Wind of love and Defense Ministry: how unverified documents lead to undelivered supplies and scandals

The failure to deliver chemical warmers to Ukrainian service members has created a perfect opportunity to talk about why this happens. There are several reasons for it.

First, a brief outline of what happened: last year, the State Operator for Non-Lethal Acquisition (DOT) contracted 600,000 sets of chemical warmers out of the 1.1 million needed. However, only 300,000 from one supplier actually arrived at warehouses. The second supplier, Private Rear Operator LLC, delivered just 24,000. And says it will bring another 75,000 this week.

At the same time, the supplier drove the price for these warmers down so sharply (because the latest procurement price sets the indicative cost) that no one else bid in the most recent tender, and it won the right to supply another 500,000 sets of chemical warmers.

Unfortunately, tenders use the price-only criterion. Accordingly, whoever offers the lower price wins.

The logic is clear, but a positive outcome is not guaranteed. To recap, in 2024, Farminco-Nord drove down the price for a winter jacket in the same way. It had the jackets made in Vietnam, where production is cheaper, missed the deadline, and when the jackets arrived, they were deemed unfit for use.

But this was a shortfall of 75,000 jackets, so at the request of the Logistics Forces Command, the seizure was lifted from those same infamous Reznikov jackets, which also did not meet technical specifications, but had already been accepted and were sitting in warehouses, and they were issued to troops.

This greatly pleased the supplier, because at this point, the only evidence of the poor quality of its product is a video in Censor.NET’s blog, and it was very eager to get that piece taken down.

The second case involves those same Mindich's body armor vests. To recap, two unknown companies, with no production base and no experience in supplies, were able to pass the qualification thanks to footnotes to the qualification criteria.

The companies also drove the price of a body armor vest down to 21,000, but did not deliver a single vest in the first, second, or fourth batch. The vests themselves were later found, after live-fire testing, not to meet the product’s technical requirements.

Now to the third episode, the chemical warmers. There are no warmers, yet the price has been driven down from 26 hryvnias to 18, and then to 17.40.

Now for problem number 2.

After the price is lowered to a certain level, the agency uses it as the indicative cost for subsequent tenders. As a result, either one company monopolizes the market, or other companies are forced to supply at the lowest price, one that does not match their cost calculations.

This, of course, makes it possible to report savings when signing a contract, but in no way guarantees that it will be fulfilled.

And now we move to problem number three: how, exactly, do we verify the supplier?

To allow a company to take part in a tender, the law provides for four qualification criteria:

- availability of workers;

- availability of material and technical resources;

- availability of similar experience;

- financial capacity.

At its own discretion, the contracting authority may apply one or several of these criteria, which significantly shape the bidder landscape. At the very least, the absence of a requirement for a material and technical base already allows intermediaries or importers to participate.

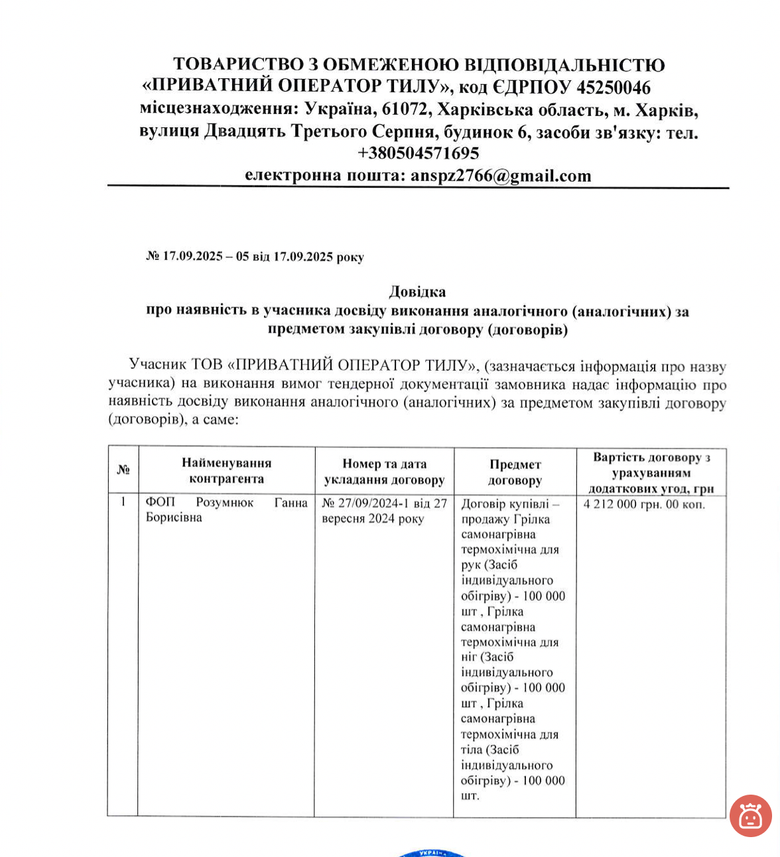

In the tender to procure chemical warmers, only two criteria were applied: financial capacity and relevant experience.

The company submitted a statement showing it had a similar contract with an individual entrepreneur.

It is hard to see how a document like this can guarantee a company’s ability to deliver anything at all. Yet it is considered sufficient for the Defense Ministry.

Of course, companies that have been in this market for decades have an advantage, because they can submit contracts with the Defense Ministry and service acceptance acts. That option is not available to a new company.

But in cases like this, there should be a different approach to vetting newcomers, not just a manufacturer’s guarantee letter and a self-issued statement that "we’re good." Because, once again, Mindich’s body armor vests never arrived.

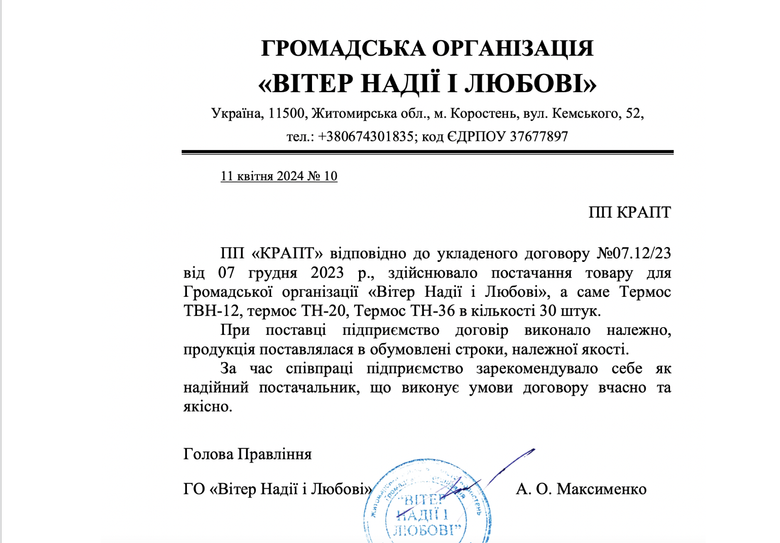

In 2024, in tenders to procure thermoses, DOT applied only two qualification criteria: prior experience and financial capacity. As proof of prior experience, PP "KRAPT" submitted the following document:

It is hard to say how much faith and love there is in the wind. But later it emerged that PP "KRAPT" is mentioned in criminal proceedings over the supply of 36 unfit aviation fuel tanks to a military unit in the Lviv region for 15 million hryvnias.

In August 2024, Lviv’s Halytskyi District Court imposed a preventive measure on the company’s director and seized the company’s property.

Whether the company delivered the thermoses after that is unknown. But clearly, documents like these cannot serve as proof of capacity.

In general, it has been a long time since discussing non-price criteria in procurement and spelling out how they should be applied. But clearly, that will be a long road.

So, to start with, it would be enough to introduce basic checks of the documents submitted for tenders.

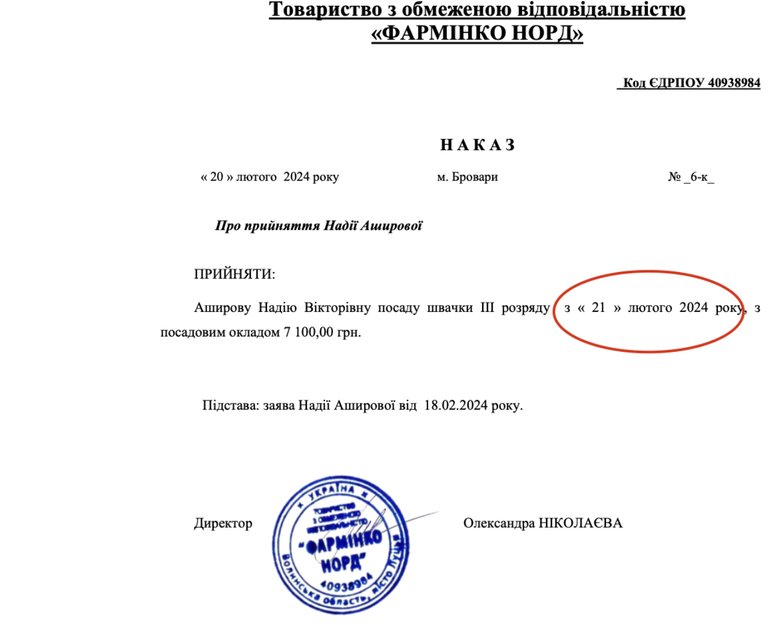

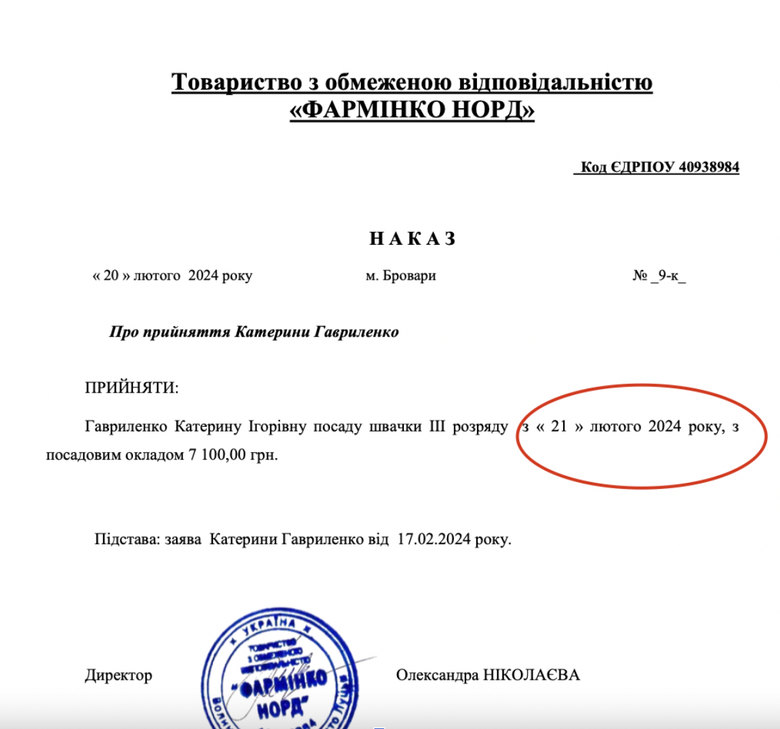

So that there is no repeat of what happened with Farminco-Nord, which never fulfilled the jacket order, when it turned out that all workers had been hired on the same day, shortly before the tender.

Or as in the story of Mindich’s body armor vests, when a certificate of conformity was produced by a company that had nothing to do with participation in the tender.

Of course, there is always the option of saying, "we simply don’t have the authority," but then welcome to a hell of scandals and curses.

Otherwise, this is a path toward chronic delivery failures.

Tetiana Nikolaienko, Censor. NET