Era of Ukrainian drones that reshaped war. How UAVs evolved on battlefield

Drone Industry

On December 15, details emerged of a new brazen operation by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) that can be ranked alongside the now-legendary "Spiderweb". This time, using Sub Sea Baby underwater drones, the SBU blew up an enemy Varshavyanka-class submarine in the port of Novorossiysk, estimated to be worth $400 million. It was the first time anything like this had happened in history.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukraine entered the war with a fairly limited lineup of UAVs. They were mostly reconnaissance drones from the ATO/JFO period and Chinese-made Mavic drones modified to meet the military’s needs. Domestic drone production was limited to about a dozen companies, and no one even dreamed of creating the Unmanned Systems Forces — a separate service branch within the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

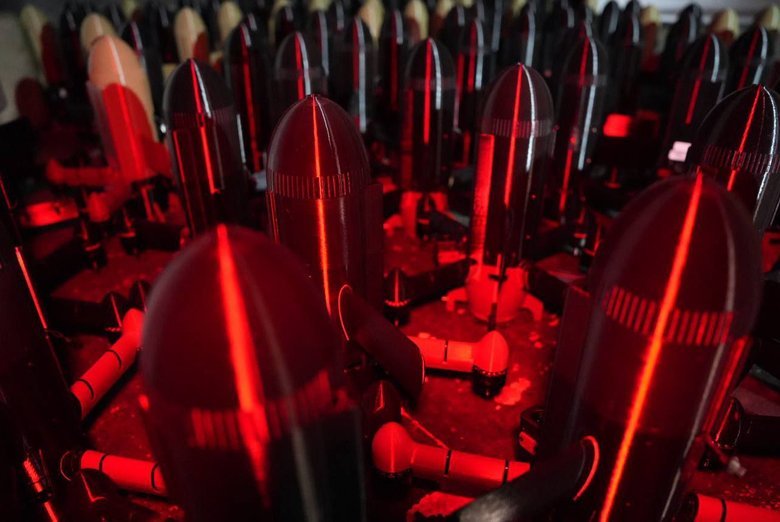

Today, UAVs account for about 60% of all hits on enemy targets, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Oleksandr Syrskyi says. In 2025, the annual output of different types of drones rose to 4 million units, more than all NATO countries combined produce.

"Drones truly led the revolution in defense technology in 2022. Unmanned aerial vehicles have a relatively low barrier to entry, which drew early talent into the sector and delivered a major boost in Ukraine in a relatively short time. That turned drones into a commodity. Today, building drones is a matter of production optimization and supply-chain efficiency. This is a space for private capital and experienced industrial players," says Anton Verkhovodov, a partner at the D3 investment fund, which invests in defense startups.

At the same time, Denys Chumachenko, Chief Technology Officer (СTO) of DEVIRO, a company that stood at the origins of Ukraine’s domestic drone industry, says it is not entirely accurate to call the current progress in unmanned technologies a revolution.

"The revolution was the first leap, when Ukrainian manufacturers, scientists, and engineers realized these technologies could be scaled and implemented to produce strike capabilities. All these leaps are possible when there is motivation, a philosophy, and an idea. Right now, the idea is simple: if we don’t do it, we won’t survive," he stresses.

"If you compare the war in 2022 with the war in 2023, 2024, and 2025, these are completely different approaches, different principles, and different outcomes. When we talk about technology, we mean tools that make it possible to save lives on the battlefield, our soldiers’ lives, and civilians’ lives in the rear," adds Roman Kostenko, secretary of the parliamentary committee on national security, defense, and intelligence, and an ATO veteran.

As part of the "Drone Industry" project, Censor.NET examined how unmanned technologies have changed over the course of the full-scale war, what is currently in focus for the military and manufacturers, and what industry trends could emerge next year.

The front line tells manufacturers what it needs, not the other way around

Viktoriia Honcharuk, head of the defense technology department at the Snake Island Institute and a paramedic with the Hospitallers, recalls that during the early phases of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainian troops used almost all drones in the same configuration in which they were received.

"Speed mattered more than optimization, and there was no time to adapt systems to the realities of the battlefield. But almost immediately it became clear that many platforms could not be used effectively in their initial configuration. To survive under electronic warfare, given the terrain, weather, and the enemy’s tactics, the systems had to be modified," she explains.

According to Honcharuk, at first these adaptations were relatively minor: swapping out the video transmitter, replacing antennas, tuning power systems, modifying firmware, or changing communications links. In other cases, the changes were far more substantial, affecting navigation, control logic, payload integration, or the platform’s survivability.

"Over time, it became the rule rather than the exception that drones and other unmanned systems had to be modified right near the front line to make them useful," says the head of the defense technology department at the Snake Island Institute.

This necessity drove an organic transformation within the army, Viktoriia Honcharuk notes. Most platoons or units that relied on technology began setting up improvised workshops of their own, where troops and engineers modified, repaired, and reconfigured systems under combat conditions. These workshops became critical innovation hubs, tightly linked to real-world combat feedback.

"The next step was inevitable. Instead of endlessly adapting off-the-shelf systems, Ukrainian units began developing their own solutions from scratch. In some cases, that meant specialized software or communications layers; in others, fully indigenous drones, interceptor UAVs, and uncrewed ground vehicles designed specifically for the conditions of this war," says the Hospitallers paramedic.

Ultimately, the process led to the emergence of military workshops within frontline units, small, agile teams that now design, test, and field their own technologies.

"These workshops close the loop between the operator, the engineer, and the battlefield in real time, cutting innovation deployment timelines from years to weeks," Viktoriia Honcharuk notes.

Denys Chumachenko, CTO of DEVIRO, says there was an enormous demand for UAVs at the front, both before and after the full-scale invasion. People did not think too much about performance, quality, or price, because even a subpar drone was better than no drone at all.

"Now we’re seeing a market trend. Users have become more demanding. They’ve seen global counterparts and products from Ukraine’s top companies, so they’ve started setting tougher requirements. If a manufacturer doesn’t make quality products, doesn’t produce them quickly, and can’t keep pricing competitive, no one will buy anything from that manufacturer. These days, it’s the front line that tells the manufacturer what it needs, not the other way around," he explains.

Interceptor drones, UGVs, and fiber-optic control: 2025 trends

If 2022 can be условно described as the "year of FPV", when mass production and battlefield use took off, then 2025 is the year of three key areas:

- the development of air defense, specifically the integration of interceptor drones into it;

- broader use of unmanned ground vehicles that have met logistics and evacuation needs;

- the growing adoption of fiber-optic drones as an advanced strike capability.

Interceptors

"Faced with the persistent threat posed by Shahed-type drones, interceptors have evolved from experimental tools into another layer of the broader air defense system. Their development is continuous: speed, navigation, autonomy, and cost-efficiency are all improving," says Viktoriia Honcharuk.

She notes that Shaheds are also evolving to counter interceptors: flight profiles, navigation, electronic protection, and mass-launch tactics are changing as well.

"This has created a constant technological duel, where air defense has to adapt week by week rather than rely on static solutions," Honcharuk explains.

DEVIRO adds that countering UAVs with interceptors has spurred the development of solutions designed to evade interceptors — a kind of "anti-anti-drone."

For example, the company equips its systems with a technology called "Snitch" — optical sensors that use AI to process the imagery around them and decide on an evasive maneuver when a threat is detected. The maneuver algorithm is programmed based on the experience of servicemembers who intercept Russian drones. If the maneuver fails, the platform turns back, as it cannot continue the attack.

"We must build interceptors, use them, and train personnel so they can employ them. The infantryman remains the gravitational center of the war. And when his family is in Kyiv or any other rear-area city, he has to be confident that his loved ones will be safe. That is why Shahed interceptors are a crucial area that must be developed and brought as close to ideal as possible, to be effective against this type of weapon the enemy uses," says Mykyta Nadtochii, deputy commander of the 1st Azov Corps of the National Guard of Ukraine.

According to Denys Chumachenko, CTO of DEVIRO, interceptors will continue to evolve.

"We’ve more or less covered the close-in zone, the solution works. But in modern interception doctrine, there is a close, medium, and long-range engagement zone. "So in the near term, next year, I think they’ll try to work the long-range layer to take some pressure off the close-in one," he says.

UGVs

The use of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) has already moved from trials to systematic employment, especially for logistics, resupply, and evacuating wounded from the combat zone, says Viktoriia Honcharuk, head of the defense technology department at the Snake Island Institute and a paramedic with the Hospitallers.

"Importantly, even enemy forces have begun using UGVs for logistics, showing that ground autonomy has crossed a practical threshold. Several Ukrainian brigades have already demonstrated repeated, organized use of UGVs, marking their shift from experimental platforms to operational tools," she says.

Read more: UGV is expensive hardware, but compared to human life, it costs pennies

At the same time, unmanned ground vehicles have not yet fully realized their potential, Denys Chumachenko notes.

"There aren’t as many UGVs as, say, FPVs or the different types of fixed-wing reconnaissance drones. That’s why robotic ground systems need to scale up and they’ll be a major trend," he stresses.

UGVs primarily cover two needs: logistics and evacuation. However, they have already started being used as combat modules as well.

"It’s not as effective as we’d like so far. But this idea has a right to exist. I’ve seen videos of the enemy preparing to use different types of UGVs to carry out so-called micro-mechanized assaults. In other words, one UGV rolls in and lays smoke, followed by platforms carrying combat modules, including machine guns. Will it be useful on the battlefield? We’ll have to see. How does it work right now? A column of vehicles moves out, regardless of type, whether tanks, APCs, or IFVs. It gets spotted and taken apart by the same FPVs. The same will happen here. It might work as a maneuver, but it probably won’t change the course of the war," says Mykyta Nadtochii.

In his view, UGVs should be developed primarily for logistics and evacuation, with greater mobility, speed, thermal protection, payload capacity, and an increased operating range. The latter depends on reliable communications. And that, Denys Chumachenko notes, is expensive.

Fibre optics

The development of uncrewed ground systems is tied to the expansion of the "kill zone", an area where nearly any target can be engaged. Previously, it ranged from 500 m to 2 km, but now it is 5 km, and in some areas of the front line – up to 7-10 km. The military is already talking about 20-25 km as a realistic prospect. Fire control in the kill zone is primarily provided by fibre optic drones.

"When we talk about the forward edge, fiber-optic drones have now become the primary strike platform. And the Russians’ are currently better than ours. That’s due to direct supplies of better components and the fiber itself from China, and the ability to scale production at state-owned enterprises. This expands the so-called kill zone. That is where technologies that can replace humans on the battlefield come into play, driving the development of unmanned ground vehicles. Today, logistical sustainment and evacuation are carried out using UGVs — another strong indicator of how the theater of war has changed in 2025," says Yurii Fedorenko, commander of the 429th Separate Unmanned Systems Regiment "Achilles".

Fiber optics is what lets you peek into any gap and stop any mechanized assault, because analog links are vulnerable to electronic warfare, adds Mykyta Nadtochii, deputy commander of the 1st Azov Corps of the National Guard of Ukraine.

"Until you take out EW with fiber optics, all analog goes down. Fiber optics is effective and delivers results," he stresses.

Expectations and forecasts for 2026

Clearly, interceptors, UGVs, and fiber optics will remain in focus for both the military and manufacturers, as they have proven their effectiveness. First and foremost, their operating ranges will expand, which will inevitably affect employment tactics.

Read more: What drone synergy is and how it affects war

Viktoriia Honcharuk, head of the defense technology department at the Snake Island Institute and a paramedic with the Hospitallers, believes 2026 will be the year strike-capable UGVs are rolled out systematically.

"Although only a few units currently employ uncrewed ground systems in strike roles, 2026 is expected to bring broader, structured use across many units along the front. Strike UGVs allow explosives or firepower to be delivered into difficult conditions without putting personnel at risk. This helps offset manpower shortages while directly saving lives. The emphasis will shift to reliability and autonomy under electronic warfare, and to proper integration into combined-arms operations," she is convinced.

The second area to expect next year, Honcharuk says, is a reassessment of the cost per strike in aerial attacks.

"FPVs are now standard, low-cost attack systems. And they remain important. However, destroying large or hardened targets often requires dozens of FPVs, which drives up costs. In 2026, Ukraine is expected to rely more on reusable heavy bomber drones such as Vampire, Nemesis, and Heavy Shot. These platforms are reusable, carry heavier payloads, and significantly reduce the cost of an effective strike compared to mass FPV saturation," says the head of the defense technology department at the Snake Island Institute.

Unmanned technologies will also move toward greater automation, which DEVIRO CTO Denys Chumachenko says is critically important right now.

"Unfortunately, smart people are running out. And to be able to carry out missions, we need a higher level of automation. For example, interceptors should be able to autonomously get to the target area, rather than flying by visual landmarks. This has to be integrated into information-sharing systems. Automated target acquisition so the operator only has to click, and the system then performs final guidance. So I think automation will happen one way or another," he believes.

"In my view, the future is automation, for example, automation of command and control. Everyone has probably heard of drone swarms. In 2026, we may see one operator sitting at a remote console simply overseeing an area where hundreds of drones are airborne, automatically flying, scanning, detecting targets, and returning to recharge. This is already being worked on. And we could reach a point where these gray zones (meaning the kill zone - ed.) are fully automated. And people will simply need to supply weapons there," adds Roman Kostenko, secretary of the parliamentary committee on national security, defense, and intelligence, and an ATO veteran.

Mykyta Nadtochii, deputy commander of the 1st Azov Corps of the National Guard of Ukraine, expressed a similar view. He says AI-enabled drones that can autonomously detect, identify, and strike targets, as well as drone swarms, could become a reality as early as next year.