back. We had positions where we were constantly exposed to the sun. When I got home at the end of October during a rotation, I went to the oncology center at the brigade’s permanent deployment location during the very first week. That is where I was diagnosed and underwent my first surgery.

- What stage was it?

- Zero. I simply detected the disease very early. I referred myself to the hospital because I was the chief medical officer. But in the end, in 2015, I was discharged from military service on health grounds and removed from the military register.

In 2017, a node appeared under my right armpit. I underwent surgery again - a muscle and the axillary lymph nodes were removed. I was treated not in a military hospital, but at the Kirovohrad Regional Oncology Dispensary. The doctors - Yurii Oleksiiovych Skorodum, Taras Mykhailovych Krama, and Ihor Edvardovych Liulia, essentially saved me; they did everything very professionally.

I completed rehabilitation, and nothing bothered me until 2022.

- We will talk next about what happened after that. I want to clarify something here: what procedure does a serviceman go through when cancer is detected? As far as I know, they are first treated in a military hospital and then, so to speak, move into civilian treatment. Did you run into any problems along that path?

- The only thing is that with this disease, the state should have discharged me immediately. But back then, the instruction was: do not discharge anyone for any reason. Even though keeping me in service made no sense.

There was also a misunderstanding: when I fell ill, as a serviceman of the 6th Army Corps, I was supposed to go to the Odesa Military Hospital. I filed a request. It turned out they do not perform the kind of surgery I needed. So I immediately informed my commander that I was being admitted to the Kryvyi Rih oncology center at my place of residence. Permission was granted. I was admitted. I underwent surgery. And then I went to the Odesa hospital for the military medical commission. The head of the department and the hospital’s then commander decided they would not process the chief medical officer’s medical discharge and redirected me to the Kyiv military hospital. Although they were supposed to decide it, they did not want to take responsibility. As a result, I simply traveled around Ukraine, I went to Kyiv as well.

- Am I right in understanding that the main problem along this path for a serviceman with such a disease is that precious time is lost?

- It all depends on the chief medical officer. In my case, the issue was resolved quickly because I was the chief medical officer. And chief medical officers can be very different. But you have to go to him. As a rule, you end up spending a lot of nerves "pushing through" decisions with the command. It is hard work, and not everyone wants to deal with it. But that is all part of the chief medical officer’s job.

For example, I first found out exactly where such an operation is performed. If a military hospital had done it, I would have gone there. But I learned they do not do it there, so I immediately chose a civilian facility and went there. To repeat, it was resolved quickly for me because I was the chief medical officer, and I approached a higher-level supervisor directly, the corps chief medical officer. But what if it were, for example, a lieutenant, a platoon commander? He would come to the chief medical officer, and he would not be there. Then it would be exactly as you said, time would be lost. And you cannot wait.

For example, in the French army, the head of the medical service is not subordinate to the unit commander. In the German army, too. I am in Norway now, and it is the same here. The chief medical officer is a specialist who stands alongside the commander, helps him, but does not carry out his orders, which sometimes, to put it mildly, can be strange for him.

So why were there no doctors in the medical companies either in 2014 or in 2022? Because the chief medical officer was subordinate to an infantry or tank commander. Many people cannot take this and simply leave. And no one wants to take these positions anymore. Only people like me who have served since their compulsory service stay, they are used to this style of command. And a person who has graduated from medical university comes in, looks at all this, and at the first opportunity "gets out of here."

- When you were discharged, was the disease linked to the defense of the homeland, or only to military service?

- It was linked to military service. For it to be linked to the defense of the homeland, I, as the chief medical officer, would have had to file a report on myself back during the ATO stating that I had injured that mole. But I did not do that. I had other things on my mind, I was thinking about something completely different. I had wounded personnel and other tasks. So I did not pay attention to it. And it cannot be processed retroactively.

- There is a difference there, including in payments.

- I received not a little over two hundred thousand, but eighty thousand.

- And were your surgeries free of charge?

- Yes. Both the first and second times.

- You wrote that there was a third surgery in 2022. What kind of surgery was it?

- The problems actually started back in 2021. But I did not notice them right away. At the time, I was working a very stressful job, I was the head of the medical service at a prison. When the full-scale war began, I wanted to return to service. But I felt unwell, so I went to undergo a medical examination. During an ultrasound, they saw that I had a metastatic growth on my intestine the size of a man’s fist. The entire small intestine was essentially "entangled." In April 2022, I underwent surgery at the Kropyvnytskyi oncology center, again, everything was done very well and free of charge.

But there is one important point. If I were a Norwegian citizen, they would not have operated on me here. In such cases, they provide drug therapy instead. In Ukraine, there are no free medications of this kind, and they are very expensive. So I was operated on, and because those drugs were not available, metastases began to reappear almost immediately. In other words, the surgery did not save me. But this is, in principle, characteristic both of melanoma and of such extensive involvement as in my case, since virtually the entire intestine was affected. It was physically impossible to remove everything. So the growths returned very quickly: on the skin, internally, and in the head. One of the metastases began to block my esophagus and breathing. That was when the hospital staff began urging me: go abroad as a refugee, treatment there would be free. At first, while I was feeling more or less okay, I rejected the idea. But when my condition deteriorated severely and I realized I was close to dying, I agreed. When I arrived in Norway, they initially wanted to perform a tracheostomy right away, to cut into my neck so I could breathe. However, they reconsidered and instead began administering the medications available here, and the tumor started to shrink. I am not in remission yet. There are many metastases, but they are not growing.

That means I would not even have needed such a traumatic surgery if those drugs had been available. I would have taken them, and the metastases would have regressed. You know, what angers me most is that this situation turned me into a refugee. I served this country, and I was told: if you want treatment, go abroad — it is free there. We will not do it here.

- Who suggested that you go abroad?

- The treating doctors, those who were monitoring me. After the surgery, I was transferred to the chemotherapy department, where they told me directly: there are no free medications. There is an option to go abroad.

- So the state gave you the opportunity to go abroad?

- I left with the help of "Medevac." As I later learned, it is a murky structure, seemingly neither state nor private; it is unclear. Everything there is closed. But they have channels for getting people abroad. This was offered to me by my treating oncologist-chemotherapist. He filed the request. And by the time I was leaving, Norway already knew that I was coming specifically for treatment. They even told me at the border which city I would be in. Here, ordinary refugees are sent to a camp, but I was sent straight to an inpatient facility for treatment. That is how the mechanism works.

- How were you transported?

- I got to Lviv on my own. From there, a Czech ambulance picked me up. They took me to Poland, and from Gdansk we flew — via Oslo, and then here. We crossed the border with virtually no checks. Our side did not look at anything at all; the Poles took a quick look and that was it. I do not even have a foreign passport, by the way. I never got one on principle. And now I have been here for almost three years. I feel better, but I have not recovered.

- What do the doctors say?

- Nothing. Melanoma is a disease that cannot be predicted. It can subside on its own, although that happens very rarely. And even good treatment may not help.

In 2023, I had a period when the disease progressed at lightning speed, literally week by week, especially after the surgery. I barely remember that time, my memory was even impaired.

- You also told us that you have been in Norway all these years without your family. That is hard, right?

- Yes. But we have an apartment. My wife works. She did not want to become a refugee.

She has a сategory III disability and has had diabetes for a long time. We have to live apart, but I hope it is temporary. She traveled with me to every garrison. And now, once again, service will not let go.

- And you have a child...

- I left when he was 14, and now he is 17. We talk on the phone. That at least helps a little in this situation.

- I assume you follow what is happening in Ukraine. What do you think about it?

- It is hard, but predictable. Do you know why I stayed in the military even though, before the war, it was very difficult and poor service? Because I knew we would have to fight Russia. And that is what happened. So I foresaw what is happening now. We have to get through it.

- And what do people in Norway say about our war?

- Norway is a NATO member. Their generals understand very well what is happening. They are genuinely surprised when some "NATO" generals start saying that we are fighting the war the wrong way. They ask: were you in their place? You have no idea what this is like. This is a sober assessment of the situation, and I would say it works in our favor.

Their armed forces are small: one infantry brigade, a strong navy for a country of their size, but a limited infantry component. There is a clear understanding here that if we fall, they will be next. And this is understood not only at the level of society, but also at the level of government.

- Given that you are a doctor and have cancer yourself, I want to ask how a person can independently understand that something is wrong with their body. Oncologists stress that service members face higher risks because of the conditions they operate in, carcinogens, constant stress, and so on. Cancer is a disease that often does not cause pain, at the early stages. And military personnel do not have the opportunity to undergo regular check-ups. What symptoms should people pay attention to so as not to miss cancer?

- In the case of melanoma, it is relatively simple, you need to monitor moles. If a mole is injured, it can look as if another one is growing on top of it, meaning its shape changes. Redness appears around it, and under certain lighting, it can look as if it has been sprinkled with glitter. In other words, it changes and no longer looks like a normal mole.

Lymph nodes are a separate issue. They are affected in cancer. Any metastasis passes through them, and they become inflamed. If there is persistent inflammation of the lymph nodes, that is already a warning sign that you need to get checked.

Overall, this should be the responsibility of the chief medical officer. This includes conducting educational work among personnel. Shit box tells people how they should love the homeland, but a doctor should be going around and explaining what signs they need to pay attention to. This kind of basic medical education should be ongoing.

- The official websites of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Defense do not provide detailed guidance on what a serviceman should do in case of suspected or diagnosed cancer. It is true that the Ministry for Veterans Affairs has an entire separate section titled "Treatment of oncological diseases." But that concerns a specific category of service members who are no longer in service. What about those on active duty? Is the state falling short on this issue?

- Very much so. If we look at documentation from before the war, for example, the Russians had dedicated websites. You would go there and it clearly said: "For chief medical officers." It was broken down by sections, with step-by-step instructions on what to do in specific cases.

We still do not have anything like that. The algorithm you are talking about, what to do step by step, has not been developed. If a serviceman suspects something, the law says he must turn to the chief medical officer. And the chief medical officer should already know what to do and guide him further. But the reality now is that battalion chief medical officers are extremely overloaded. Often, they do not match their professional role. And that is where all the troubles begin. They may not even pay attention to a serviceman’s complaints, assuming he simply does not want to go on duty or deploy on a mission. In other words, they may just not listen.

- There is another problem: the military medical commission does not have an oncologist on a permanent basis who can diagnose the disease. What should be done about that?

- A serviceman can seek care, as a civilian, at any oncology center. The system is in place. After the examination, they will establish the actual diagnosis fairly quickly. And with that diagnosis, you should go to the military medical commission. Normally, the head of the commission, based on tests and objective data, should suspect an oncological disease and refer the person to the appropriate specialist. The Armed Forces currently do not have a separate oncology service.

- Unfortunately, cancer is widespread today. I watched an interview with oncological surgeon Andrii Beznosenko, and he predicts that because of the war, including the carcinogens and stress I mentioned, as well as environmental factors, the biggest surge in cancer cases will occur around 2030. What do you think about this?

- Look, even before the war, I had large moles. Some of them I tore off during service and threw away, in particular, one was literally worn down by my belt, and another one fell off on its own at a training ground. I later got checked, and everything was fine. But during the war, I injured a mole for the first time and it turned into melanoma. Why did that happen? Because of severe stress. If it had not been for that, everything would have been fine. So you are right to note that the number of cancer cases will increase. This issue needs to be addressed at the state level. Now, corps have been created. The heads of medical services there must be qualified professionals, not people appointed at random. Do you know the difference between today’s appointments and those made during World War II? In some respects, the Soviet system was quite "alive." Today, if a unit commander happens to know a particular chief medical officer, that is who gets appointed. Back then, doctors were selected from hospitals. That is how it should be. In other words, a corps chief medical officer should be appointed by the head of the Armed Forces’ medical service. But that service has been dismantled and has not been restored.

- Was that before the war or already during it?

- It happened when, in the 2000s, the military and hospital branches were separated. In Soviet times, a doctor would graduate from the academy, go into the military, then advance and eventually move to work at a hospital. But from the 2000s onward, graduates went straight into civilian medical facilities. And whoever could be recruited locally was taken into the military medical branch, although they often later left.

In the 128th Brigade, the situation with doctors was relatively good because the medical company commander was experienced and respected, and could put infantry commanders in their place. The team held together under his "umbrella." Without that kind of authority in a brigade or battalion, there were not enough doctors.

Right now, they are simply filling positions. I personally know doctors who came from the civilian sector into the medical group of a mechanized brigade and ended up under enormous stress, something like shock and panic. Because in the military, you are not allowed to just be a doctor. You are expected to be an airborne trooper, an infantryman, an office manager, and there is no time left for treating patients. Because there is no one who demands medical work from you. But there are people who insist that the paperwork be in order, that the live-fire training be logged, and so on. As a result, the chief medical officer is buried in all kinds of paperwork and military training requirements. There is no time for anything else. A sergeant comes in and says, "Something is wrong here." The chief medical officer will look at him and, at best, tell him where to go and help him; at worst, he will snap back, "Don’t try to dodge duty!" The chief medical officer is often under pressure from above. When the war began, I was demanded to repair the toilet in the medical company. Or when I needed to train personnel, the brigade commander gave me a task: "I want to see what the medical company looks like in the field." I explained: "That is 17 tents." The reply was: "Then set them up." And instead of training people, I was looking for someone to set up those tents, each of them weighed 400 kilograms, and my medical company was made up entirely of women. So I was doing the wrong things instead of what was needed. In all my years of service, I never saw any support for the medical service. The situation now is identical.

Olha Moskaliuk, Censor.NET

Photos provided by Oleksandr Poliarus

P.S. Censor.NET has sent a request to the Medical Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine asking for data on cancer cases detected among service members, whether a link is established between the onset of the disease and military service, and information on government programs that provide treatment for such servicemen.